We might say that of the many topics we 18th-centuriests study, the “Age of Revolutions” tops the list. The French and American Revolutions have long been examined as crucial turning points in the history of the modern world, and we tend to think of the “before” and “after” as two distinct periods. However, for almost as long, we in the West studied the “Age of Revolutions” without paying much attention to what is arguably the most important of the era’s political transformations: the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804).

In recent decades, important work has been done to deconstruct processes of “silencing” the Haitian Revolution and to reconstruct the Haitian archive. The most successful revolt by enslaved persons in history, the Haitian Revolution resulted in a completely autonomous antislavery, postcolonial nation in 1804, and shocked the wider world. Haiti has struggled to deal with this shock for most of its existence. It took decades for Great Britain and France to recognize Haitian independence. The United States waited over half a century.

Unsilencing Haiti’s Revolution and inserting it into the intellectual framework of the “Age of Revolutions” requires conceptual as well as material reexaminations. An important step is the recovery and reading of Haitians’ own words about their country’s history. For example, until now, few students of the Revolution have read the first novel written by a Haitian author, Stella (1859), which is also a text about the Haitian Revolution.

Émeric Bergeaud wrote Stella hoping that the form of the novel would draw more interest to his country’s history. Describing a tension between history and literature, he writes:

History can tell only what it knows. Its sight, limited to the horizon of natural things, has trouble knowing the truth that shines behind that horizon. The miraculous is not within its domain. History leaves the field of mystery to the Novel. (86)

In his explanation, Bergeaud was being clever even as he was being poetic. Tired of reading the slanderous accounts of the Haitian Revolution published in France, Great Britain, and the United States, the novelist wanted to be sure that his readers would instead know Haiti’s great foundational myth and recognize the story as the miracle that it was.

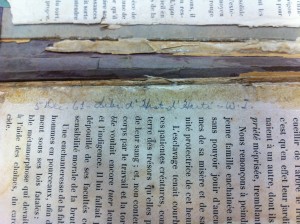

A note providing clues as to the provenance of one of the rare copies of the second edition of Bergeaud’s novel, published at the behest of his widow in 1887. This copy was acquired by the University of Florida in 1961 from the Librairie d’Histoire d’Haïti, which was a famous library and bookstore in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Thanks to this note, we know that the work did circulate in Bergeaud’s homeland even though both of its nineteenth-century editions were printed in Paris.

Out of print for over a century, Stella has often been overlooked. This neglect is partly due to a nineteenth-century colonial mentality that denigrated Haiti and Haitians, constantly judging them against standards established for the purpose of exclusion. It is also due to Bergeaud’s own obscurity—he died in exile in 1858—and the fact that few, if any, physical copies of the original editions survive. These circumstances have meant that literature by early postcolonialists like Bergeaud has never received the attention that it deserves.

A new English translation of Émeric Bergeaud’s 1859 novel aims to aid in the unsilencing processes and to invite Anglophone readers to examine this period more fully. Bergeaud’s insistence that Haiti is the true inheritor of republicanism helps us to understand how Haitians viewed their history in terms of the “Age of Revolutions” well before Western academics began making similar connections.

Recovered texts and new translations like this one offer a means to chip away at the power of the colonial mentality and to challenge the silencing of what we might call the most significant of the age’s revolutions.