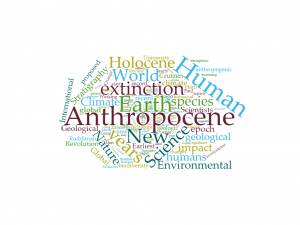

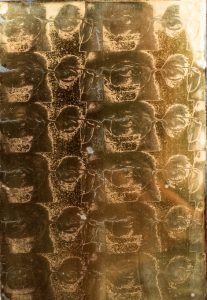

“Anthropocene Word Cloud from Wikipedia.” Notably, the words colonial, imperial, indigenous, violence, and their derivatives do not appear.

“It is hard for us to examine our connection with unbearable pasts with which we might reckon better, our implication in impossibly complex presents through which we might craft different modes of response, and our aspirations for different futures toward which we might shape different worlds-yet-to-come[.]” —Alexis Shotwell, Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times

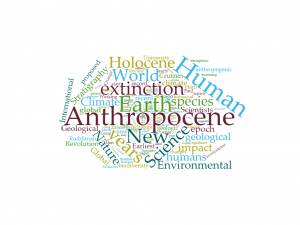

Anthropocene: A blanket term

Anglocene, Anthrobcene, Capitalocene, Cthulcene, Eurocene, Manthropocene, Misanthropocene, Neganthropocene, and Plantationocene: this is the current slate of monikers for the Anthropocene, a proposed geological epoch with historical debates over its start-date as deeply entrenched as those over its name. This ever-expanding catalogue of inspiring neologisms, however, suggests more than the schizoid nature of the Anthropocene and reveals more than simply an embryonic idea still in the process of being worked out, although its very existence is not unanimously acknowledged, as the surprise announcement of the Meghalayan Age by the International Union of Geological Sciences reveals [1].

The blur of proposed names for this new geological epoch is the symptom of a deeper unease that we have with the progenitur term “Anthropocene,” an unease that deepens with its disciplining, that is, in a Foucauldian vein, in the way this term is becoming sedimented and accepted as a disciplined body of knowledge [2]. Think, for instance, about the coalition of the Anthropocene Working Group, the task-force that determines the key parameters of this new epoch, a group that, as Oxford economist Kate Raworth shrewdly observes, is overwhelmingly made up of white, European men [3]. This raises the important question of who is the Anthropocene for? Who speaks for it? Who does it represent, and who does it erase? The question we must ask is this: In what ways is a certain structural violence, a colonial violence, smuggled in under the covers of this definition?

To think about this dark side of the Anthropocene requires attention to the erasure inherent in this definition of the anthropos (by its Greek roots, a white, universal, European subject). Recent work by Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin, among others, helps to shed light on the ontopolitics of this new epoch, as they rightly identify colonial violence as an inherent factor within the process of humans becoming a dominant force on the earth. Although Lewis and Maslin (2015) date this violence to the late fifteenth century in what they call the “New-Old World collision,” when Europeans arrived in the Americas, the long eighteenth century—the period that many consider to be the dawn of the Anthropocene, or at least the initialization of a new phase in its development [4]—continued to be a hotbed for settler violence twinned with destructive means of terraforming, particularly in North America. In what follows, I offer one particular eighteenth-century event—the British military’s bio-weaponization of smallpox against North American Indigenous peoples—as a touchstone for thinking about this structural violence, an event that might also serve as a metaphor for some of the dangers we continue to face in our conceptualization of the Anthropocene today. We can read this bio-weaponization forward into our own contemporary moment where the Anthropocene turns toward indigeneity as its model for resiliency while still problematically failing to account for the legacy and ongoing structural violence against Indigenous peoples.

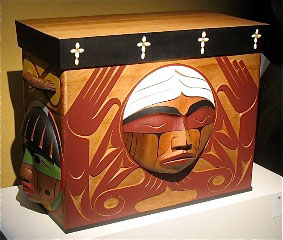

Blanket Stories: Seven Generations, Adawe, and Hearth (2013) by Marie Watt.

Eighteenth-Century Biowarfare

Letters and journals prove that high-ranking British military leaders during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) conspired to weaponize smallpox against North American Indigenous populations as a way of exterminating them and gaining access to their lands and resources [5]. In a letter (16 July 1763), just one of many that disclose this sentiment, British General Jeffery Amherst, commander-in-chief of the British Army in North America during the Seven Years’ War, writes to Colonel Henry Bouquet:

You will do well to try to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race. I should be very glad your scheme for hunting them down by dogs could take effect, but England is at too great a distance to think of that at present. [6]

Blankets were to be infected with smallpox and given as gifts to Indigenous groups, since the use of dogs would prove impractical. Moreover, the bioweaponized blankets were a far more insidious form of violence, and rise to match the colonial fears over the enmeshment of Indigenous bodies and the untamed landscape. Clearly, Amherst’s desired “Total Extirpation of those Indian Nations,” [7] as he elsewhere writes, was intimately bound up with the project of controlling the land [8]. In fact, the colonial biopolitical association of the wild Indigenous body with the land is poignantly captured in an anxious comment by Bouquet in a letter to Amherst (29 June 1763): “every Tree is become an Indian” [9]. The conflation of these bodies bears the scars of Lockean property theory, which conceptually underpinned colonial expansion and the violent treatment and dispossession of Indigenous peoples [10].

For Locke, the difference between merely living off the lands (hunting and fishing like animals do) and cultivating the lands in efforts of improvements is the difference in who has the right to claim ownership of that land. In his Two Treatises on Government, especially The Second Treatise, Locke writes: “As much land as a man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can use the product of, so much is his property. He by his labour does, as it were, enclose it from the common” [11]. Put otherwise, it is labour in the service of improvement that grants the right to the earth [12]. From a Lockean perspective, then, unimproved or cultivated lands used by Indigenous peoples were still part of the common, a wasted or missed opportunity for development. Indeed, the same language and colonial logic continues to be used, over two centuries later, in discussions about the Canadian tar sands. As Rick George, former president and CEO of Suncor, the Alberta-based energy company writes, “The most appealing feature of the oil sands was the fact that they were there to be taken” [13].

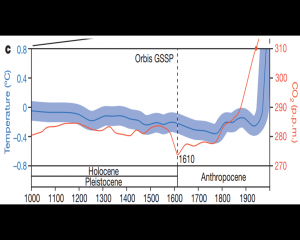

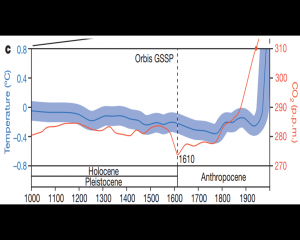

Yet British efforts at terraforming were simultaneously and intentionally a project of Indigenous genocide, as Amherst’s letters betray. Such an example dovetails with Lewis and Maslin’s “Orbis hypothesis,” their claim that “colonialism, global trade and coal brought about the Anthropocene” [14]. Indeed, their proposed date of 1610 for the onset of the Anthropocene, the Global Stratotype Section and Point [15] or specific date that marks a significant CO2/carbon decline (that they dub “The Orbis Spike”), is directly the result of drastic population decline due to war, enslavement and disease, with the Americas going from 54 million people in 1492 to only 6 million people by 1650 [16]. In short: less people, less carbon. Colonial violence thus registers itself in the carbon footprint of the Earth. The British efforts to bioweaponize smallpox against the Indigenous peoples in the eighteenth century complement Lewis and Maslin’s theory and furnishes it with a specific event to greater texturize this Anthropocene historiography.

“Orbis Spike” in Lewis and Maslin (2015).

Bearing the unbearable past in our impossibly complex present

But what does this specific case study in eighteenth-century British bioweaponization mean for us in the Anthropocene today? Anecdotally, it might remind us about the dangers that can lay await in the folds of a blanket or blanket term, a reminder to be weary of what is “gifted” by this ghostly anthropos, this new ungainly spectre haunting thought today [17]. The case study should also remind us of the biopolitics of controlling the Indigenous populations and their lands, and the violent means that these settler nations called Canada and the United States, or Turtle Island, have deployed since the eighteenth century. But more importantly, as the Anthropocene increasingly dominates scholarly discourse, such that we might speak of the “Anthropocene turn” in academe, the case of the smallpox-infested blankets helps reframe discussions of the Anthropocene that otherwise continue overwhelmingly to exclude Indigenous groups and considerations of colonial violence. We must consider more than the (white) anthropos and fossil fuels. For as Zoe Todd insightfully suggests, the Anthropocene discourse is a variation of “white public space,” that is a space that is not only predominantly made up of the white heteropatriarchy but also a space wherein “Indigenous ideas and experiences are appropriated, or obscured, by non-Indigenous practitioners” [18]. The Anthropocene needs decolonizing and indigenizing, though this move is not without wrinkles.

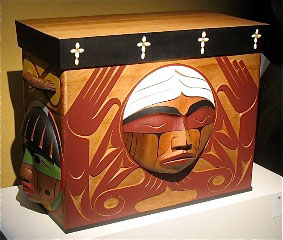

The Bentwood Box (2009) by Coast Salish artist Luke Marston.

One of the best examples of this is the simultaneous turn that is occurring alongside the Anthropocene: the “Indigenous Turn” in theory and politics, which on first glance appears inspired by governmental calls for reconciliation. However, while the “Anthropocene Turn” and the “Indigenous Turn” would benefit from greater turning toward each other, we have reason to be wary of the ways that indigeneity is currently being looked to as a new promissory radical model for ontology, which can be understood as a form of neoliberal governmentality’s delusory strategy for survival and self-replication rather than profound change, such as the indigenization of its internal structure. Indeed, as David Chandler and Julian Reid argue, the interest in new models of indigenous subjectivity is frequently marked by the rhetoric of resiliency. While this may initially seem like a celebration of indigeneity, Chandler and Reid argue that the real attraction to indigenous resiliency is for the way it might help Western cultures cope with how to live within the eco-crises of the Anthropocene: “While the modern subject is encouraged to ‘become indigenous,’ the attention to indigeneity . . . does not extend to the suffering and struggles of indigenous peoples who are held to have failed to become more-than-human exemplars of resilience” [19]. At the edge of extinction, Western culture hopes to learn how to survive. The “radical promise” of indigeneity as a new model for being in the world, Chandler and Reid continue,

is that a different world already exists in potentia and that moderns can choose to make it by learning to world in the ways indigenous peoples already do . . . Access to this alternate world is a question of ontology—of being differently—being in being rather than thinking, acting and world-making as if we were transcendent or possessive subjects. [20]

Now, in the Anthropocene, we no longer have the security in thinking of nature as something “over there,” as an object capable of being fully understood, and the collapse of the nature/culture divide. Now, the “indigenous are the anthropocene-alogists of nonmodern ontology: they can teach us how to see the nonhuman differently” [21]. If Indigenous subjectivity is now a resource to be mined, what becomes visible in this extraction process is the difference between attending to indigeneity and the actual suffering of indigenous peoples. We need to mind the gap between theory and practice. In the turn to indigeneity as the way to navigate the Anthropocene, what dangers are unknowingly accepted as gifts?

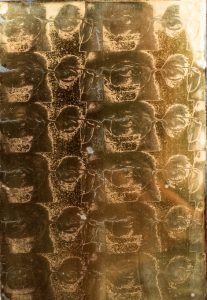

Harper Eyes (2014) by Métis scholar and artist Warren Cariou. The eyes belong to Stephen Harper, former Prime Minister of Canada, who passed major reforms for the oil industry during his tenure and who also infamously said, at the 2009 G20 meeting, that “Canada has no history of colonialism.”

Like those infected blankets in Amherst’s letters, we would do well to remember to ask what violence gets insidiously smuggled in under the white covers of the Anthropocene, which one might be tempted to call (if yet another neologism were allowed) “The White MANthropocene,” for the way it extends the legacy of this problematic figure, including the tendency of this discourse parasitically to see indigeneity as its new resilient ontopolitical host. Not unlike the eighteenth-century British view of North America as a waste to be mined, contemporary Western discourses including the Anthropocene commit an uncanny act of violence in the turn toward indigenous subjectivity as a new resource to be plundered. The Western question it seems, now as then, remains one of manipulation and self-preservation: How can we use indigenous subjects or knowledges to save ourselves, our ways of life, our institutions, and ultimately our world? We need to recognize, as Alexis Shotwell suggests, the “complex entanglement of practices and habits of ignorance, repression, and active disavowal that constitute an active settler process of not telling, not seeing, and not understanding the truth of the matter” [22]. This is especially true as we wade through a new cold white discourse that still largely ignores a decolonized approach.

Retrieving and bearing the anthropogenic ugliness of our eighteenth-century history, those disastrous events, such as the smallpox conspiracy that I have here discussed, will be an important strategy in how we write the history of the Anthropocene, a historiography that although it already includes the eighteenth century and grants a significant place to Britain in this narrative is nevertheless marked by blindspots. It is time to move past the now all too familiar citation of James Watt’s improved steam engine and the Industrial Revolution as the eighteenth century’s claim to the Anthropocene and consider the more furtive forms of anthropogenic violence from this period. Simultaneously, it is also important to recognize the ways in which these forms of violence remain with us today. To do this is to see colonialism, as Patrick Wolfe does, as “a structure rather than an event,” whereby colonial practices of the past grow to become the backbone of the present [23]. Indeed, the pressing task for the historiographies of the Anthropocene will be to consider the minor rather than molar, and increasingly to include in the stories that we tell about this epoch the shameful policies devised and violence committed in the projects and name of colonial terraforming. By insisting on these historiographies that foreground the “complicated, often ugly, and humbling,” to borrow a phrase by Anna Tsing [24], we might stop perpetuating the structural violence that has defined the Anthropocene.

Notes

[1] The IUGS announced in July 2018 that we are not in the Anthropocene; we are living in a late phase of the Holocene period that they call the Meghalayan Age, which began 4,250 years ago. It is defined by a catastrophic drought that destroyed ancient civilizations in Egypt, China, India, and the Middle East. As Mark Maslin and Simon Lewis write: “it seems like a small group of scientists [at the IUGS]—40 at most—have pulled off a strange coup to downplay humans’ impact on the environment.” Maslin, Mark, and Simon Lewis. “Anthropocene vs Meghalayan—Why Geologists are Fighting over whether Humans are a Force of Nature.” The Conversation, 8 Aug. 2018.

[2] Working groups, conferences, academic journals, courses, and programs are all examples of this disciplining.

[3] Raworth, Kate. “Must the Anthropocene be a Manthropocene?” The Guardian. 20 October 2014. Web.

[4] Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer initially proposed James Watt’s improved steam engine in 1784 and the Industrial Revolution as the starting point for the Anthropocene. Similarly, others take 1800 as the starting date, such as Steffen et al. (2011) and Zalasiewicz et al. (2011). Steffen, Will, Jacques Grinevald, Paul Crutzen, and John McNeill. “The Anthropocene: Conceptual and Historical Perspectives.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. A 369 (2011): 842-867. DOI: 10.1098/rsta.2010.0327. Zalasiewicz, Jan, Mark Williams, Richard Fortey, Alan Smith, Tiffany L. Barry, Angela L. Coe, Paul R. Bown, Peter F. Rawson, Andrew Gale, Philip Gibbard, F. John Gregory, Mark W. Hounslow, Andrew C. Kerr, Paul Pearson, Robert Knox, John Powell, Colin Waters, John Marshall, Michael Oates, and Philip Stone. “Stratigraphy of the Anthropocene.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of Lon. A 369 (2011): 1036-1055. DOI: 10.1098/rsta.2010.0315.

[5] Peter d’Errico’s archival research was key in finding proof of Britain’s smallpox plans and Amherst’s culpability. For a detailed account of the pertinent letters, see d’Errico, Peter. “Jeffery Amherst and Smallpox Blankets.” Web. 2017.

[6] Amherst to Bouquet, 16 July 1763, BL Add MSS 21634, f.323. See also The Journals of Jeffery Amherst, 1757-1763. Ed. Robert J. Andrews. Michigan State University Press, 2015. Vol. 15. 322.

[7] Amherst to Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of the Northern Indian Department. 9 July 1763. Amherst, Jeffrey. The Journals of Jeffery Amherst, 1757-1763. Ed. Robert J. Andrews. Michigan State University Press, 2015.

[8] This tension over the land plays out in another register today. Amherst is a figure still embarrassingly celebrated by Parks Canada today. The name of the Port-la-Joye-Fort Amherst National Historic Site in Prince Edward Island was recently challenged by Mi’kmaq elders and the Mi’kmaq Confederacy of P.E.I. Yet despite these calls for the national historic site to have Amherst’s name removed, Parks Canada decided to leave it and simply add a Mi’kmaq name: Skmaqn, which means “the waiting place.” Ironically, we still wait for reclamation.

[9] Colonel Henry Bouquet to General Amherst, 29 June 1763.

[10] Nick Allred’s contribution to this collection also attends to Locke’s theory of property, but it does not address the key role of labour in Lockean property theory and its relation to colonial violence. Katherine Binhammer’s contribution, drawing on Adam Smith rather than Locke, acknowledges the colonial violence that comes with the addiction to economic growth.

[11] Locke, John. Two Treatises of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration. Ed. Ian Shapiro. Yale University Press, 2003. §32; Two Treatises 113.

[12] Also in the Second Treatise, Locke grants that Indigenous hunters claim property over their goods, such as the deer they have killed (his example) because they have “bestowed [their] labour upon it” but does not extend to them a property claim of the land as, per his definition, no labour has been exerted (Second Treatise §30; Two Treatises 112).

[13] Helbig, Louis. Beautiful Destruction. Rocky Mountain Books, 2014, 57.

[14] Lewis, Simon, and Mark Maslin. “Defining the Anthropocene.” Nature 519 (12 March 2015), 177.

[15] GSSP is a Global Stratotype Section and Point, a specific date and primary marker (aka, “golden spike”) for any significant change in the Earth system.

[16] “The accompanying near-cessation of farming and reduction in fire use resulted in the regeneration of over 50 million hectares of forest, woody savanna and grassland” (Lewis and Maslin [2015] 175).

[17] J. R. McNeill claims the Anthropocene is the “specter . . . haunting academia” (117). Neill, J. R. “Introductory Remarks: The Anthropocene and the Eighteenth Century.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 49.2 (2016): 117-128.

[18] Todd, Zoe. “Indigenizing the Anthropocene” in Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies. Ed. Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin. London: Open Humanities Press, 2015, 243.

[19] Chandler, David and Julian Reid. “‘Being in Being’: Contesting the Ontopolitics of Indigeneity.” The European Legacy 23.3 (2018): 254. DOI: 10.1080/10848770.2017.1420284

[20] Chandler and Reid, “‘Being in Being,'” 257.

[21] Chandler and Reid, “‘Being in Being,'” 259.

[22] Shotwell, Alexis. Against Purity: Living in Ethically Compromised Times. University of Minnesota Press, 2016, 38.

[23] Quoted in Shotwell, 36.

[24] Tsing, Anna. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press, 2015, 33.

For the 2018 American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (ASECS) conference program, Katarzyna Bartoszynska and Eugenia Zuroski chaired a roundtable responding to the V21 Collective’s intervention in nineteenth-century studies and the possibilities it presented for reflecting on current problems and critical approaches in eighteenth-century studies. Additional contributions to the roundtable can be found here.

For the 2018 American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (ASECS) conference program, Katarzyna Bartoszynska and Eugenia Zuroski chaired a roundtable responding to the V21 Collective’s intervention in nineteenth-century studies and the possibilities it presented for reflecting on current problems and critical approaches in eighteenth-century studies. Additional contributions to the roundtable can be found here.

From a dedicated and, I guess, decent enough scholar to an

From a dedicated and, I guess, decent enough scholar to an

In addition to publishing work on Wycherley, Dryden, Pepys, Cibber, Garrick, and Sheridan, my love of and experiences in the theater demanded that I write into the novel a number of scenes set at the Kings Theatre. Here I was forced to give Tom Killigrew the old heave-ho and replace him with a fictional character involved in the comings and goings of the plots. But actual actors and actresses are mentioned and/or discussed (some substantially) by the characters, as are some forty other historical persons—from Peter Lely and the Duke of York to Queen Catherine and Louise de Kérouaille.

In addition to publishing work on Wycherley, Dryden, Pepys, Cibber, Garrick, and Sheridan, my love of and experiences in the theater demanded that I write into the novel a number of scenes set at the Kings Theatre. Here I was forced to give Tom Killigrew the old heave-ho and replace him with a fictional character involved in the comings and goings of the plots. But actual actors and actresses are mentioned and/or discussed (some substantially) by the characters, as are some forty other historical persons—from Peter Lely and the Duke of York to Queen Catherine and Louise de Kérouaille.

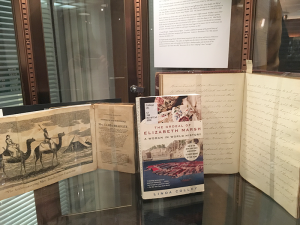

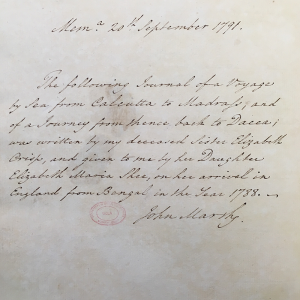

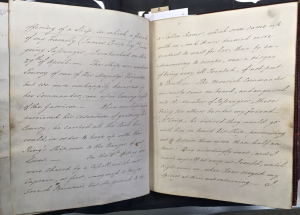

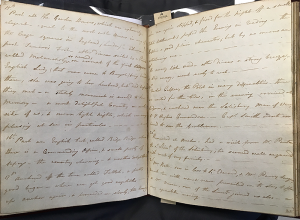

As material documents, the manuscripts indicate the different processes involved in recording and creating the memories of Marsh’s experiences on paper and make them available for posterity. The two—Marsh’s Moroccan captivity memoir and her East Indian tour diary—were bound together by John Marsh, her brother, in red leather. A bookplate bears his name, and notes inserted by him introduce the memoir and the diary, placing them in the context of her life. The memoir appears to be written in John’s neat hand and the diary in Elizabeth’s own, which he explains was given to him by her daughter, Elizabeth.

As material documents, the manuscripts indicate the different processes involved in recording and creating the memories of Marsh’s experiences on paper and make them available for posterity. The two—Marsh’s Moroccan captivity memoir and her East Indian tour diary—were bound together by John Marsh, her brother, in red leather. A bookplate bears his name, and notes inserted by him introduce the memoir and the diary, placing them in the context of her life. The memoir appears to be written in John’s neat hand and the diary in Elizabeth’s own, which he explains was given to him by her daughter, Elizabeth.

The Hollow Tree is set in New England at the beginning of the Revolutionary War. The rupture in familial and social relationships caused by competing loyalties to the Crown and the nascent United States are depicted through the experiences of Phoebe Olcott, the daughter of a Patriot, who, after his death, goes to live with her Loyalist relatives, the Robinsons, in a small town in Vermont, where the Loyalists are in the minority. Deborah Williams, whose husband, John, is rumored to be fighting on the British side, and her four children are dragged from their house in the early hours of the morning, forced into their oxcart, and sent away with a few possessions; a prized family clock is stolen from the cart. When Deborah protests, “Where will we go? We’ll starve!” the ringleader replies, “Starve if you must…that ain’t no never mind of ourn” (22). Meanwhile, Phoebe learns that her beloved cousin, Gideon, is a spy for the British. The next morning, his body is found hanging from the “Liberty Tree”: “On his shirt a note was pinned. It read ‘Death to all Traitors and Spies’” (32). Her cousin Anne attacks her: “You did this. You and your father and his rebel friends!” (33). Bereft, she visits the place where she, Gideon, and Anne used to meet. Reaching into a hollow tree where they had left messages to each other, she finds a packet “addressed to Brigadier-General Watson Powell, at Fort Ticonderoga.” The packet is wrapped in a paper directing that, should Gideon be captured, it should be delivered to the Mohawk leader, Elias Brant (35-36). The text is in code, but it contains an uncoded request for safe passage for three New York families, the Collivers, the Andersons, and the Morrisays.

The Hollow Tree is set in New England at the beginning of the Revolutionary War. The rupture in familial and social relationships caused by competing loyalties to the Crown and the nascent United States are depicted through the experiences of Phoebe Olcott, the daughter of a Patriot, who, after his death, goes to live with her Loyalist relatives, the Robinsons, in a small town in Vermont, where the Loyalists are in the minority. Deborah Williams, whose husband, John, is rumored to be fighting on the British side, and her four children are dragged from their house in the early hours of the morning, forced into their oxcart, and sent away with a few possessions; a prized family clock is stolen from the cart. When Deborah protests, “Where will we go? We’ll starve!” the ringleader replies, “Starve if you must…that ain’t no never mind of ourn” (22). Meanwhile, Phoebe learns that her beloved cousin, Gideon, is a spy for the British. The next morning, his body is found hanging from the “Liberty Tree”: “On his shirt a note was pinned. It read ‘Death to all Traitors and Spies’” (32). Her cousin Anne attacks her: “You did this. You and your father and his rebel friends!” (33). Bereft, she visits the place where she, Gideon, and Anne used to meet. Reaching into a hollow tree where they had left messages to each other, she finds a packet “addressed to Brigadier-General Watson Powell, at Fort Ticonderoga.” The packet is wrapped in a paper directing that, should Gideon be captured, it should be delivered to the Mohawk leader, Elias Brant (35-36). The text is in code, but it contains an uncoded request for safe passage for three New York families, the Collivers, the Andersons, and the Morrisays. Shadow in Hawthorn Bay pulls together three of the dominant cultures in the settlement of Upper Canada: the First Nations, the Loyalists, and the Scottish immigrants. It takes place in 1815-1816, three years after the War of 1812. In her brief biography, Laura Secord: A Story of Courage, Lunn explains, “Neither the British nor the Americans won the war. The only people who really won were the Canadians. The boundary lines between British North America and the United States remained unchanged” (n.p.). One of the characters in Shadow in Hawthorn Bay, who arrived there as a child, describes it more personally: “Then, when we hadn’t more than just gotten ourselves settled into these backwoods—not quite thirty years later—didn’t those old Yankee neighbours come along and start another war! They thought they’d kick us out of here too. Well, I guess they got a surprise!” (105-106).

Shadow in Hawthorn Bay pulls together three of the dominant cultures in the settlement of Upper Canada: the First Nations, the Loyalists, and the Scottish immigrants. It takes place in 1815-1816, three years after the War of 1812. In her brief biography, Laura Secord: A Story of Courage, Lunn explains, “Neither the British nor the Americans won the war. The only people who really won were the Canadians. The boundary lines between British North America and the United States remained unchanged” (n.p.). One of the characters in Shadow in Hawthorn Bay, who arrived there as a child, describes it more personally: “Then, when we hadn’t more than just gotten ourselves settled into these backwoods—not quite thirty years later—didn’t those old Yankee neighbours come along and start another war! They thought they’d kick us out of here too. Well, I guess they got a surprise!” (105-106).