Before the species-ending plague, the characters in Mary Shelley’s novel The Last Man (1826) dream of a world without disease. Early in the first volume, Adrian—only son of England’s final reigning monarch—argues that, here at the end of the twenty-first century, “the choice is with us; let us will it, and our habitation becomes a paradise. For the will of man is omnipotent, blunting the arrows of death, soothing the bed of disease and wiping away the tears of agony” (76) [1]. Others agree: not only has smallpox been eradicated, but the narrator also records, many believe, that in the near future of their English republic, “the state of poverty was to be abolished” and all “disease was to be banished” (106) [2].

The final volume of Shelley’s novel proves these characters wrong, as death comes for all members of the human species save one. Although the novel belabors the effects of the plague (when I taught the novel a few semesters ago, one of my students described it as a never-ending set of death scenes), the plague’s origin and means of transmission remain mysterious. “It was called an epidemic,” Verney writes, “but the grand question was still unsettled of how this epidemic was generated and increased” (231). An “invincible monster” (221), the plague appears alternately in the figure of a woman—“Queen of the world” (346)—and as the word “plague” itself [3]. Verney contends that the plague is miasmatic rather than contagious, caught when one breathes air “empoisoned” (233) by rotting animal and vegetable matter in heat, rather than by physical contact with contagious bodies—infected breath or sweat, or even goods previously handled by a person with the plague. Importantly, as a miasmatic disease, Verney argues that there is no need for England to establish quarantine, or to turn away the sick. However, literary critics have been skeptical about Verney’s own explanations, not least because his admonitions to care for the sick are belied by his own racist acts of self-protection, as when, rushing back to his family in Windsor, he rejects the “convulsive clasp” of a “negro half clad, writhing under the agony of disease” (336). It is from this encounter that Verney himself appears to catch the disease and then becomes immune to its power [4].

Reading Contagion: The Hazards of Reading in the Age of Print

While my own recent publication, Reading Contagion (2018), postulates that The Last Man’s plague might appear so very inexplicable because it revives now obsolete beliefs about the hazards of reading—the various contagions eighteenth-century authors speculate might be spread by the form and contents of printed texts—I’m more interested here in the novel’s rebuke of fantasies about a world without disease. In our own moment, this rebuke resonates. Today, epidemiologists and public health experts warn about the potential for the vast expansion or virulent return of contagious diseases as one of the catastrophic results of anthropogenic climate change. In a rapidly warming world, researchers caution that localized diseases such as Zika could spread much more widely if disease-carriers like mosquitos find newly warm habitats, or that older pathogens frozen in ice might be released as a result of continued drilling, mining, or melting of permafrost in formerly frozen regions like Siberia [5]. This contemporary concern prompts the question: could Mary Shelley’s novel—which imagines the end of humanity one hundred years in our own future and depicts natural disasters, like floods and earthquakes, alongside an unstoppable plague—be an early warning about the Anthropocene? [6]

I think the answer is rather obviously yes, but indirectly and problematically so. For Shelley’s novel, written in 1826, seems to have its own contemporaneous target, one that we can see in her pointed refusal of the idea that in the future “the state of poverty was to be abolished” and “disease was to be banished.” In England during the 1820s, these are the dreams of a newly formed public health movement—led in part by Thomas Southwood Smith (1788–1861), physician at the London Fever Hospital, and the future ally of sanitation reformer Edwin Chadwick (1800–1890)—both of whom altered longstanding theories of disease. In a series of articles published in the Westminster Review in 1825, Smith argued stridently that—save smallpox—all diseases are miasmatic, the product of climatic conditions in particular places. For Smith, miasmatic (or what he terms “epidemic”) diseases “prevail most in certain countries, in certain districts, in certain towns, and in certain parts of the same town” [7].

“No. 7, PHEASANT COURT, GRAY’S INN LANE – Second-Floor, Front Room” (1850) by National Philanthropic Association (Depicting the Physical Conditions said to Generate Disease)

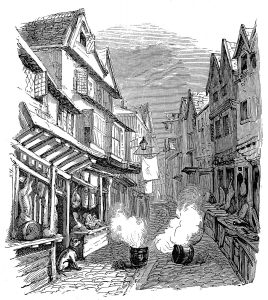

Smith contends that these locations are dispersed across the earth but share the same features: spaces that “are the most low and damp, the worst built and the least sheltered” (144). These locations are dirty, crowded, moist, and unventilated, and as Smith writes, “inhabited by persons who can least afford to pay” (144). When heated, these spaces will putrefy, generating epidemic disease. For Smith this is wholly distinct from contagion, which is a “specific animal poison” (134–35). Contagion is a “palpable” (135) or “morbid matter” (140) secreted by the human body and spread solely by person-to-person contact; epidemic disease is caused by “a certain condition of the air” (135), when the air becomes “charged with noxious exhalations arising from the putrefaction of animal and vegetable matter” (142). This “corrupted atmosphere” (151) is for Smith not itself contagious, but instead local and seasonal.

“Fumigating streets with tar in Exeter” (1849) by Thomas Shapter (Depicting an Attempt to Purge Miasmatic Air)

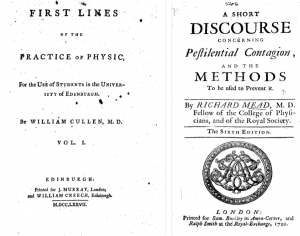

In these articles, Smith revises, by simplification, those complicated causal networks that had been inherent to theories of disease during the eighteenth century. In that earlier period, British physicians postulated that some diseases begin when the air is polluted by the presence of rotting animal or vegetable matter (most likely to occur in hot, moist climates), while others (such as smallpox) originate instead as a specific contagion—infectious matter spread by direct contact with infected bodily fluids, breath, air, or even porous objects (termed “fomites”). But even this distinction between types of diseases remained somewhat fuzzy, as physicians also argued that diseases can transform from miasma to contagion. In the case of the plague, or certain kinds of fevers, physicians argued that even if the disease begins as miasma, it can transform: when enough infected bodies breathe together, that diseased breath saturates and transforms the air, rendering it contagious and capable of spreading over vast distances [8]. Smith’s theories eradicate these complicated causal networks, which locate infectious agency in the interactions among humans and their surrounding worlds—interactions capable of transforming both a disease and its means of transmission.

Title Pages of Richard Mead’s “Discourse Concerning Pestilential Contagion” (1720) and William Cullen’s “Practice of Physic” (1777)

Smith’s writings for the Westminster Review, as well as his later Treatise on Fever (1830), were successful in shifting the beliefs of public health advocates, even if other medical professionals remained unconvinced. Absolute distinctions between contagious and miasmatic diseases and sanitation as a wholesale cure for all diseases were taken up as doctrine by public health reformers, led by Chadwick [9]. As historians and literary scholars including Margaret Pelling, Christopher Hamlin, Mark Harrison, Pamela Gilbert, and Rajani Sudan have emphasized, this shift bolsters an already hardening ideology of native English superiority—of national health—that locates disease solely in improvable locations, usually urban or tropical ones [10]. As these scholars also note, public health’s winnowing of the causes of disease to the physical qualities of particular locations works to minimize concurrent or contributing social and economic factors. Further, cures for diseases could be likewise simplified and rendered politically inoffensive. Because if miasmatic diseases are caused by stagnant air and water, cures could be found in physical acts of cleansing or sanitation—by removing dirt, constructing proper drains to void stagnant water, establishing proper ventilation, or burning away the bad air. The bodies of those persons infected could be similarly cured by being moved to fever hospitals, where they could be treated in pure air.

Dreaming of perfecting human health in Shelley’s moment, then, operates via a simplified causality that erases the agential power of mobile and contingent interactions among collective bodies, air, goods, etc. And, so, one way to read The Last Man is as a critique of that kind of simplification, accomplished when Shelley raises a plague that will not be confined to miasma or cured by sanitation. As such, Verney is proven wrong when he asserts that the plague is generated and spread not by bodies or objects, but only by location, which can be avoided: “as for instance, a typhus fever has been brought by ships to one sea-port town; yet the very people who brought it there, were incapable of communicating it in a town more fortunately situated” (231). And thus to get back to the question of the Anthropocene, Shelley’s novel can be read as critiquing exactly the kind of simplified causal thinking—which sees no agency in interaction itself—that is so debilitating when attempting to comprehend anthropogenic climate change today. For to comprehend climate change we have to understand the importance of both interactions and secondary effects, which can themselves catalyze further catastrophes: for example, that increasing amounts of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere prevent heat from escaping, and that warming causes greater ocean evaporation, and that evaporation causes even greater warming because that vapor absorbs heat and then stays in the atmosphere, and that ever-increasing warming then opens novel pathways for disease vectors, and so on.

“Modern Rome, Campo Vaccino” (1839) by J. M. W. Turner

But what makes The Last Man so very difficult is that, even as it critiques one kind of thinking, it also proffers its own simplification in place of Verney’s mistakes: a plague that only infects humans. I think this is crucial. For what The Last Man can imagine is the particular human hubris of thinking that disease possesses one sole cause—location, which can be improved upon by human action: “let us will it, and our habitation becomes a paradise.” What the novel cannot imagine, though, is our own vast underestimation of our power to do harm to—indeed, to destroy—every element of the non-human world in our interactions with that world. For, as the drastic destruction of insects in the rain forests of Central America or the potential extinction of clouds shows, “the choice is with us; let us will it, and our habitation becomes” . . . [11]

Notes

[1] Mary Shelley, The Last Man. Ed. Morton D. Paley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

[2] During the second volume, Verney asserts, “the plague was not what is commonly called contagious, like the scarlet fever, or extinct small-pox” (231).

[3] The novel’s preoccupation with the word plague—in quotations or italicized, as when Verney reports “the man to whom I spoke, uttered the word ‘plague,’ and fell at my feet in convulsions; he also was infected” (400)—raises the possibility for many scholars that language or story is also responsible for plague’s transmission.

[4] After the dying man’s “breath, death-laden, entered my vitals” (337), Verney experiences fever followed after three days by a miraculous “restoration” (343), which, for Verney, “brought slow conviction that I had recovered from the plague” (343). Verney’s achieved immunity to the disease suggests that, counter to his own arguments, the plague is contagious (like smallpox). Given the novel’s own incoherence about disease, a wide body of productive literary scholarship has explored this question of whether the plague is miasmatic, contagious, or some combination of the two, and why those distinctions might matter. For just some of this incisive work, see Anne Mellor, “Introduction,” The Last Man, edited by Hugh J. Luke, Jr. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), vii-xxiv; Kari E. Lokke, “The Last Man,” The Cambridge Companion to Mary Shelley, edited by Esther Schor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 116-134; Anne McWhir, “Mary Shelley’s Anti-Contagionism: The Last Man as ‘Fatal Narrative,’” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 35. 2 (June 2002): 23-38; Peter Melville, “The Problem of Immunity in Mary Shelley’s The Last Man,” SEL 47. 4 (Autumn 2007): 825-46; and Siobhan Carroll, “Mary Shelley’s Global Atmosphere,” European Romantic Review 25.1 (February 2014): 3-17. Most recently, Melissa Bailes has rethought these questions by arguing that Shelley’s novel draws upon the work of George Cuvier to represent individual deaths as themselves apocalyptic (“The Psychologization of Catastrophe in Mary Shelley’s The Last Man,” ELH 82.2 [2015]: 671-699).

[5] See, for example, Greg Mercer, “The Link Between Zika and Climate Change” The Atlantic, February 24, 2016, as well as Boris A. Ravich and Mariana A. Podolnaya, “Thawing of Permafrost May Disturb Historic Cattle Burial Grounds in East Siberia.” Global Health Action 4.1 (2011): 1-6.

[6] I am deeply grateful for Kent Linthicum for first suggesting that I think about this question, and for providing important insights from his own work about The Last Man’s many natural disasters. For recent scholarship indicting the novel’s politics of sustainability, see Lauren Cameron, “Questioning Agency: Dehumanizing Sustainability in Mary Shelley’s The Last Man,” in Romantic Sustainability: Endurance and the Natural World, 1780-1830, edited by Ben Robertson (Lanham MD: Lexington Books, 2016): 261-73.

[7] [Thomas Southwood Smith], “Contagion and Sanitary Laws.” Westminster Review 3 (January-April 1825): 37-67, 144.

[8] Early eighteenth-century physician and contagion-expert Richard Mead argues that “when in an evil Disposition of This [corrupted air] they [infectious particles] meet with the subtle Parts, its Corruption has generated [people who are infected with disease], by uniting with them they become more active and powerful, and likewise more durable and lasting, so as to form an Infectious Matter capable of conveying the Mischief to a great Distance from the diseased Body, out of which it was produced” (A Short Discourse Concerning Pestilential Contagion, 6th edition [London: Printed for Sam Buckley in Amen-Corner, and Ralph Smith at the Royal-Exchange, 1720], 12-13). Later in the century prominent physician William Cullen writes of jail fevers: “the effluvia constantly arising from the living human body, if long retained in the same place, without being diffused in the atmosphere, acquire a singular virulence; and, in that state, . . . become the cause of a fever which is highly contagious” (First Lines of the Practice of Physic [4th edition, Edinburgh: Printed for C. Elliot, 1784], 1:81).

[9] As Margaret Pelling explains, while originally referring to quarantine measures (from the French cordon sanitaire), “sanitary” began to include “measures directed towards improvement in comfort and cleanliness” during the time of the first cholera epidemic (Cholera, Fever and English Medicine, 1825-1865 [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978], 30-31). According to Pelling, the term “sanitary,” was first used by Charles McLean, in his arguments against quarantine in the Evils of Quarantine Laws (1824), a primary source for Smith’s articles.

[10] See Pelling, Cholera, Fever; Christopher Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick: Britain, 1800-1854 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Mark Harrison, Climates and Constitutions: Health, Race, Environment, and British Imperialism in India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999) and Medicine in the Age of Commerce and Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); Pamela Gilbert, Cholera and the Nation: Doctoring the Social Body in Victorian England (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2008); and Rajani Sudan, The Alchemy of Empire: Abject Materials and the Technologies of Colonialism (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016). More recently, in Difference and Disease: Medicine, Race, and the Eighteenth-Century British Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), Suman Seth illuminates that it is roughly during this same period (the late eighteenth century) that medical writers themselves begin to distinguish absolutely diseases of temperate and tropical climates, what he terms a “race-medicine” that shares affinity with a “race-science” that is also arguing for absolute distinctions between an ever smaller number of races.

[11] See Damian Carrington, “Plummeting Insect Numbers Threaten the Collapse of Nature” The Guardian, February 10, 2019, and Natalie Wolchover, “A World Without Clouds” Quanta Magazine, February 25, 2019.

This summer more than 100 people, from readers to writers to scholars, will gather at the sixth-annual Jane Austen Summer Program to celebrate the bicentenary of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Attendees of “Northanger Abbey and Frankenstein: 200 Years of Horror” will have the opportunity to hear expert speakers and participate in discussion groups on the gothic-inspired novels. They also will partake in an English tea, dance at a Regency-style masquerade ball, attend Austen-inspired theatricals, and visit special exhibits tailored to the conference.

This summer more than 100 people, from readers to writers to scholars, will gather at the sixth-annual Jane Austen Summer Program to celebrate the bicentenary of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Attendees of “Northanger Abbey and Frankenstein: 200 Years of Horror” will have the opportunity to hear expert speakers and participate in discussion groups on the gothic-inspired novels. They also will partake in an English tea, dance at a Regency-style masquerade ball, attend Austen-inspired theatricals, and visit special exhibits tailored to the conference.