Restoration Printed Fiction

Bibliographers have done much important work on the history of the novel in the long eighteenth century. Scholars are indebted to bibliographies from McBurney’s Check List of English Prose Fiction, 1700-1739 to Beasley’s Novels of the 1740s to Raven’s British Fiction, 1750-1770 and Garside et al.’s The English Novel, 1770-1829; these works form the foundation of a great deal of scholarship. But there are some things that bibliographies cannot do. When I set out to plan a book chapter on fiction in the years 1660-1700, I found very little that could serve as a guide to help me identify which texts would be most useful and important to read. The Early Novels Database was promising, but was not then available, and in any case was focused on texts held in one particular library. So I began compiling what was at first a simple list of titles drawn from older bibliographies and gradually became a spreadsheet and then a database. As I worked on the initial list, it became clear that in order to decide what to read, I needed to know more about each text’s material and paratextual features: which texts, for instance, were fully epistolary, and which included letters in the fiction? Which texts had addresses to the reader, and which had dedications? And of course, as I began consulting EEBO scans to identify these features, other features also struck me as worthy of note: indexes, chapters, tables of contents, and so on. And as I gathered this information, it occurred to me that other scholars might be interested in a resource like this.

Thus was born the Restoration Printed Fiction database, now available online. It catalogs metadata for the 394 works of fiction published between 1660 and 1700. To generate this list of fiction, entries were drawn from three main bibliographic sources (with some additions): Paul Salzman’s English Prose Fiction 1558-1700, Robert Letellier’s The English Novel, 1660-1700, and Robert Adams Day’s Told in Letters. For the purposes of the database, fiction was defined very broadly; given the novel genre’s emergent status at the time, it makes little sense to apply any kind of strict definition that would not have operated for contemporary readers. If one of the bibliographies (or another scholarly source) treated it as fiction, it was included in the database. This broad approach makes it possible for scholars to cast a wide net when considering the nature of fiction. Also, I’ve only included the first printing in this period of a given text: If a text was first published before 1660, I included the first edition that was published after 1660; for texts first published after 1660, only the first edition is listed. In a later phase of the project, it may be possible to include subsequent editions, which would be helpful in gauging the popularity of texts.

Each entry includes basic bibliographical information about the text, such as author (when known), title, bookseller and printer (when known), and date. This kind of metadata allows users to search for particular booksellers or even particular printers, thus making it possible to begin to answer questions such as whether any booksellers may have begun to specialize in fiction in this period, or whether it was more common for a bookseller to publish only one or two works of fiction. How significant is it, for example, that Samuel Briscoe appears as bookseller on fourteen title pages? Do the fifty-four texts not listing a bookseller have anything in common? Other kinds of metadata, of course, make possible other kinds of research questions. The RPF database also includes metadata about several kinds of paratexts, such as dedications, prefaces, addresses to the reader, and prefatory poems. This metadata becomes especially interesting when we search for texts that have more than one of these paratexts. Are dedications more common in conjunction with prefatory poems, for instance, than with other paratexts? Interestingly, of these 394 fictions, sixteen have three paratexts, but none have all four types — and 120 have no paratexts at all. Other researchers might be interested in fictions that are divided into chapters, or fictions that appear with a licensing statement, or fictions that give errata; all of these things are discoverable in the RPF.

A crucial part of the process of producing the RPF was finding a way to make it available to others. Dr. Michael Faris, my colleague at Texas Tech, and then Director of the English Department’s Media Lab, made this possible. Dr. Faris did the coding that makes the searchable database available to others, a process which entailed meeting to understand the content and aims of the database, teaching me how to generate something he could then use as a basis to work with, and writing the code that allows the resource to be useful to scholars. Such collaborative work is especially important in digital humanities work because bringing different skill sets together enables new kinds of work and new kinds of resources that, we hope, will continue to generate new scholarly questions and work.

Writing this book was a great pleasure because it allowed me to investigate one of my favorite forms of fiction while employing my scholarly interest in the development of the novel. I realized that I have been reading historical fiction for most of my life; the first playground reading recommendation that I remember was from a classmate who loved Elizabeth Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond. In the young adult fiction section I return to another early love, Rosemary Sutcliff, whose books I first discovered on those magical shelves of books at the back of my elementary and middle school classrooms. The Dawn Wind is the one I remember most clearly from those days; this book allowed me to discover more of her work. The good news is that, even after years of scholarly investigation, I still read historical fiction for pleasure.

Writing this book was a great pleasure because it allowed me to investigate one of my favorite forms of fiction while employing my scholarly interest in the development of the novel. I realized that I have been reading historical fiction for most of my life; the first playground reading recommendation that I remember was from a classmate who loved Elizabeth Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond. In the young adult fiction section I return to another early love, Rosemary Sutcliff, whose books I first discovered on those magical shelves of books at the back of my elementary and middle school classrooms. The Dawn Wind is the one I remember most clearly from those days; this book allowed me to discover more of her work. The good news is that, even after years of scholarly investigation, I still read historical fiction for pleasure. The Great Forgetting: Women Writers Before Austen

The Great Forgetting: Women Writers Before Austen As any reader of The 18th-Century Common knows, the last quarter century has witnessed the astonishing digitization of thousands of texts from the past: novels, poems, essays, histories, plays, many of them available for free. For scholars, the creation of this Digital Republic of Learning has (on the whole) been a boon, enabling new modes of inquiry that could barely have been imagined a generation ago. For students, however, the digitization of the archive has been a more mixed blessing. As newcomers to the field, students can very easily find themselves overwhelmed by the sheer abundance of material that shows up in the simple Google search that is likely to be their first means of access. Students are unlikely to know how to judge of the quality or authenticity of what they find, or to be able to recognize the difference between a well-edited text and something with virtually no authority whatsoever. Texts are haphazardly distributed, some behind commercial paywalls such as

As any reader of The 18th-Century Common knows, the last quarter century has witnessed the astonishing digitization of thousands of texts from the past: novels, poems, essays, histories, plays, many of them available for free. For scholars, the creation of this Digital Republic of Learning has (on the whole) been a boon, enabling new modes of inquiry that could barely have been imagined a generation ago. For students, however, the digitization of the archive has been a more mixed blessing. As newcomers to the field, students can very easily find themselves overwhelmed by the sheer abundance of material that shows up in the simple Google search that is likely to be their first means of access. Students are unlikely to know how to judge of the quality or authenticity of what they find, or to be able to recognize the difference between a well-edited text and something with virtually no authority whatsoever. Texts are haphazardly distributed, some behind commercial paywalls such as  Our projects intend to improve the quality of eighteenth-century texts available for students, general readers, and scholars, and to enlist students in the project of producing them.

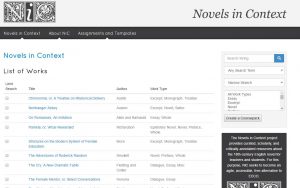

Our projects intend to improve the quality of eighteenth-century texts available for students, general readers, and scholars, and to enlist students in the project of producing them.  Novels in Context

Novels in Context ‘

‘