When we put out the call for participants on this roundtable, we asked whether eighteenth-century studies needed its own V21 moment, but we must confess that in thinking about the relationship between the two communities, we found ourselves wondering, instead, whether V21 needs eighteenth-century studies. Many eighteenth-centuryists—as Katarzyna Bartoszynska noted while attending the inaugural V21 Symposium—will have read many of the texts and theorists whose names circulate in Victorian Studies, but can the same be said of work in our field, for scholars outside of it? Could the more idiosyncratic status of eighteenth-century literature within literary studies account for the fact that some of what V21 identifies as pressing problems for Victorianists do not similarly trouble scholarship in our field? Presentism, for instance: not only do we not shy away from presentism, we are in fact continuously called upon to articulate the bearing our texts, and our work, have on the present, if only to persuade students to read it.

When we put out the call for participants on this roundtable, we asked whether eighteenth-century studies needed its own V21 moment, but we must confess that in thinking about the relationship between the two communities, we found ourselves wondering, instead, whether V21 needs eighteenth-century studies. Many eighteenth-centuryists—as Katarzyna Bartoszynska noted while attending the inaugural V21 Symposium—will have read many of the texts and theorists whose names circulate in Victorian Studies, but can the same be said of work in our field, for scholars outside of it? Could the more idiosyncratic status of eighteenth-century literature within literary studies account for the fact that some of what V21 identifies as pressing problems for Victorianists do not similarly trouble scholarship in our field? Presentism, for instance: not only do we not shy away from presentism, we are in fact continuously called upon to articulate the bearing our texts, and our work, have on the present, if only to persuade students to read it.

For some time, many of us in eighteenth-century studies—as reflected in the institution of the “long eighteenth century”—have proceeded with an arguably irreverent approach to historical periodization, encroaching on both the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries in order to posit wide-ranging (or what some anonymous reviewers have described as “recklessly broad”) theoretical arguments. We routinely reach to material beyond the historical eighteenth century to think about what we nevertheless consider “eighteenth-century problems.” This tendency was observable in the roundtable: we were struck by how little mention there was of eighteenth-century texts. Rather than rely primarily on eighteenth-century thinkers to frame their approach to the V21 manifesto, panelists turned, for instance, to E. M. Forster and Matthew Arnold (though, to be fair, Sandra Macpherson emphasized how much Arnold is relying on Burke). On the one hand, this reaffirmed our sense that dix-huitiemistes are voracious readers who eagerly join in the kinds of “multi-field and multi-disciplinary conversations” that the V21 manifesto calls for. As Stephanie Insley Hershinow points out, a kind of “naïve synchronism” has served many of us well, particularly in the classroom, and may be leveraged to foster not only good scholarship but also new forms of public writing; such an approach could elevate and “bring in” the kinds of nimble thinking the academic precariat is already being asked to do, but without institutional recognition. But if we want Victorianists and other specialists outside our field to reciprocate with an occasional deep dive into our texts—the literature and philosophy of the eighteenth century, as well as scholarship on it—who would we point them to?

Secondly—and these responses may reveal to V21-ists how people outside the field see them!—we had not expected presentism to be such a central point in the conversation. Indeed, of all the issues raised in the V21 manifesto, this seemed like the one least troubling to eighteenth-centuryists (though, with the contorted logic of the psyche, this may well be precisely why everyone was drawn to it). Carrying the conversation forward, it seems clear to us that beyond the question of presentist methods (strategic or not), we must also continue to think about the critical reassessment of antiquarianism and uncritical historicism, both within the eighteenth century and in our studies of it; the fear of our work not being compelling to scholars outside the discipline; the call for more rigorous theorizing, and for not opposing history and theory); the rethinking of form and formalism, including what Jonathan Kramnick describes as “form detached from politics,” and its relationship to an understanding of literary form, in Sandra Macpherson’s words, as “politics by another means.” While, as several panelists argued, eighteenth-century studies is already doing a lot of the things V21 calls for, and has done them well, we must commit not only to continuing in these paths but also to doing other and better work as well. How might we more effectively converse across fields and disciplines? How do we generate multiple modalities and new institutional frameworks? And, crucially for many of us engaged in this conversation, what is the relationship between these approaches and the mandate to assess academia and its projects in light of both colonization and decolonization?

The wonderful responses of the panelists strongly suggest that eighteenth-century texts and scholars offer a rich resource for the robust theorization of presentism—a commitment to recognizing how the pressures of the present generate both the past and the future as epistemological objects—and an excellent model of synthetic thinking and dialogue between fields. As Jonathan Kramnick points out, when it comes to present-day matters, none of us has any particular expertise. Rather, “we bring our expertise and our methods of explanation to political or ethical matters as they take shape in materials with which we are intimately familiar and about which we have something to say particular to our expertise and training.” Travis Chi Wing Lau urges us to consider how even historicist knowledges are presentist formations, since expertise is forged within the conditions of the present. Rather than disavow the “present in the past,” he argues, we must attend to how we “listen” to the past from our own particular, present positions: “what are we training ourselves to hear, to tune out, or even fail to hear all together?” Laura E. Martin draws attention to the unique quality of the eighteenth-century materials on which our expertise is focused, namely, that we recognize them as works-in-progress, simultaneously different and similar to present phenomena, having not yet coalesced into their more familiar forms. Where the V21 Manifesto asserts that “we are Victorian,” Laura E. Martin shows us that it is because of the ways in which we are not of the eighteenth century that the “transitional character [of C18 objects] gives us a useful model for understanding the dialectical relationship between our present and our past.”

Finally, as to the question of institutional frameworks and new modalities: what are the best ways to produce future collaborations, not only across V21 and eighteenth-century studies, but broadly across various fields and emergent collectives? Borders between eighteenth-century scholars, Romanticists, and Victorianists grow ever blurrier, and we are not the only V21 affiliates whose work fits in more with ASECS than NAVSA. Is the time ripe for a friendly takeover, a broadening of the tent? Are V21’s intellectual goals bigger than Victorianism—are they, in fact, a clarion call for literary studies as a whole? Or do those of us working in the eighteenth century need, instead, to start our own collective, and encourage cross-overs? Discussion in the panel’s Q&A suggested that such an organization would have as one of its objectives a commitment to antiracist and anticolonial work in our field, joining the work of groups such as Bigger6 in Romantic studies, ShakeRace in early modern studies, and the Medievalists of Color. (Since the recent ASECS meeting, we have added the BIPOC18 collective to this list). While V21 is clearly engaged in such work—as Anna Kornbluh pointed out, V21 is motivated by the postcolonial call to break down the national and historical frameworks through which literary studies have reproduced imperialism—this goal is not explicitly part of the manifesto. Should it be? Or, rather than perpetually revise our mission statements, should we focus on making collectives and building coalitions, respecting each organization’s way of approaching the big picture?

One thing that the V21 Collective has done beautifully is actively to integrate graduate student, non-tenure-track, and early career researchers in ways that allow them to feel (correctly!) that it is their platform as much as anyone else’s. It has served as a model for other collectives in this regard. We believe that, in our shared but inequitable present, providing a “home” for institutionally disenfranchised peers, and practicing non-hierarchical methods of interaction, is one of the primary reasons we need new platforms, genres, and scholar-activist communities in our fields right now. Whether or not we organize a “V21 for the C18,” how might we best provide space for active collaboration across not only periods but also differentials of institutional power? One thing we have observed as C18-based affiliates of V21 is that traditional periodizations are, in fact, not a separate issue from the question of how institutions organize power. Building new coalitions in defiance of hierarchy necessitates transhistorical and cross-field thinking. We certainly long for academic frameworks and infrastructures that would put us in touch not only with Victorianists, or Modernists, but also Early Modernists and Medievalists, of all ranks. It seems vital that we routinely remind each other that one period’s “emergent objects” can be another’s foregone conclusion, and to take stock of the way our different knowledges appear from each others’ perspectives. Let’s not lose sight of the fact that one of the reasons we, as eighteenth-centuryists, ended up in V21’s orbit is because its work is so exciting! In a present that is so bleak in so many ways, we all need the gravitational pull of concerted collective effort to stay in motion. We feel the possibilities of broader collaboration, and of circulating knowledges along new paths, as an influx of energy. How might we reciprocate and carry this energy forward by making eighteenth-century studies a vitalizing resource beyond the period, the discipline, the academy?

For the 2018 American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (ASECS) conference program, Katarzyna Bartoszynska and Eugenia Zuroski chaired a roundtable responding to the V21 Collective’s intervention in nineteenth-century studies and the possibilities it presented for reflecting on current problems and critical approaches in eighteenth-century studies. Additional contributions to the roundtable can be found here.

From a dedicated and, I guess, decent enough scholar to an

From a dedicated and, I guess, decent enough scholar to an

In addition to publishing work on Wycherley, Dryden, Pepys, Cibber, Garrick, and Sheridan, my love of and experiences in the theater demanded that I write into the novel a number of scenes set at the Kings Theatre. Here I was forced to give Tom Killigrew the old heave-ho and replace him with a fictional character involved in the comings and goings of the plots. But actual actors and actresses are mentioned and/or discussed (some substantially) by the characters, as are some forty other historical persons—from Peter Lely and the Duke of York to Queen Catherine and Louise de Kérouaille.

In addition to publishing work on Wycherley, Dryden, Pepys, Cibber, Garrick, and Sheridan, my love of and experiences in the theater demanded that I write into the novel a number of scenes set at the Kings Theatre. Here I was forced to give Tom Killigrew the old heave-ho and replace him with a fictional character involved in the comings and goings of the plots. But actual actors and actresses are mentioned and/or discussed (some substantially) by the characters, as are some forty other historical persons—from Peter Lely and the Duke of York to Queen Catherine and Louise de Kérouaille.

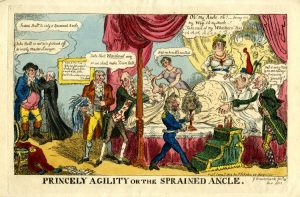

Anne and William’s wedding was held in March at St. James’s Chapel, which had been richly decorated for the occasion by the celebrated architect and painter William Kent. A contemporary engraving of the ceremony captures the prince and princess with hands clasped in the act of exchanging vows before the Archbishop of Canterbury, while ostentatiously dressed courtiers fill the chapel, gossiping and fanning themselves flirtatiously. [9] The wedding was thoroughly documented in almost every London newspaper, and writers emphasized the size of the crowds at the palace, the rich appearance of the nobility, and the voluntary festivities of London’s citizenry, which included the illumination of the Monument and Ludgate with glass lamps, plentiful bonfires, and fireworks. The Daily Journal published a laboriously detailed narrative of the entire wedding procession to and from the chapel, concluding with a public dinner in the State Ballroom, before the nobility filed through the prince and princess’s bedchamber to view them sitting up in their marriage bed “in rich undress.” The London Evening Post and the Penny London Post offered rambling descriptions of the wedding costumes and other finery observed at court. The bride wore diaphanous “Virgin Robes of Silver Tissue, having a train six Yards long, laced around with a massy Lace, adorn’ed with Fringe and Tassels; on the Sleeves were several Bars of Diamonds of great value; the Habit was likewise enrich’d with several Rows of oriental Pearl.” The women of the beau monde donned “fine laced Heads, dress’d English,” and their dresses featured “treble Ruffles, one tack’d up to their Shifts in quil’d Pleats and two hanging down; the newest fashion’d Silkes were white Paduasoys, with large Flowers of Tulips, Peonies, Emmonies, Carnations, &c. in their proper Colours, some wove in Silk, and some embroidered.” Other papers claimed that the “Embroidery and Beauty” of the princess’s wedding clothes “exceed any thing that has been ever seen here, tho’ all of Manufactures of this Kingdom.” [10] These lengthy and exacting descriptions of fashionable and fine court costume as reproduced in metropolitan newspapers broadcast important political messages. Expensive and newly purchased court attire was used to demonstrate allegiance to the crown and respect for the person of the monarch, while careful accounts of hairstyles, dress cuts, and fabric patterns portrayed the court and royal family as taste leaders who followed fashion trends and encouraged native industry. [11] At the same time, the wedding inspired the production of a whole range of commemorative commercial objects for consumers in Britain and the Netherlands, including medals, highly ornamental engraved paper fans, and enameled porcelain bowls decorated with the portraits of Anne and William, who seem to gaze into each other’s eyes. [12]

Anne and William’s wedding was held in March at St. James’s Chapel, which had been richly decorated for the occasion by the celebrated architect and painter William Kent. A contemporary engraving of the ceremony captures the prince and princess with hands clasped in the act of exchanging vows before the Archbishop of Canterbury, while ostentatiously dressed courtiers fill the chapel, gossiping and fanning themselves flirtatiously. [9] The wedding was thoroughly documented in almost every London newspaper, and writers emphasized the size of the crowds at the palace, the rich appearance of the nobility, and the voluntary festivities of London’s citizenry, which included the illumination of the Monument and Ludgate with glass lamps, plentiful bonfires, and fireworks. The Daily Journal published a laboriously detailed narrative of the entire wedding procession to and from the chapel, concluding with a public dinner in the State Ballroom, before the nobility filed through the prince and princess’s bedchamber to view them sitting up in their marriage bed “in rich undress.” The London Evening Post and the Penny London Post offered rambling descriptions of the wedding costumes and other finery observed at court. The bride wore diaphanous “Virgin Robes of Silver Tissue, having a train six Yards long, laced around with a massy Lace, adorn’ed with Fringe and Tassels; on the Sleeves were several Bars of Diamonds of great value; the Habit was likewise enrich’d with several Rows of oriental Pearl.” The women of the beau monde donned “fine laced Heads, dress’d English,” and their dresses featured “treble Ruffles, one tack’d up to their Shifts in quil’d Pleats and two hanging down; the newest fashion’d Silkes were white Paduasoys, with large Flowers of Tulips, Peonies, Emmonies, Carnations, &c. in their proper Colours, some wove in Silk, and some embroidered.” Other papers claimed that the “Embroidery and Beauty” of the princess’s wedding clothes “exceed any thing that has been ever seen here, tho’ all of Manufactures of this Kingdom.” [10] These lengthy and exacting descriptions of fashionable and fine court costume as reproduced in metropolitan newspapers broadcast important political messages. Expensive and newly purchased court attire was used to demonstrate allegiance to the crown and respect for the person of the monarch, while careful accounts of hairstyles, dress cuts, and fabric patterns portrayed the court and royal family as taste leaders who followed fashion trends and encouraged native industry. [11] At the same time, the wedding inspired the production of a whole range of commemorative commercial objects for consumers in Britain and the Netherlands, including medals, highly ornamental engraved paper fans, and enameled porcelain bowls decorated with the portraits of Anne and William, who seem to gaze into each other’s eyes. [12]

Sheffield: Print, Protest and Poetry, 1790-1810

Sheffield: Print, Protest and Poetry, 1790-1810