A View of the South Front of the North Side of the Marshalsea Prison (1812), Unknown Artist after James Lewis, 1751–1820

When Melliora’s father dies in Eliza Haywood’s 1719 novel Love in Excess, she is entrusted into the care of D’elmont. Despite her sadness for her dying father, Melliora cannot help but fall for the Count the moment that her father turns her over to him. Haywood describes the complexity of Melliora’s feelings in this moment as follows: “she had just lost a dear and tender father, whose care was ever watchful for her . . . she had no other relation in the world to apply her self to for comfort . . . [but D’elmont] whom she found it dangerous to make use of, whom she knew it was a crime to love, yet could not help loving” (Haywood 88). The use of the word “crime” in this moment perfectly structures the tension within the narrative of Love in Excess. Haywood’s reconceptualization of love as a “crime” treats characters’ actions in pursuit of love as forms of crimes of passion. Furthermore, her criminality of love challenges gendered constructs of the eighteenth century. According to the Old Bailey Online, while men were viewed as the stronger sex, they were expected to be more intelligent, courageous, and determined. Alternatively, women were believed to be controlled by their emotions, leading to expectations of chastity, modesty, and compassion. Therefore, the expected faults of men were primarily acts of aggression (including violence and selfishness), whereas female faults centered on sins of the body (including lust and shrewishness) (“Gender in the Proceedings”). Sins of the body are exemplified in Haywood’s Love in Excess as women navigate their criminal affections. Examining the proceedings of real trials from the eighteenth century in relation to Haywood’s Love in Excess creates a space to address how constructs of gender in both real and imagined narratives determined criminal activity. Furthermore, this intersection between the real and imagined allows for a look at the ubiquity of widespread patriarchal institutions. Haywood’s criminal love demonstrates not only the economic and emotional struggles that women were facing but also how the lengths they went to fulfill their needs were met with a gendered response.

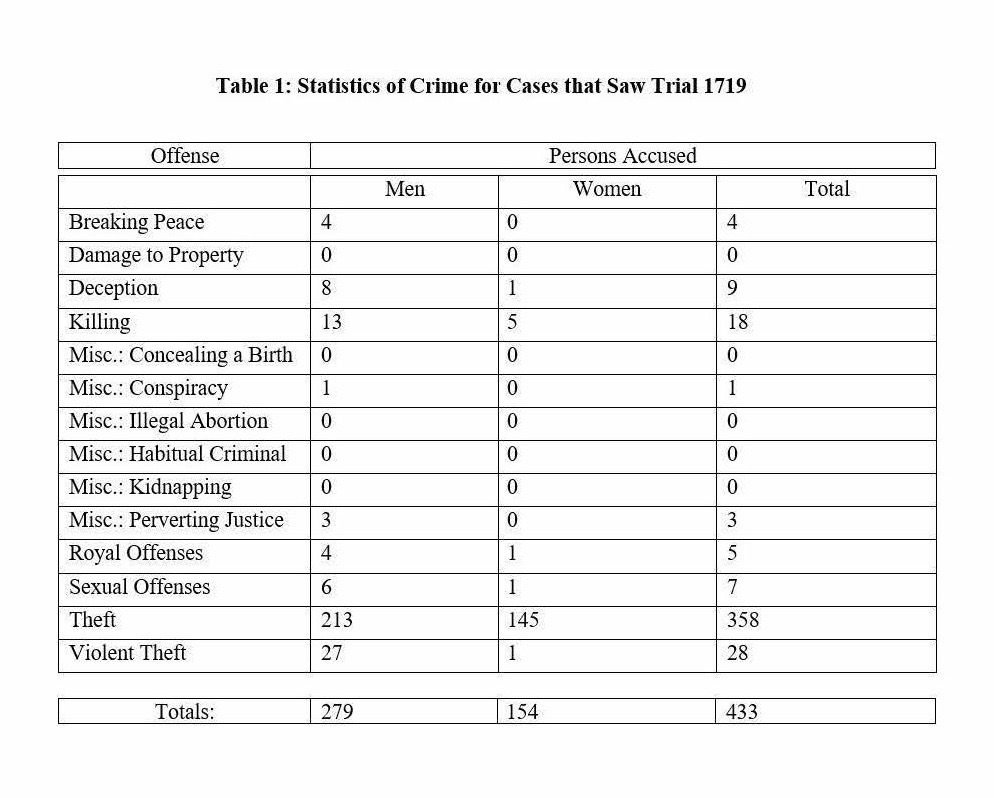

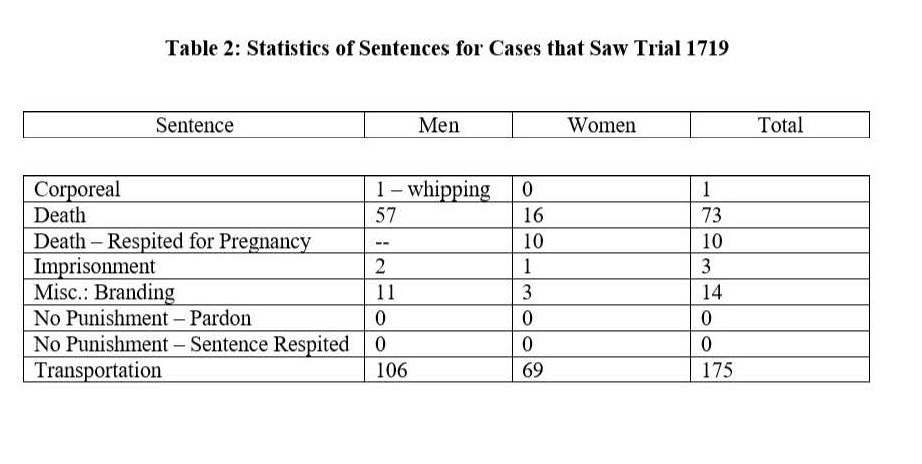

The statistics of crimes committed in the eighteenth century show that women stood trial far less than men. The Old Bailey Online reveals that from the 1690s to the 1740s, women accounted for 40% of defendants. This number significantly declined over the course of the eighteenth century, until reaching as low as 22% at the start of the nineteenth century (“Gender in the Proceedings”). In accordance, in examining the archives, I found that of the estimated 48,000 cases that saw trial from 1701 to 1800, about 69% consisted of male defendants, while 31% were female. Since 2019 marks the 300th anniversary of the publication of Love in Excess, I examined the 433 cases that went to trial in 1719: 154 involved female defendants, whereas 279 involved male defendants (Table 1). Although the majority of female defendants faced trials centered on killing and theft, their crimes were likely to be focused on their failure to adhere to expectations ascribed to their gender. These gendered crimes included infanticide, concealing a birth, unlawful abortion, theft, and coining (including keeping a brothel) (“Gender in the Proceedings”). Additionally, of the 154 females that stood trial in the year 1719, only 86 were found guilty, 10 of whom successfully received a respite for pregnancy (Table 2).

The statistics of crimes committed in the eighteenth century show that women stood trial far less than men. The Old Bailey Online reveals that from the 1690s to the 1740s, women accounted for 40% of defendants. This number significantly declined over the course of the eighteenth century, until reaching as low as 22% at the start of the nineteenth century (“Gender in the Proceedings”). In accordance, in examining the archives, I found that of the estimated 48,000 cases that saw trial from 1701 to 1800, about 69% consisted of male defendants, while 31% were female. Since 2019 marks the 300th anniversary of the publication of Love in Excess, I examined the 433 cases that went to trial in 1719: 154 involved female defendants, whereas 279 involved male defendants (Table 1). Although the majority of female defendants faced trials centered on killing and theft, their crimes were likely to be focused on their failure to adhere to expectations ascribed to their gender. These gendered crimes included infanticide, concealing a birth, unlawful abortion, theft, and coining (including keeping a brothel) (“Gender in the Proceedings”). Additionally, of the 154 females that stood trial in the year 1719, only 86 were found guilty, 10 of whom successfully received a respite for pregnancy (Table 2).

One reason behind female theft could be the economic hardships that women encountered in London. Specifically, women’s wages were significantly lower than men’s and rarely guaranteed. Knowing this, it should be no surprise to suggest that women perhaps participated in various acts of theft to make ends meet. Of the 145 female theft cases in 1719, 15 involved shoplifting. Chloe Wigston-Smith discusses her examination of the Old Bailey Online proceedings in her book Women, Work and Clothes in the Eighteenth-Century Novel (2013) and notes that many stolen items involved textiles, garments, or accessories. She further explains how some women used their own clothes to assist in shoplifting (Wigston-Smith 95). Similarly, I found a case in 1719 of Mary Wilson, who was taken to trial for stealing four pairs of Worsted stockings. When she was apprehended, authorities found the stockings hidden “up her Coats” (“Mary Wilson”). Wilson was found guilty and sentenced to transportation. In addition to clothing, women would use accessories to assist in shoplifting. Urphane Mackhoule, for example, was found guilty in 1719 for stealing a pair of silver buckles. She did this by entering a shop and requesting some aniseed to distract the merchant. When the merchant turned his back, Mackhoule placed the buckles in her basket. She later confessed and was also sentenced to transportation (“Urphane Mackhoule”). Although the proceedings do not address specifically why Wilson and Mackhoule were stealing stockings and buckles, it is reasonable to infer that female acts of shoplifting could be rooted in an inability to afford the items they needed or desired due to economic hardships brought on by the gendered wage gap.

One reason behind female theft could be the economic hardships that women encountered in London. Specifically, women’s wages were significantly lower than men’s and rarely guaranteed. Knowing this, it should be no surprise to suggest that women perhaps participated in various acts of theft to make ends meet. Of the 145 female theft cases in 1719, 15 involved shoplifting. Chloe Wigston-Smith discusses her examination of the Old Bailey Online proceedings in her book Women, Work and Clothes in the Eighteenth-Century Novel (2013) and notes that many stolen items involved textiles, garments, or accessories. She further explains how some women used their own clothes to assist in shoplifting (Wigston-Smith 95). Similarly, I found a case in 1719 of Mary Wilson, who was taken to trial for stealing four pairs of Worsted stockings. When she was apprehended, authorities found the stockings hidden “up her Coats” (“Mary Wilson”). Wilson was found guilty and sentenced to transportation. In addition to clothing, women would use accessories to assist in shoplifting. Urphane Mackhoule, for example, was found guilty in 1719 for stealing a pair of silver buckles. She did this by entering a shop and requesting some aniseed to distract the merchant. When the merchant turned his back, Mackhoule placed the buckles in her basket. She later confessed and was also sentenced to transportation (“Urphane Mackhoule”). Although the proceedings do not address specifically why Wilson and Mackhoule were stealing stockings and buckles, it is reasonable to infer that female acts of shoplifting could be rooted in an inability to afford the items they needed or desired due to economic hardships brought on by the gendered wage gap.

In addition to shoplifting, pocket-picking consisted of 11 crimes that women saw trial for in 1719. In the case of pocket-picking, Wigston-Smith explains that women “often worked together and that their schemes could involve between 2 and 7 women to distract the attention of victims” (Wigston-Smith 96). In a 1719 case, Mary Clarke was accused of following John Burcher into an alley. When Burcher was distracted by a “fight” between two women who had amassed a crowd, he claimed that Clarke slipped her hand in his pocket and stole seven shillings. It is unclear whether Clarke was working with the women or taking advantage of the situation, but she was eventually found not guilty (“Mary Clarke”). However, as Wigston-Smith notes, accusations of women pocket-picking can be further complicated by the number of cases that also involved prostitution. She notes that “pick-pockets were often equated with prostitutes, as both professions shared the same working space of the streets” (Wigston-Smith 96). The connection between prostitution and pocket-picking appeared so often that many judges would assume that men who claimed to be robbed in specific areas of London had actually been visiting a prostitute (96-97). Lastly, cases involving female pocket-picking could be fabricated when men purposefully wrongly accused women of theft in retaliation of rejected romantic advances. Some men even planted objects on their female rejectors to get them arrested (98). The number of fabricated accusations of female theft by men that saw trial further creates a gendered divide. In this moment the women are on trial twice: first, for the knowingly incorrect accusation of theft and, second, for being a woman who dared to reject a man.

Aside from various forms of theft and coining, women of the eighteenth century also often worked in the streets of London by singing ballads. Women flooded the ballad profession to use their voices to make money. Tim Fulford examines how the increase in the number of poor women can be attributed to the number of deaths of soldiers in Europe, America, the West Indies, and India, as well as the growth of London as a space of promise of commerce that drew these women in from the country (Fulford 313). Additionally, Branford P. Millar has described these women as often elderly and “tattered,” and Paula McDowell explains that they could sometimes be disabled or blind (Miller 129, McDowell 175). Ballad singers would sing loudly in the streets, often encouraging passersby to purchase print copies. Female involvement in ballad-singing not only provided women with some economic support but also a space for women to express their emotional responses to governmental structures through veiled lyrics. While ballads could contain the news or bawdy jokes, the ones that focused on social and political issues often resulted in arrest. Ballads were believed to be dangerous because they could stir up nationalist pride or feelings of unrest. Much of the information that we have of these female ballad-singers comes from records of their time in and out of jails and correction houses (McDowell 156). Elizabeth Smith, for example, was arrested for selling “The Highland Lasses Wish,” a Jacobite ballad that praised James Francis Edward, the Old Pretender. A 1719 search of the English Broadside Ballad Archive yields a ballad about the Lady Arabella Stuart called “The True Lovers Knot United,” which also disguises Jacobite sentiment through the story of Arabella’s unsuccessful elopement. These political ballads were, as McDowell describes, a “genre of ‘the people,’” but they also provided women with a means of money that could lead to legal danger.

While no characters are arrested in Love in Excess, Haywood’s conceptualization of criminal love shapes character behavior as crimes of passion. Ultimately, “crimes of passion” often refer to violent criminal acts inspired by a sudden strong emotional response. Although we stereotypically expect that strong response to be anger or hatred, it is possible to consider intense love as fuel for impulsive actions. Haywood’s reflection of eighteenth-century gender expectations within Love in Excess further examines changes in the construct of gender, as well as how the different genders hold power.

Similar to female ballad-singers, the written word is a powerful tool for expressing emotional unrest in Love in Excess. The novel opens with a description of Alovysa as “[suffering] her self to be agitated almost to madness between the two extremes of love and indignation” (Haywood 39). The use of “madness” lends weight to how passionate emotions ultimately consume Alovysa. Her obsession with D’elmont not only leads to her “rival” Amena’s life-long banishment to a monastery but also a lack of trust in her marriage, emotional suffering, and her untimely death. Alovysa uses her skills in writing and speaking to act on her passion. For example, when she realizes that D’elmont is pursuing Amena, Alovysa does not hesitate to write to him anonymously: “you cannot without a manifest contradiction to its will, and an irreparable injury to your self, make a present of that heart to Amena, when one, of at least an equal beauty, and far superior in every other consideration, would sacrifice all to purchase the glorious trophy” (45). Her strategic choice of placing D’elmont as a “trophy” flatters him as he realizes that he has more than one admirer. Furthermore, despite being close friends with Amena, Alovysa does not consider whether her actions will hurt Amena when she writes that she believes herself to be “far superior.” Tiffany Potter has observed that “Haywood undergoes a process of mastering this language of passion and claiming it for women as a creative, powerful, production value” (Potter 171). Alovysa’s clever turns of phrase in her anonymous letters allow her to manipulate the situation to secure her ultimate desires. Her willingness to do what she believes to be necessary in that moment–including sacrificing the wellbeing of her friend–assists in fulfilling her emotional needs. Potter investigates Alovysa’s cunning use of language to act on her passion through an understanding of knowledge as power. In the scene between Alovysa and the Baron, she is seeking information that only the Baron can tell her, while he wants sexual consent. Potter notes that Alovysa’s “agency here comes from the ability she is granted by Haywood to empower herself through playing both sides of her culture’s gendered constructions of language as she uses the language of desire, seduction, and adultery” (171-172). Alovysa’s use of written and spoken language allows her to gain the information and future she desires. Despite the emotional consequences of her actions, her use of language demonstrates her strength and willingness to act on her love for D’elmont.

Haywood’s discussion of crimes of passion further addresses the gender divide in the treatment of rejection and sins of the body through Melantha and Ciamara. The two women cannot physically restrain themselves from acting on their lust for D’elmont. At first Melantha tries to pursue the Count. However, after overhearing a conversation between the Count and her brother, Melantha becomes uneasy. She knows of her brother’s feelings for Alovysa, but the new information of the Count’s love for Melliora leads to her frustration with the men’s behavior. However, Melantha does not become dissuaded by this realization. Instead, she uses this information to her advantage to trick D’elmont to sleep with her and become pregnant. Rather than perform her gender as perhaps expected, she decides to take what she desires. When her crime of seduction is revealed, she is referred to by her brother as “that wicked woman” and as “deceitful” (Haywood 144). He is further angered by her “scandal” as well as what he sees as the betrayal of the family name, and he threatens to “stab [her] here in this scene of guilt,” an act prevented by D’elmont (144). Although Melantha is frightened that her brother will follow through on the threat, she argues: “neither am I guilty of any crime. I was vext indeed to be made a property of, and changed beds with Melliora for a little innocent revenge; for I always designed to discover my self to the Count time enough to prevent mischief” (145). Her word choice of “revenge” implies that she has become angered by the way that the men have been treating her. Melantha takes control of what power she can have through the use of her body. Yet, while it is perhaps socially accepted that the men pursue women how they please, the gendered response to a woman acting on her desire is a reaction asserting that she is something like a criminal.

In comparison to Melantha, Ciamara’s seduction not only fails but also further exacerbates the difference in gendered sins of the body. Ciamara tries to act on her lust for D’elmont by disrobing for him, kissing him, and guiding his hands to her body, all to persuade him to be with her (225). Unfortunately, for Ciamara, D’elmont is not convinced. However, before rejecting Ciamara, he takes a moment to enjoy her body. His actions are explained away as follows: “he was still a man! and, ‘tis not to be thought strange if to the force of such united temptations, nature and modesty a little yielded . . . her behavior having extinguished all his respect, he gave his hands and eyes a full enjoyment of all those charms” (225). This acceptance of D’elmont’s behavior is a stark difference from earlier in the novel, when he struggled to express the pain of his passion for Melliora. Multiple instances depict D’elmont as attempting physically to force himself onto Melliora, and these acts drive her to prevent their physical connection by stuffing the lock of her bedroom with torn pieces of her corset. Yet, in comparison to Ciamara, while it is inappropriate for a woman physically to act on her desires, the novel shows that it is ostensibly fully understandable for a man to do so.

Crime in eighteenth-century England was often understood to be driven by specific traits attributed to men and women. While men were expected physically to act on their aggression and desires, women responded to threats to their emotional and physical needs. Female crime in the eighteenth century was thoroughly addressed by popular fiction writers to much acclaim. Haywood’s criminalization of love makes way for a larger examination of patriarchal institutions. Her use of the written word as a means to establish control and her discussion of the unequal treatment of rejection and seduction show how gender expectations shaped responses to how individuals adhered or disrupted gender performance.

Works Cited

Fulford, Tim. “Fallen Ladies and Cruel Mothers: Ballad Singers and Ballad Heroines in the Eighteenth Century.” The Eighteenth Century 47.2 (2006): 309-329.

“Gender in the Proceedings.” Old Bailey Online. https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/static/Gender.jsp. Accessed 15 March 2019.

Haywood, Eliza. Love in Excess. Ed. David Oakleaf. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2000.

“Mary Clarke.” Old Bailey Online. https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17190408-2-off9&div=t17190408-2#highlight. Accessed 9 April 2019.

“Mary Wilson.” Old Bailey Online. https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17190408-30-off151&div=t17190408-30#highlight. Accessed 9 April 2019.

McDowell, Paula. “‘The Manufacture and Lingua-facture of Ballad-Making’: Broadside Ballads in Long Eighteenth-Century Ballad Discourse.” The Eighteenth Century 47.2 (2006): 151-178.

Miller, Branford P. “Eighteenth-Century Views of the Ballad.” Western Folklore 9.2 (1950): 124-135.

Potter, Tiffany. “The Language of Feminised Sexuality: Gendered Voice in Eliza Haywood’s Love in Excess and Fantomina.” Women’s Writing 10.1 (2003): 169-186.

Smith, Chloe Wigston. Women, Work, and Clothes in the Eighteenth-Century Novel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

“The Lovers Knot United.” English Broadside Ballad Archive. http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/32691/xml. Accessed 20 April 2019.

“Urphane Mackhoule.” Old Bailey Online. https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17190708-18-off93&div=t17190708-18#highlight. Accessed 9 April 2019.

The Boy Gangs of London

The prevalence of boy gangs on London streets has been famously preserved for us in literature by Daniel Defoe’s 1722 depiction of bands of roving boys and by Charles Dickens’s 1838 creation of Fagin’s network of pickpockets in Oliver Twist. But what of the real boy gangs from the period that caught the attention of these novelists? Where are they childlike? Or hardened adult-like criminals? This is the story of one such gang operating in eighteenth-century London.

She-Pirates: Early Eighteenth-Century Fantasy and Reality

“The Tryals of Captain John Rackam and Other Pirates” provides a vivid portrayal of she-pirates Mary Read and Anne Bonny as crossdressing women seafarers.

“No less than High Treason”: Libel and Sensationalism in the Careers of Jacobite Periodicalists George Flint and Isaac Dalton

The early eighteenth-century British press was a hotbed for propaganda wars: in the midst of the Succession Crisis, both Whig and Tory writers in London kept their fingers on the pulse of foreign affairs, war, and national politics.