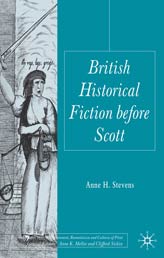

British Historical Fiction Before Scott by Anne H, Stevens

The eighteenth century has served as the backdrop for some of the greatest historical novels, from William Makepeace Thackeray’s The Luck of Barry Lyndon (1844) to Hilary Mantel’s A Place of Greater Safety (1992) and Thomas Pynchon’s Mason and Dixon (1997). But the century also produced a large number of historical novels, many of which are less well known.

Conventional literary history for a long time credited Sir Walter Scott with inventing the genre of the historical novel with his Waverley Novels (1814-32) — a myth that Scott helped to promote. The Waverley Novels were indeed groundbreaking, with record-breaking sales and international influence. The success of Scott’s gripping tales of Scottish history (among other things) inspired other novelists to try their hand at mixing history and fiction, leading to great 19th-century works like Alessandro Manzoni’s I Promessi Sposi (1825), Victor Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), and Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869).

Despite Scott’s influence and popularity, he wasn’t the first historical novelist. It’s always hard to identify “firsts” of any sort, for no writer exists in a vacuum. In the case of the historical novel, you can find precursors and models for the historical novel going all the way back to antiquity. And I mean all the way back — Homer was a historical novelist of sorts, though he wrote in verse. Closer to the modern era, 17th-century French writers such as Mme de Lafayette intermingled fictional and historical characters and events in her great historical novel La Princesse de Clèves (1678).

In the last few decades of the 18th century, historical fiction became very popular with British readers. The novels of the middle of the 18th century tended to be sentimental or comic tales set in contemporary England, modeled after the two leading figures of the day: Samuel Richardson and Henry Fielding. But beginning in the 1760s, the dominance of Richardson and Fielding began to wane, and novels set in different historical eras and geographic locales began to compete for readers’ attention. Dozens of popular novelists produced historical fictions of varying sorts in the half century before Waverley. A few of these writers, such as William Godwin and Maria Edgeworth, are well known to people who study 18th-century literature, but the majority of these novels are by forgotten or even anonymous writers.

The reason for this increase in the production of historical novels, and novels more generally, in the last third of the 18th century, has to do with the growth in popularity of circulating libraries throughout Britain. Circulating libraries were lending libraries, where anyone, for a fee, could borrow volumes of the latest publications. They flourished especially in big cities like London and Edinburgh and in fashionable spa towns like Bath and Cheltenham. Books were very expensive in the 18th century, and public libraries didn’t yet exist, but circulating libraries allowed middle-class readers access to a wide array of publications. Three-volume novels (which could be loaned out simultaneously to three different readers, a volume at a time) were especially popular, and as libraries expanded the demand for new titles grew.

My book British Historical Fiction before Scott (2010) examines the popular historical novels of this era. In it, I look at 85 novels published between 1762 and 1813 to explore how the conventions of the historical novel took shape during this period, how the genre grew out of but eventually branched off from the Gothic tradition, and how it was received by readers and reviewers. These novels show a tremendous amount of variety in setting, style, and quality. The settings can range from the ancient world in Alexander Thomson’s Memoirs of a Pythagorean (1785) to 17th-century France in Ann Yearsley’s The Royal Captives (1795), an early take on the man in the iron mask story. Stylistically these novels range from sentimental weepies like the anonymous Lady Jane Grey (1791) to boys’ adventure tales in James White’s The Adventures of King Richard Coeur-de-Lion (also 1791).

The earliest historical novels I look at are also important texts in the history of the Gothic novel. Thomas Leland’s Longsword, Earl of Salisbury (1762), Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764), and Clara Reeve’s The Old English Baron (1777) often feature prominently in histories of the Gothic novel. All of these texts are set in the Middle Ages and draw upon features of the medieval romance: women in peril, creepy castles, young heroes with mysterious origins, and often supernatural occurrences. At the same time, these Gothic romances also highlight aspects of their historical settings — the Crusades in the case of Walpole, the Barons’ War in the case of Leland, and details of medieval customs in the case of Reeve.

Sophia Lee’s novel The Recess; or, a Tale of Other Times (1783–85) illustrates the intersections and the common origins of Gothic and historical fiction. Critics continually face difficulties in labeling her remarkable novel: it seems to be a Gothic fiction because of its use of conventions such as secret passages and persecuted maidens and its atmosphere of gloom and terror, yet it lacks what has come to be seen as the defining feature of the Gothic, the supernatural. Lee does employ many of the features of the historical novel: the story takes place at a particular historical moment (the late 16th and early 17th centuries), depicts real historical figures (Mary, Queen of Scots, Elizabeth I, the Earl of Essex, James I, and many others), and features major historical events such as Essex’s campaigns in Ireland and Mary’s execution.

After the success of The Recess, the histories of the historical novel and the Gothic novel begin to part ways. In the 1790s especially, the “Gothic” branch of this tree emphasized the supernatural, suspense, and shocks. Matthew Lewis’s The Monk (1796), for example, features a historical setting (the Spain of the Inquisition), yet historical backdrop is subordinate to scenes of horror. In contrast, a different subset of novels aimed to depict scenes from the past, featuring subtitles such as “A Tale, Founded on Historical Facts” (Henry Siddons’s William Wallace, 1791), “A View of the Military, Political, and Social Life of the Romans” (E. Cornelia Knight’s Marcus Flaminius, 1792), and “Anecdotes of Distinguished Personages in the Fifteenth Century” (The Minstrel, 1793) that highlighted the historical source material for the novels and their didactic function. Sites like the Internet Archive, Project Gutenberg, The Hathi Trust, and Google Books have made many of these early historical novels freely available online and to download, so interested readers can now easily explore this corner of literary history.