Faculty and students at the University of Pittsburgh at Greensburg are working on a long-range digital project (Digital Archives and Pacific Cultures) to code and analyze the voyage narratives of eighteenth-century European expeditions to the Pacific, together with the English poetry and print media that responded to the published accounts of Pacific voyages. We are attempting to study the cross-cultural significance of European voyages in the Pacific and cultural contact experiences in Oceania and Australia, using digital coding and “text-mining” to collect information from very long voyage records in systematic ways through computational methods.

One phase of our work involves preparing digital editions of Pacific voyage publications by Hawkesworth, Cook, and the Forsters in TEI XML (the language of the Text Encoding Initiative) to meet a world standard for accessible and consistently encoded digital texts. (For more on the Text Encoding Initiative, please see http://www.tei-c.org/index.xml). Some of the voyage accounts we have prepared for the site have not been freely available online in any searchable form before. Some are available in proprietary or public databases but have not, to this point, been united in one place. In addition to preparing editions, we have collected the geographic coordinates recorded in these publications using regular expression matching and autotagging, in order to generate Google Earth & Map views of the voyages. Our Google Earth projections of Wallis’s and Cook’s voyages offer a clickable interface, so that selecting a compass rose point along the voyage brings up a paragraph or block of text from a voyage record describing events recorded in connection with this place. Here is an example.

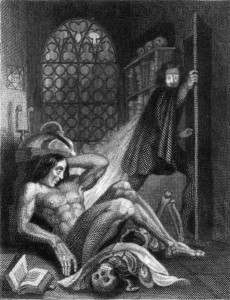

We have also been preparing TEI XML editions of poems, plays, and excerpts from literary and philosophical texts that respond in some way to the Pacific voyage publications.

These texts were located by searching the ECCO and ECCO TCP databases, and we will be adding more material from these resources and the Burney Collection. Our students have been preparing and marking these files to code specific kinds of cultural interactions so that we can study how English texts represented Pacific encounters and identify the types of interactions which seem to have caught the interest of Atlantic-bound media. We’ve also provided an interactive clickable interface to “color-code” the poems, highlighting names of people and places as well as the cultural markup our students have applied: See our edition of Anna Seward’s “Elegy on Captain Cook” (1780). Please see also our edition of Gerald Fitzgerald’s “The Injured Islanders” (1779), produced just before the news of Cook’s death became known in England. We offer Fitzgerald’s poem as a significant contrast to the cultural representations in Seward’s work.

The project began and is developing at the University of Pittsburgh’s Greensburg campus, but the site’s initial development joined a team of faculty and undergraduate students at the Pittsburgh and Greensburg campuses. As the project continues to develop, it combines classroom teaching of digital humanities research methods together with new research to build a publicly accessible resource. Our texts and markup and our data visualization experiments are very much a work in progress and are freely available to the public for reading or to download as the basis of new digital projects under a Creative Commons license. Our site will continue to expand over the next few years as we experiment with topic modelling the Pacific voyage texts and as we develop new maps, search tools, and network graphics, working with new groups of students.