The Great Forgetting: Women Writers Before Austen is a free podcast series addressing the lives and works of eighteenth-century women writers, devised and produced by one journalist and three academics. One day while chatting on Twitter, Helen Lewis (deputy editor of the New Statesman, a leading British weekly magazine focusing on politics and culture) Jennie Batchelor (University of Kent), Sophie Coulombeau (Cardiff University), and Elizabeth Edwards (University of Wales) discovered that they shared not only a love of eighteenth-century women’s writing but also a conviction that the world needed to know more about it. An idea was born: a six-part podcast series, aimed at the non-specialist listener, about the lives, works and legacies of the women who changed the face of literature – but had, from the beginning of the nineteenth century, been gradually subjected to what Clifford Siskin calls “The Great Forgetting.”

The Great Forgetting: Women Writers Before Austen is a free podcast series addressing the lives and works of eighteenth-century women writers, devised and produced by one journalist and three academics. One day while chatting on Twitter, Helen Lewis (deputy editor of the New Statesman, a leading British weekly magazine focusing on politics and culture) Jennie Batchelor (University of Kent), Sophie Coulombeau (Cardiff University), and Elizabeth Edwards (University of Wales) discovered that they shared not only a love of eighteenth-century women’s writing but also a conviction that the world needed to know more about it. An idea was born: a six-part podcast series, aimed at the non-specialist listener, about the lives, works and legacies of the women who changed the face of literature – but had, from the beginning of the nineteenth century, been gradually subjected to what Clifford Siskin calls “The Great Forgetting.”

Each week, we came up with a different theme to shape our conversation. In the first week, Rewriting the Rise of the Novel, we asked: who gets overlooked when we let Defoe, Fielding and Richardson hog the “rise of the novel” narrative? In this episode we aimed to explain the importance of some of the eighteenth century’s most prolific and innovative female novelists; from Aphra Behn and Frances Burney to Eliza Haywood, Maria Edgeworth, and Delarivier Manley. We asked what sorts of challenges these women overcame in order to make it as successful writers, and what flak they received in return. And we spoke about some of our favorite moments in female-authored novels: from Evelina’s odd monkey to the glorious butch of Harriot Freke.

In the second week, we put Bluestocking culture under the microscope. Who were the Bluestockings, why did they matter, and was their footwear really as lurid as we’ve been led to believe? We explained how, through salons hosted by the likes of Elizabeth Montagu, Elizabeth Vesey, and Hester Thrale Piozzi, this group of highly educated women helped shape a new age of sociability and creativity, making it commonplace rather than controversial to assert that a woman might be the intellectual equal of a man. And we also revealed juicy details about Elizabeth Carter’s snuff-snorting habit.

Week three saw us turn to the subject of Sociable Spaces. We focused first on the Lady’s Magazine, asking who wrote it, read it and published it, and how far its subject matter might be defined as “feminine.” We then turned to think about the proliferation of all-female debating societies, such as La Belle Assemblée, in the early 1780s. What topics did women want to chew over? How were their debates alternatively valorised and satirised? And why did these societies die out? Highlights included discussions of eighteenth-century mansplaining in the pages of the Lady’s Magazine, and #everydaysexism in the galleries of the debating chamber.

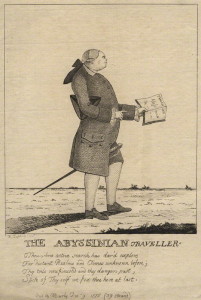

In week four, we examined the Unsex’d Females, advocates of radical politics – and the conservative powerhouses who opposed them. Novelists, poets and pamphleteers including Charlotte Smith, Anna Barbauld, and Mary Wollstonecraft all engaged with major political questions of their day including the French Revolution, the slave trade, and women’s rights – and argued for radical reforms. But not everyone approved of their zeal: Hannah More and Hester Thrale Piozzi argued in favour of conservative agendas, and Richard Polwhele lamented the “Female Band, despising Nature’s Law” in his memorable poetic rant, “The Unsex’d Females.”

Week five saw us roll up our sleeves and enter the ring for Fight Club, each of us slugging it out on behalf of our favorite woman writer of the eighteenth century. Sophie was in Frances Burney’s corner, Liz flew the flag for Hester Thrale Piozzi, and Jennie championed an unusual candidate – “Anomymous.” Who won? Listen to find out…

In the sixth and final week of the podcast, we put the idea of “The Great Forgetting” under the microscope. Why, exactly, do the vast majority of people now draw a blank at the mention of these women’s names? How did they go from enjoying fame and success to obscurity? How did their works shape the literary canon? And why is it important that we remember and celebrate them in an age when female writers and scholars still face disadvantage and marginalization?

The podcast was devised and recorded in early 2016 and broadcast in April and May via the website of the New Statesman. It remains available to stream or download here and through iTunes.

Our hope in creating The Great Forgetting was that we would be able to help a wide non-academic audience to become familiar with these writers and their works, and to stimulate reflection on the gendering of literary prestige in the past and present. In that, we seem to have succeeded: in just the first three weeks, the podcast received almost 3000 listens, exclusive of iTunes downloads. We continue to be delighted and excited to think that, as the podcast remains online, more thousands of people might encounter the writing of women like Aphra Behn, Eliza Haywood, Delarivier Manley, Frances Burney, Hester Thrale Piozzi, Mary Wollstonecraft, Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Hannah More, Ann Yearsley, Phillis Wheatley, Elizabeth Montagu, and Charlotte Smith. We’re beginning to think about ways in which we might integrate the podcasts into our teaching curricula, and we would love to hear from anyone else who has done so.

But, although making the podcast was a rewarding experience, it also provoked some sobering reflections about what happens when traditional academic methodologies meet new media. For example, we were chagrined to discover – even faced with the luxury of over three hours’ airtime – how many women writers we still ended up leaving out. We were abashed to realize that we hadn’t managed to give novelists such as Sarah Scott and Sarah Fielding any attention, while our paucity of female playwrights was another sore point. We spoke far more about the second half of the eighteenth century than the first. In light of this, we were forced to ask ourselves what criteria (aesthetic? biographical? canonical?) we had unthinkingly imposed on our selection process for subjects for the programe, even as we railed against ideas of “literary value” that had been dominant in the past. On a similar note, it was difficult – almost impossible – to credit the academics whose works we drew upon, heavily, in our conversations with Helen. In other words, you can’t add a footnote to a podcast (though we did try to remedy this a bit by providing reading lists every week – see here). With initiatives like this, then, might we run the risk of appearing to present ourselves in glorious intellectual isolation – ironically erasing the work of previous scholars (many of whom are women) even as we argue against that very process?

These, and other issues, preoccupy us as we evaluate the success of the podcast series. If readers of The 18th-Century Common have any feedback, we’d be delighted to hear it.