Thomas Gainsborough. “Mary and Margaret Gainsborough, The Artist’s Daughters,” c. 1756. Victoria and Albert Museum, The Forster Bequest (1876)

“Frenemy” is a word that has been so commonly used in media and everyday conversations that it made its way into the Oxford English Dictionary in 2008. A combination of the words “friend” and “enemy,” the OED defines “frenemy” as “a person with whom one is friendly, despite a fundamental dislike or rivalry; a person who combines the characteristics of a friend and an enemy.” The first appearance of this term happened as early as 1953 when American journalist Walter Winchell used it in his article “How about calling the Russians our Frienemies?” but representations of this double-edged relationship exist from a much earlier date. Even in the eighteenth century, for instance, authors like Eliza Haywood portrayed this sensitive and ambiguous relationship in her works, especially that between women. Today, frenemy is more often used to refer to personal relationships between women so much so that it has become a stereotype, for as Alison Winch contends, “The figure of the toxic friend or ‘frenemy’ is pervasive in girlfriend culture” (57). This stereotype, however, comes from a long history of such representations. While the OED definition, with “a person” as its subject, implies a focus on the emotional attachment between individuals, Haywood’s novels, especially her final novel, show how the word “frenemy” can be applied to a broad and complex range of female relationships.

Although Winch, in her book Girlfriends and Postfeminist Sisterhood, focuses on present-day media representations of women’s friendships, her analysis offers a lens through which eighteenth-century narrative representations of the intersection between the personal and public aspects of female friendship can be examined. As Winch points out, conduct books today that “advise women on how to behave themselves in a neoliberal society where the self is perceived as an entrepreneurial project” (34) also “belong to a specific literary tradition rooted in the eighteenth century, whose objective is to govern gendered behavior as classed” (34). According to Winch, “Women [today] are looking to the lifestyle industries, but also to each other—to girlfriends—for normative performances of femininity” and in the case that “they do not conform to the normalizing impulses of the authors [of conduct books], then the reader is punished through shame” (34). More importantly, Winch introduces the term “gynaeopticon,” the condition in which “the many girlfriends watch the many girlfriends” (5); because “the male gaze is veiled as benign, and instead it is women who are represented as looking at other women’s bodies” (5), the regulating girlfriend gaze is often presented in an intimate manner and is thus “extended to viewers and users [of girlfriend media] in order to engage them in systems of surveillance” (5). Indeed, by shedding light on the significance of the dynamics between women today, Winch’s analysis suggests that there is much common ground in the past and present regarding the construction of gendered identity.

At this point, it is important to note that friendship in the eighteenth century had a different connotation than it does today. Although the term “friends” included the affectionate relationship between individuals as is now most commonly understood, it also referred to a much wider range of relationships in the eighteenth century. As Naomi Tadmor explains , “In the eighteenth century, the term ‘friend’ had a plurality of meanings that spanned kinship ties, sentimental relationships, economic ties, occupational connections, intellectual and spiritual attachments, sociable networks, and political alliances” (167). As such, rather than signifying a single specific type of relationship, “a spectrum of relationships [were] designated in the eighteenth century as ‘friendship’” (Tadmor 167). Understanding friendship in this sense, Winch’s argument about the less visible, but nevertheless strategic and political aspects of female friendship today was much more visible and widely accepted as such in the past. In other words, in contrast to the seemingly more intimate and personal relationships between friends in the present, eighteenth-century associations of the term itself implied a more complex interaction between the individual and the community; “Friendship relationships,” asserts Tadmor, “were major social relationships in eighteenth-century England” (171). In this sense, the political significance that was implied in the spectrum of friendship in the eighteenth-century context has continued on until today, albeit in a less apparent form.

Among this wide spectrum of friendships in the eighteenth century, friendships between women and their system of surveillance deserves particular attention because, as Amanda E. Herbert states, historians have often brushed away investigating the “construction and maintenance of early modern women’s social networks, and have largely ignored early modern women’s relationships with other women” despite the fact that “many women lived in largely ‘homosocial’ worlds” (1). Alone, women would read conduct books that were intended to “create a woman . . . who never stopped checking her behavior and thoughts against the standards of ideal womanhood. Once internalized, the rules of a conduct manual would create a completely self-regulating woman, who would always behave as if she were being observed even when she was alone” (Tague 22-23). These prescriptive guidelines, however, also emphasized social interaction as a requirement to be met: “The ability to relate to others, and especially to other women, was considered to be an essential component of this modern feminine identity” (Herbert 13). Herbert, moreover, writes that women were “taught to monitor themselves but were told simultaneously to monitor the actions, words, and attitudes of their female friends, to think carefully, constantly, and critically about the actions and behaviors of other women” (48); they were “reassured that to scrutinize the behaviors of their female friends was natural and desirable as well as rational and virtuous. Their personal papers attest that elite women did, in fact, practice this type of social surveillance” (48). The conflicting messages here which ask women to both relate through compassion and censure through surveillance seems to be the catalyst that initiates, or even encourages, the frenemy relationship between women and their network as a whole. As historians have discovered, in the eighteenth century, “many female-female interactions were marked by acrimony,” and women “fought with one another, slandered and censured the behavior of their female associates, and evaluated and criticized the bodies and moral characters of the women who surrounded them” (Herbert 4).

The clashing messages of compassion and censure in such conduct literature takes form in the frenemy relationships represented in fictional texts produced in the eighteenth century as well. Haywood’s novels, for example, often engage in examining this tense and precarious female friendship. Although Haywood is most commonly known as the prolific writer of amatory fiction that revolves around the passionate (and, more often than not, scandalous) romance between men and women, her interest in the wide spectrum of female relationships is consistently evident throughout her works. As Catherine Ingrassia states in her article “‘Queering’ Eliza Haywood,” “[Haywood’s] texts in multiple genres throughout the course of her career structurally and descriptively present same-sex relationships of varying degrees of intimacy” (9). This interest may have also been incited by the literary climate of the time, but Haywood’s well-known frenemy relationship with Martha Fowke Sansom early in her career may also have inspired her to contemplate and depict female frenemies in her novels.

In 1719, when Haywood was unsuccessful as an actress and was beginning her literary career, she became part of the “Hillarian Circle,” a literary coterie of both male and female writers that gathered around Aaron Hill. Poets Richard Savage and Martha Fowke were also part of this group and much has been speculated about the relationships and tensions among these four writers. One of the scandalous stories centers around the erotic triangle involving Haywood, Savage, and Fowke in which Haywood is framed as Savage’s shunned mistress and unwed mother of his child. However, Kathryn King points out that since not much about Haywood’s personal life is known, critics have often made conjectures inspired by a “desire to retrofit the pioneering novelist, playwright, actress, and journalist with a scandalous life” (“Savage Love” 723), and that Savage is misplaced as central to the two women’s rivalry: “The object of rivalry is not the ill-favored pimp but his charismatic friend Aaron Hill” (“Savage Love” 728). Hill seems to have been quite the popular figure for, as Christine Gerrard notes, “Many women found Hill irresistible” (67). In addition, “During the period 1720-8, Hill emerged as perhaps the most important, certainly the most ubiquitous, man of letters in London literary life” (Gerrard 62). According to King, Hill was also “a socially well-connected and culturally formidable figure, not to mention handsome, kindly, generous, charismatic, and genuinely devoted to the cultivation of new artistic talent” (“New Contexts for Early Novels” 264). Haywood and Fowke’s frenemy relationship, however, did not generate merely from competition for sexual desirability, but from literary aspirations as well: “Rather than romantic attachment or erotic longing, [Haywood’s verses on Hill] bespeak literary ambition, for in them Haywood attaches her efforts as a poet to the man who (as she tells it) spurred her on to feats of literary emulation” (“Savage Love” 732). Even so, King concedes that “the fact remains that Haywood does indeed stalk Sansom in print with a vindictive malice that certainly looks like sexual jealousy” (“Savage Love” 733). In the end, Haywood’s malicious portrait of Fowke as the sexually insatiable Gloatitia in Memoirs of a Certain Island Adjacent to the Kingdom of Utopia (1724) resulted in repulsing the Hillarians and for Hill to refer to Haywood as “the Unfair Author of the NEW UTOPIA” (qtd. in Gerrard 95). Haywood’s frenemy relationship with Fowke does indeed seem like a complex one in which the two women’s sexual desires and literary aspirations were intertwined.

Perhaps partially inspired by her frenemy relationship with Fowke, Haywood seems to have reflected on the complexities of friendships between women from early on in her career. Her earlier works certainly show toxic relationships between women, but neither is she blind to the more amicable and beneficial relationship that can arise between women. Read side-by-side, two of Haywood’s early novels written in the same year, The Masqueraders: Or Fatal Curiosity (1724) and The Surprise; or Constancy Rewarded (1724), particularly show how female friendship can be either toxic or beneficial. As Tiffany Potter points out in her introduction to the two novels, reading them together “offers the opportunity for a much clearer sense of the nuance and variation of Haywood’s first period so long dismissed as formulaic and repetitive” (4). Focusing on the relationship between two female friends, these two novels certainly present Haywood as an author with broader interests and insights.

In The Masqueraders: Or Fatal Curiosity, Haywood seems to depict the stereotypical frenemy relationship by illustrating the dangers of women sharing their intimate secrets–these secrets becoming the tools that generate envy, betrayal, and finally downfall. Dalinda is a stunningly beautiful widow and Philecta is less beautiful, but is more intelligent. Dalinda has a relatively long-term relationship with Dorimenus, but she makes the wrong decision of relating every detail of their relationship to Philecta:

Philecta, a young lady, on whose Wit, Generosity, and Good-nature [Dalinda] had an entire dependence, was the Person she made Choice of, to be interested with the dear burthen of this Secret; and while she related to her the particulars of her Happiness, felt in the delicious Representation a Pleasure, perhaps, not much inferior to that which the Reality afforded.—Having brought herself to make this Confidance, she no sooner parted from his Embraces, than she flew to her fair Friend, gave her the whole History of what had pass’d between them—repeated every tender Word he spoke . . . (73)

The language here is suggestive of intimacy and sensuality; Ingrassia asserts that this is an example of “[s}tructurally erotic friendships, formed by the oral transmission of narrative details of sexual encounters [that] populate Haywood’s work” (13). Dalinda is shown here to derive as much pleasure from narrating her story as when she actually experienced it. Potter argues, however, that Dalinda’s storytelling is proof of her vanity: “Dalinda requires that Philecta fantasize not about having Dorimenus, but about being Dalinda, and thus refuses her requests to observe an encounter with or to meet Dorimenus” (35). If what Potter contends is true, Dalinda’s intentions go terribly wrong, for Philecta “listen’d to her at first only with Compassion” (73), but soon she “began to envy the Happiness of her Friend” (73-74). As the novel’s full title suggests, Philecta then becomes so overwhelmed by her curiosity that she schemes to meet Dorimenus by herself, which only makes her fall in love with him and betray Dalinda. Soon becoming infatuated with Philecta, Dorimenus rejects Dalinda and thus enraged, Dalinda spreads word about Dorimenus and Philecta’s relationship to the whole town and irrevocably ruins Philecta’s reputation. By the end of the first book, Philecta has lost “her Virtue, her Reputation, and her Peace of Mind” (99); she is pregnant with Dorimenus’ child, but in the next book, he has ended his relationship with Philecta and soon marries another woman. It is telling that this is a novel about the properties of friendship for Dorimenus is merely “the objectified site of women’s sexual competition” (Potter 33). The sharing of secrets that was at first proof of Dalinda and Philecta’s friendship immediately becomes a vulnerability for Dalinda’s romantic relationship and for Philecta’s reputation. While Dalinda’s mistake was of revealing too much to her friend, she also recognizes contemptuous gossip as the most powerful weapon for revenge. In other words, Dalinda has misjudged the appropriate amount of secrets to share with Philecta, while knowing exactly how to destroy her by social censure.

In stark contrast to Dalinda and Philecta’s friend-turned-enemy relationship, Haywood also shows how compassionate friendship between women can achieve happy endings in The Surprise; or Constancy Rewarded. Written around the same time as The Masqueraders, it is indeed surprising how both novels depict women revealing secrets, but with very different results. Alinda has two suitors, Ellmour and Bellamant, but while favoring them amongst the others, she “felt not any of those violent Emotions which are the Characteristics of desire” (134). Upon seeing Bellamant, her friend Euphemia reveals her tragic history with Bellamant that ended with him leaving her before the wedding. Here, Alinda is portrayed as a very different character from either Dalinda or Philecta: “my dear Euphemia, I have for this time, put it out of my power to gratify that Inclination too many of our Sex have for blabbing everything that has the Appearance of a Secret” (136). Especially when comparing this novel to The Masqueraders, Haywood seems to be criticizing, through Alinda’s words, the tendency of women to lack compassion and to indulge in censorious gossip, which ultimately causes distressed women to suffer even more.

Haywood’s early interest in representing the complex dynamics between women seems to have persisted and developed throughout her career, for the opening of one of her later novels, The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless (1751), directly addresses this issue of compassion, or lack thereof, in relationships between women:

It was always my opinion that fewer women were undone by love, than vanity; and that those mistakes the sex are sometimes guilty of, proceed, for the most part, rather from inadvertence, than a vicious inclination. The ladies, however, I am sorry to observe, are apt to make too little allowances to each other on this score, and seem better pleased with an occasion to condemn, than to excuse; and it is not above one, in a great number than I will presume to mention, who, while she passes the severest censure on the conduct of her friend, will be at the trouble of taking a retrospect of her own. (27)

Beginning the novel with such commentary encourages the readers to take on a more compassionate stance in the judgement of its heroine. At the same time, this passage asserts how the “ladies” have assimilated into the culture of policing and harshly judging one another; they are “pleased with an occasion to condemn, than excuse” and “pas[s] the severest censure on the conduct of her friend.” This seems to imply that a sense of empowerment, however false, rises from condemning one of their sex. It also suggests that when a woman is assimilated into a culture in which her reputation, the public form of virtue, is often measured and rated against each other, women’s friendship attains the characteristic of frenemies.

In her final novel The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy (1753), Haywood extends her examination of female friendships, specifically placing the heroine in the position to condemn or excuse the conduct of other women. While Haywood’s earlier novels seem to focus more on the individual friendships between women, this novel pays more attention to women within a female community. This last Haywood novel seems to be curiously understudied in her oeuvre and is generally known as a moral and didactic novel which can be read as proof of the author’s reform from the author of amatory to moral, didactic fiction. John Richetti even states that Haywood is renouncing “her own version of romance and sexual sensationalism” (xxiii), but that does not seem to be the case; the many anecdotes of the characters’ experiences are direct echoes of Haywood’s earlier works. As King asserts, “the Haywood of the forties and fifties [should be regarded] as matured, not reformed” and should be appreciated as “an evolving deliberate literary artist every bit as interested as Richardson or Fielding, say, in expanding the ethical possibilities of the novel—and a great deal more interested than either in mapping the contours of female growth” (“Strange Surprising Adventures” 216). Haywood’s last novel certainly seems to focus on “the contours of female growth,” specifically in relation to the female network the heroine experiences first-hand.

As can be guessed from the title, The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy is the story of Jemmy and Jenny, distant cousins who were brought up by their parents with the hopes of getting the two married. When both of them become orphans, though well-provided for and come of age, Jenny suggests that they should postpone their marriage until they navigate the world further and discover what constitutes happiness in marriage. The effect of this proposal is that Jemmy and Jenny are separated from each other for the most part of the novel; while Jemmy enjoys the pleasure of a rake, Jenny mostly stays with her female companions (sisters Lady Speck and Miss Wingman) in Bath before entering her union with Jemmy.

Haywood’s choice of sending Jenny to Bath with her two friends seems to be a meditated choice that directs attention to the significance of female friendship. Bath was in itself a space where active female socializing happened in the eighteenth century. According to Herbert, spa cities such as Bath were extremely popular in the eighteenth century and these spas, “in addition to being gathering places for people of both sexes, were sites of same-sex sociability, as both women and men undertook distinct activities during their sojourns” (117) that “served as crucial sites for gendered identity creation” (118). “For many women,” writes Herbert, “spending time in female company rather than with men was a critical component of the experience of visiting the spa, both in the water and out of it” (124). In this sense, although much of the narrative presents Jenny and her two female companions in the company of other men, the location itself is suggestive of a heavy focus on homosocial interactions. Jenny also recognizes that “[h]er intimacy with Lady Speck and Miss Wingman was very much increased since she had been at Bath with them, by the participation they had in her secrets, and she in theirs” (347).

Furthermore, as Herbert asserts, “Spa cities were places where the female population was larger than the male population, and female residents of spa cities were socioeconomically diverse and widely visible” (127). This setting, therefore, also enables Jenny and her company to encounter and hear the three self-told narratives by three distressed young women. These three women are Mrs. M, the Fair Stranger, and Sophia. Despite their different stories, these women, as Karen Cajka points out, “share the misfortune of being completely unprotected” (48). Mrs. M, who is married to a wealthy man, decides to make her husband jealous by committing adultery with the libertine Celandine. When her relationship with Celandine is discovered, she becomes dependent on him and then stalks him to Bath. Upon seeing Celandine forcing himself on Jenny in the garden, Mrs. M mistakes Jenny as Celandine’s lover and tries to attack her. This act sets the scene for her to tell her story to Jenny and company. Not long after, the company meets the Fair Stranger who has run away in order to avoid marrying a much older man. In her story, her father threatens her that if she does not marry the older man, he will cut all ties with her: “Then never think I am your father;—think rather of being an utter alien,—an outcast from my name and family” (185). Sophia, Jenny’s school friend, whose unfortunate narrative enters near the end of the novel, tells her story only to Jenny. Attracted to the handsome army officer Willmore, Sophia lends him money so that he can buy a commission and marry her. Before they get married, however, Willmore takes Sophia to a brothel disguised as his aunt’s home and tries to rape her. After escaping from the brothel, Sophia tries to get her money back by meeting several lawyers, but her attempts are unsuccessful and only soil her reputation. Cajka convincingly argues that “[n]one of the three [women] has a mother to guide her, and Sophia and Mrs. M are completely orphaned. Further, older friends and relatives who might offer the women material or moral protection fail to provide it, thus leaving the women to make their own uninformed and often dangerously precipitate decisions” (48).

Haywood’s particular interest in exploring the frenemy dynamics between women is strongly present in these three narratives. All of their stories include the figure of a frenemy who, in diverse ways, contributes to Mrs. M, the Fair Stranger, and Sophia’s respective unfortunate events. In the case of Mrs. M, “a female friend of more years and experience” (119) encourages her to put on coquettish airs before Celandine in order to incite jealousy in her husband. However, despite this bad advice, what seems to have pained Mrs M more is the presence of “an elderly woman, a relation of [her] husband’s” (122) who “with a stern voice and countenance told [her], that she was sent by him to take care of his family; and that [Mrs. M] must immediately go out of the house” (122). What hurts Mrs. M is not only the message from her husband, but the woman’s coldness in conveying it to her: “This message, and the manner in which it was deliver’d, stung [her] to the very soul” (122). In the case of the Fair Stranger, when she is forced to marry the older man she does not love, she laments her own misjudgment in seeking consolation from her sister, “who by the rule of nature should have pitied [her] distress, rather added to it by all the ways she could invent” (187). The Fair Stranger, furthermore, recognizes her sister as an accomplice to her father in her misfortune: “Indeed [my sister] never loved me, and I have reason to believe I owe great part of my father’s severity to her insinuations” (187). In the case of Sophia, Willmore lures her to the brothel by saying that he “had an aunt, an excellent good old lady” (326); when Willmore “said a great deal more in praise of these relations” (327), Sophia “was so much charmed with the character of [this] aunt [and her two young daughters] . . . that [she] almost longed to be with them” (327). Upon entering the brothel, Sophia is greeted by a “grave old gentlewoman whose appearance answered very well to the description Willmore had given of her” (327), but Sophia’s continued narrative shows that this was also an act on the old woman’s part, as she was complicit in Willmore’s scheme to take Sophia’s money. Although the old woman displays many acts of hospitality, when Sophia is almost raped by Willmore, “[the old woman] took Willmore by the arm, and drew him to a corner of the room, where they talked together for the space of several minutes” (333). Moreover, when Sophia mentions her intentions to make Willmore return the money he borrowed, the old woman suspiciously cries, “I am quite a stranger . . . [t]o all affairs between you; but I will go up directly and let him know what you say” (334) and immediately leaves her. As such, Mrs. M, the Fair Stranger, and Sophia’s narratives all feature women who they assumed would be friends, but actually proved to be enemies.

What is striking here is how these female “friends” become enemies by assimilating or contributing themselves to the judgments and plans controlled by men. Considering the long history of patriarchal control over gendered identity, the idea of male power controlling women may not be surprising; it is, however, significant that this hegemonic system can be seen even to affect the relationships between women as well. According to Winch, “Men in girlfriend culture are a foil to women’s own lack of power” and “the sphere of girlfriendship [is] where discontent over injustice and male power is redirected towards their bodies and the bodies of other women” (61). Winch further notes that “[t]he girlfriend gaze is a handmaiden to the male gaze. It is powerful because the handmaiden mocks and plays with the rules of patriarchy within the intimate space of a female cohort, while simultaneously being complicit in the enforcement of its power“(27-28). While Winch’s analysis focuses on women today evaluating the physical bodies of other women as an act of empowerment, the same surveillance seems to be happening in the eighteenth century regarding women’s virtue and reputation. It is, therefore, important to examine how acts of compassion and contempt between women intersect with patriarchy.

Even as Jenny and the company listen to Mrs. M and the Fair Stranger’s histories, a man is shown as trying to dictate and correct how the women should respond to these unfortunate narratives. When discovering Mrs. M swooning after her failed attack on Jenny, Mr. Lovegrove, Lady Speck’s suitor and one of Jenny’s company, cries, “Whatever she is, her figure, as well as the present condition she is in, seems to demand rather compassion than contempt” (116). Interestingly enough, the two sisters immediately engage in acts of “compassion” just like they are told: “On this Lady Speck and her sister ran to assist the charitable endeavor [Mr. Lovegrove] was making for [Mrs. M’s] recovery” (116). Jenny, however, “still kept at a good distance” (116), which may be natural considering that she was the intended victim of Mrs. M’s attack, but it could also be indicative of her nature and rationality to judge on her own rather than follow the judgment of others. Upon the appearance of the Fair Stranger, Mr. Lovegrove, “who had undertaken to be the speaker” (181) is again the one who begins the interrogation of the Fair Stranger’s identity; the word “judge” often appears in this section of the text, emphasizing the need to sentence the Fair Stranger as either guilty or innocent. When Lady Speck gives six guineas to the Fair Stranger, to which Jenny was “extremely scandalized at the meanness of the present” (197), Mr. Lovegrove, “who doubtless had his own reflections” (197), remedies the situation by purchasing a small snuffbox for ten guineas from the Fair Stranger and then returning it to her as a gift. Since, as Herbert writes, “Women of lower status could and did serve as a check on the behavior of elite women, especially when they felt that obligations of charity and pity had gone unfulfilled” (49), Mr. Lovegrove can be seen here to be correcting Lady Speck’s behavior. Jenny, however, who “did not think proper to discover her opinion of [the meanness of the present] at that time” (197), follows the Fair Stranger on her way out and secretly presents her with an extra five guineas. This action shows Jenny as a compassionate and autonomous agent in assisting other woman; she is also discreet so as not to insult Lady Speck in public.

Lady Speck, although her monetary contribution was viewed as uncharitable by Mr. Lovegrove and Jenny, nonetheless provides an additional service to the Fair Stranger. When hearing that the Fair Stranger needs a man and horse to travel, Lady Speck assures her that “[she] need not . . . be at the pains or expense of hiring a man and horse,” which was “joyfully accepted” (198). Interestingly, the narrator states that Mr. Lovegrove is at a loss to an answer when hearing the Fair Stranger’s lack of transportation. While particularly in Mrs. M’s case it is implied that the patriarchal perspective governs the way in which compassion or contempt is administered by and to women, in the case of the Fair Stranger, although the male figure seems to take control at first, the women can be seen actively to participate in assisting other women in distress.

Jenny is often outside of this patriarchal control when it comes to her reflections on the stories of other women. In the case of Mrs. M, Jenny does not immediately respond until she has evaluated the story herself. In the case of the Fair Stranger as well, she holds onto her own reflections and acts accordingly. Her private conversation with Sophia shows how Haywood has left this final narrative to be reflected on by Jenny alone. Jenny’s reflections throughout the novel offer an intriguing insight into how her perspective oscillates between compassion and contempt towards women. While Jenny’s reflection on the perils of the women she meets encourages readers to engage in both censure and sympathy, her final thoughts are sympathetic, for as Cajak argues, “Jenny’s compassionate interactions with unprotected women . . . remind readers that although they may be unable materially to protect one another from unscrupulous men and the strictures of patriarchal society, they also need not be complicit in their punishments” (56). Jenny’s reason for delaying her marriage to Jemmy is, as she tells him, because “[she] think[s] [they] ought to know a little more of the world and of [themselves] before [the] enter into serious matrimony” (27) and because they need “to learn, from the mistakes of others, how to regulate [their] own conduct and passions, so as not to be laugh’d at [themselves] for what [they] laugh at in” others (31). In contrast to the Jenny in the beginning who is ready to “laugh at” the mistakes of others, it is highly unlikely that Jenny would be doing so when the novel comes to an end. Possibly, Celandine’s forcing himself on her also made her realize that not all misfortunes can be easily blamed on women in society. It must be noted that it is in this very moment of Celandine’s assault that Mrs M, the first of the three distressed women, comes into the scene, and Jenny and her company judge whether to feel sympathetic or critical about her story. Through her encounters with other women and their secrets, she has realized that it is not only an individual woman’s mistakes but also her circumstances that may bring tragic consequences.

One other change in Jenny is how she has learned to hide certain stories from men. In the beginning, she lightheartedly sets out to share the stories of other men and women she hears with Jemmy. However, this practice diminishes soon, and she doesn’t tell Jemmy about Celandine’s sexual assault in detail. As the narrator writes, “Never had this young lady given a greater demonstration of her prudence, than in thus shadowing over, as much as truth would permit, the insolence of Celandine” (287). Although the narrator only says that this was due to Jenny’s concern for Jemmy in case he runs into Celandine, it also suggests that the story, once turned public, would impact her and Jemmy’s respective reputations. At the end of the novel, Jenny finally marries Jemmy since she “had now done enquiring into the follies and mistakes of her sex, as she had seen enough of both to know how to avoid them” (395). Right before this statement, however, Haywood draws attention back to female friendships by providing an anecdote of Miss Chit and Lady Fisk’s frenemy relationship: “Miss Chit had quarrel’d with her great friend Lady Fisk . . . the animosity of these fair rivals was arriv’d to such a height, that they made no scruple of betraying to the world all the failings each had been guilty of, and of which they had been mutually the confidants” (395). In this sense, the novel consistently shows and draws attention to the dynamics and influences of female friendships individually and as members of a broader community of women.

Although the idea that Haywood’s later fiction changed its tone due to the moral demands of the market still seems to be pervasive, Haywood (like Jenny, who is portrayed as an astute reader and researcher) can be seen to have developed into a more insightful author in her representations of the complex female networks characterized by their frenemy dynamics in eighteenth-century society. Her final novel, The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy, is an expression of her understanding of this network, especially since Haywood seems to have considered situating women within homosocial communities before her marriage as a matter of import. What this suggests is that in order to enter into a “happy” marriage, a woman needs to understand the frenemy dynamics between women first. Frenemy relationships within social networks become almost synonymous with the potential of being perceived with compassion or censure following the act of social surveillance. Haywood certainly advocates compassion. The frenemy dynamics between women can be seen to be borne from patriarchal order and to contribute to upholding it, resulting in women being quick to punish one another. What women need to understand, then, is how this dynamic works and to become more compassionate, rather than censorious. Today, too, this process of quick censure can be seen to happen through, for example, “slut-shaming,” which stems from “the traditional misogynist fear of the female libido” (Winch 5). Haywood’s message that the female community needs to lean toward compassion rather than contempt is as relevant to women today as it was in the eighteenth century.

Works Cited

Cajka, Karen. “The Unprotected Woman in Eliza Haywood’s The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy.” Masters of the Marketplace: British Women Novelists of the 1750s. Ed. Susan Carlile. Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh UP, 2011. 47-58.

Gerrard, Christine. Aaron Hill: The Muses’ Projector, 1685-1750. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.

Haywood, Eliza. The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy. Ed. John Richetti. Lexington, KY: UP of Kentucky, 2005.

—. The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless. Ed. Christine Blouch. Peterborough, ON: Broadview P, 1998.

—. The Masqueraders, or Fatal Curiosity & The Surprize, or Constancy Rewarded. Ed. Tiffany Potter. Toronto: U of Toronto UP, 2015.

Herbert, Amanda E. Female Alliances: Gender, Identity, and Friendship in Early Modern Britain. New Haven: Yale UP, 2014.

Ingrassia, Catherine. “‘Queering’ Eliza Haywood.” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 14.4 (2014): 9-24.

King, Kathryn R. “The Afterlife and Strange Surprising Adventures of Haywood’s Amatories (with Thoughts on Betsy Thoughtless).” Masters of the Marketplace: British Women Novelists of the 1750s. Ed. Susan Carlile. Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh UP 2011. 203-218.

—. “Eliza Haywood, Savage Love, and Biographical Uncertainty.” The Review of English Studies 59.242 (2008): 722-740.

—. “New Contexts for Early Novels by Women: The Case of Eliza Haywood, Aaron Hill, and the Hillarians, 1719-1725.” A Companion to the Eighteenth-Century English Novel and Culture. Ed. Paula R. Backscheider and Catherine Ingrassia. London: Blackwell, 2005. 261-275.

OED Online. Oxford: Oxford UP. Web. April 27. 2018.

Potter, Tiffany. “Introduction.” The Masqueraders, or Fatal Curiosity & The Surprize, or Constancy Rewarded, by Eliza Haywood. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2015. 3-59.

Richetti, John. “Introduction.” The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy, by Eliza Haywood. Lexington, KY: UP of Kentucky, 2005. vii-xxxv.

Tadmore, Naomi. Family and Friends in Eighteenth-Century England. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001.

Tague, Ingrid H. Women of Quality: Accepting and Contesting Ideals of Femininity in England, 1690-1760. Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2002.

Winch, Alison. Girlfriends and Postfeminist Sisterhood. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

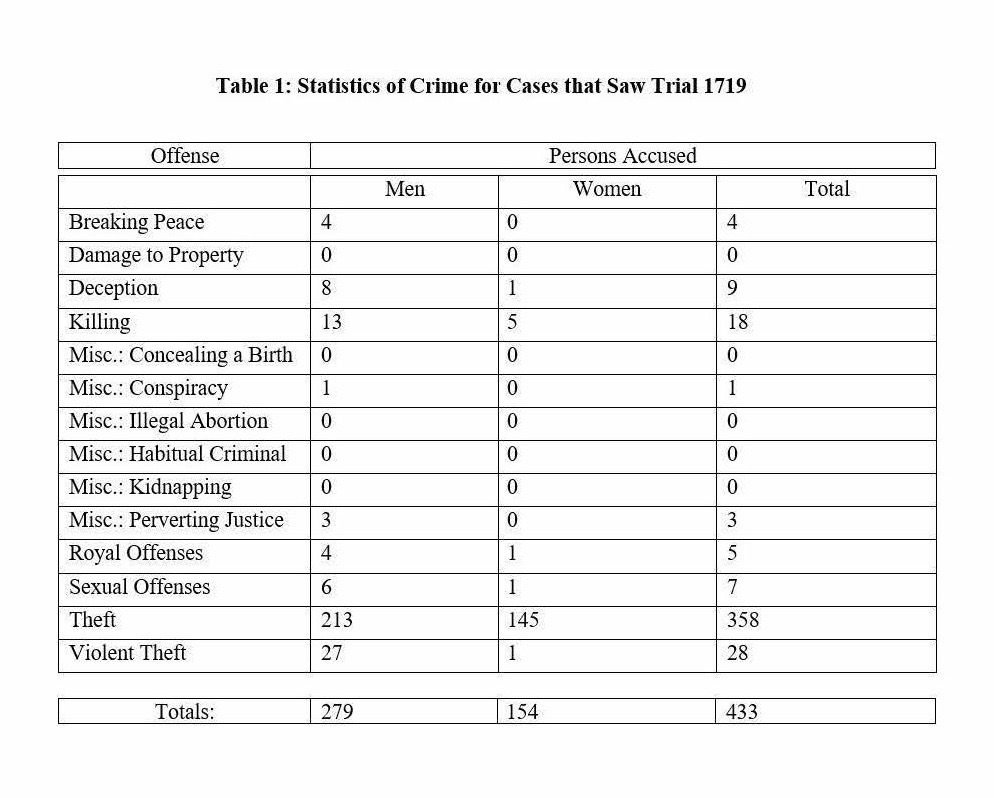

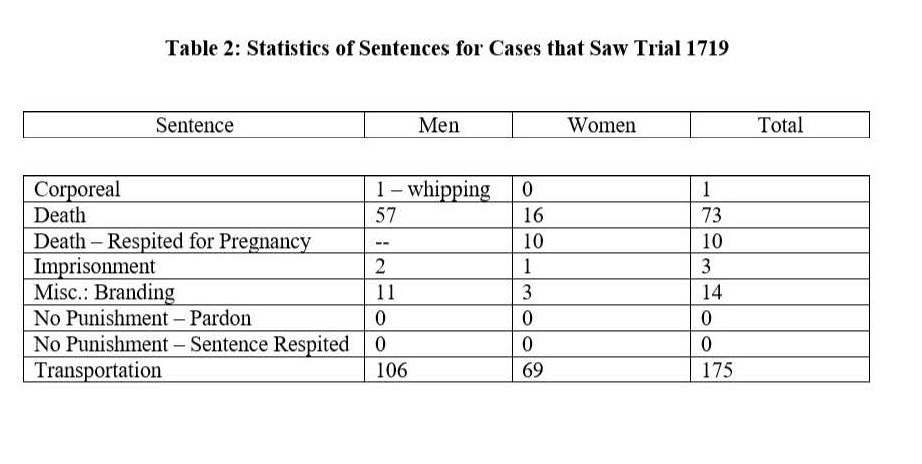

The statistics of crimes committed in the eighteenth century show that women stood trial far less than men. The Old Bailey Online reveals that from the 1690s to the 1740s, women accounted for 40% of defendants. This number significantly declined over the course of the eighteenth century, until reaching as low as 22% at the start of the nineteenth century (“Gender in the Proceedings”). In accordance, in examining the archives, I found that of the estimated 48,000 cases that saw trial from 1701 to 1800, about 69% consisted of male defendants, while 31% were female. Since 2019 marks the 300th anniversary of the publication of Love in Excess, I examined the 433 cases that went to trial in 1719: 154 involved female defendants, whereas 279 involved male defendants (Table 1). Although the majority of female defendants faced trials centered on killing and theft, their crimes were likely to be focused on their failure to adhere to expectations ascribed to their gender. These gendered crimes included infanticide, concealing a birth, unlawful abortion, theft, and coining (including keeping a brothel) (“Gender in the Proceedings”). Additionally, of the 154 females that stood trial in the year 1719, only 86 were found guilty, 10 of whom successfully received a respite for pregnancy (Table 2).

The statistics of crimes committed in the eighteenth century show that women stood trial far less than men. The Old Bailey Online reveals that from the 1690s to the 1740s, women accounted for 40% of defendants. This number significantly declined over the course of the eighteenth century, until reaching as low as 22% at the start of the nineteenth century (“Gender in the Proceedings”). In accordance, in examining the archives, I found that of the estimated 48,000 cases that saw trial from 1701 to 1800, about 69% consisted of male defendants, while 31% were female. Since 2019 marks the 300th anniversary of the publication of Love in Excess, I examined the 433 cases that went to trial in 1719: 154 involved female defendants, whereas 279 involved male defendants (Table 1). Although the majority of female defendants faced trials centered on killing and theft, their crimes were likely to be focused on their failure to adhere to expectations ascribed to their gender. These gendered crimes included infanticide, concealing a birth, unlawful abortion, theft, and coining (including keeping a brothel) (“Gender in the Proceedings”). Additionally, of the 154 females that stood trial in the year 1719, only 86 were found guilty, 10 of whom successfully received a respite for pregnancy (Table 2). One reason behind female theft could be the economic hardships that women encountered in London. Specifically, women’s wages were significantly lower than men’s and rarely guaranteed. Knowing this, it should be no surprise to suggest that women perhaps participated in various acts of theft to make ends meet. Of the 145 female theft cases in 1719, 15 involved shoplifting. Chloe Wigston-Smith discusses her examination of the Old Bailey Online proceedings in her book Women, Work and Clothes in the Eighteenth-Century Novel (2013) and notes that many stolen items involved textiles, garments, or accessories. She further explains how some women used their own clothes to assist in shoplifting (Wigston-Smith 95). Similarly, I found a case in 1719 of Mary Wilson, who was taken to trial for stealing four pairs of Worsted stockings. When she was apprehended, authorities found the stockings hidden “up her Coats” (“Mary Wilson”). Wilson was found guilty and sentenced to transportation. In addition to clothing, women would use accessories to assist in shoplifting. Urphane Mackhoule, for example, was found guilty in 1719 for stealing a pair of silver buckles. She did this by entering a shop and requesting some aniseed to distract the merchant. When the merchant turned his back, Mackhoule placed the buckles in her basket. She later confessed and was also sentenced to transportation (“Urphane Mackhoule”). Although the proceedings do not address specifically why Wilson and Mackhoule were stealing stockings and buckles, it is reasonable to infer that female acts of shoplifting could be rooted in an inability to afford the items they needed or desired due to economic hardships brought on by the gendered wage gap.

One reason behind female theft could be the economic hardships that women encountered in London. Specifically, women’s wages were significantly lower than men’s and rarely guaranteed. Knowing this, it should be no surprise to suggest that women perhaps participated in various acts of theft to make ends meet. Of the 145 female theft cases in 1719, 15 involved shoplifting. Chloe Wigston-Smith discusses her examination of the Old Bailey Online proceedings in her book Women, Work and Clothes in the Eighteenth-Century Novel (2013) and notes that many stolen items involved textiles, garments, or accessories. She further explains how some women used their own clothes to assist in shoplifting (Wigston-Smith 95). Similarly, I found a case in 1719 of Mary Wilson, who was taken to trial for stealing four pairs of Worsted stockings. When she was apprehended, authorities found the stockings hidden “up her Coats” (“Mary Wilson”). Wilson was found guilty and sentenced to transportation. In addition to clothing, women would use accessories to assist in shoplifting. Urphane Mackhoule, for example, was found guilty in 1719 for stealing a pair of silver buckles. She did this by entering a shop and requesting some aniseed to distract the merchant. When the merchant turned his back, Mackhoule placed the buckles in her basket. She later confessed and was also sentenced to transportation (“Urphane Mackhoule”). Although the proceedings do not address specifically why Wilson and Mackhoule were stealing stockings and buckles, it is reasonable to infer that female acts of shoplifting could be rooted in an inability to afford the items they needed or desired due to economic hardships brought on by the gendered wage gap.