The Crown (2017); Photo Credit: Alex Bailey, Netflix

With the premier of the second season of The Crown (2017), Netflix’s extravagant costume drama about Elizabeth II, the show has again occasioned debate among media critics and British historians. Everyone seems to agree that the acting, the settings, the lavish decor, and the meticulously detailed period clothing are all enthralling, but this is also the problem: according to Sonia Sodha, the show “may be good fun, but it’s not always good history” (The Guardian Online). Peggy Noonan admonishes The Crown for its “cheap historical mindlessness,” for taking extreme liberties with the private lives and intimate relationships of ministers at a time when so-called fake news has undermined truth in politics. In other words, the show’s writers and creators adventure to invent what they cannot possibly know. “In its treatment of history,” she claims, “there’s a deep clueless carelessness” (The Wall Street Journal Online).

Furthermore, academic historians of Britain and the independent nations that were part of the former British Empire criticize the show for glossing over brutal aspects of the imperial and industrial pasts. Kenya, Ghana, Malaya, New Guinea, and Tonga are reimagined as playgrounds for patrician globetrotters. The complexities of postcolonial politics are neglected; Southeast Asia and the South Pacific are problematically portrayed as spaces of exotic sexual spectacle for the white male colonial gaze. Viewers are offered a kind of Bildungsroman narrative about a reluctant but responsible queen coming into her own as wife, mother, and sovereign. We are asked to “sympathize with aristocrats and an unelected head of state,” Sam Wetherell writes, “The endurance of the monarchy in Britain is an open political question, but it goes unasked in The Crown” (Perspectives).

While I want to echo Rebecca Rideal’s recent argument that the show is fiction—it does not claim to be “real” history—and therefore it should be evaluated as drama, here I also want to suggest that it is actually doing something much more compelling in its engagement with historical evidence and narrative (New Statesman). The Crown, I think, should be understood as a secret history of monarchy. Secret history is a revisionist mode of historical writing that became fashionable in the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries in England, at a particular moment when popular anxieties about the lack of truth in partisan politics were at a crescendo. Analyzing it as such reveals that the show’s central question is precisely the one that Wetherell claims it fails to ask: How do we account for the affective appeal and almost perverse persistence of the British royal family in a world where, as Lord Altrincham reminds the queen in the sixth episode of season two, “republics are the rule and monarchies are very much the exception”?

With the rapid expansion of the ephemeral press in England following the end of pre-publication censorship in the late seventeenth century, the private lives of kings, queens, and other royal subjects became increasingly open to public representation and debate. One group of texts that dealt explicitly with issues of regal privacy, state secrets, and the domestic politics of royalty were secret histories of the crown. As the literary historian Rebecca Bullard contends in her book The Politics of Disclosure, 1674-1725: Secret History Narratives (2009), these texts challenged authorized accounts of the recent political past by exposing the private lives of ministers and monarchs to public scrutiny. They originated as a genre of writing popular with Whig authors and audiences: they reflected contemporary concerns that there were plots afoot to introduce absolutism and undermine political liberties within Britain, and they aimed to disclose conspiracies by teaching readers how to see through political deceit. Secret historians dramatized questions of truth in politics and media, encouraging audiences to adopt a skeptical stance toward print and political culture, often claiming to disclose hidden “facts” about the past that were, nonetheless, dubious. [1] After the 1688 Revolution, most secret historians focused their efforts on the revelation of political and sexual intrigue under the later Stuart kings, Charles II and James II, as well as France’s Louis XIV. Such texts, Michael McKeon argues, disrupted absolutism by publicizing the designs and misdeeds of monarchs. [2]

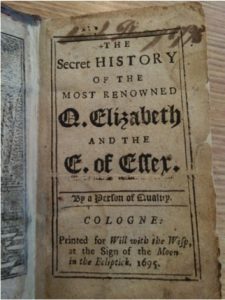

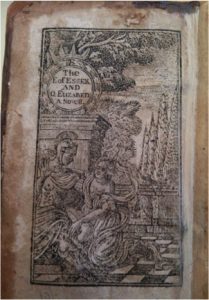

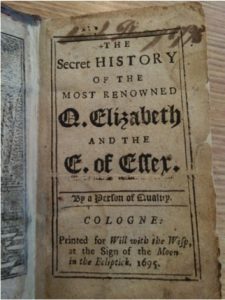

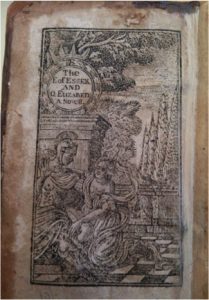

Other secret histories, however, do not fit this pattern: they are not overly partisan and they aim to allow readers access to the affective lives of royal figures even while their narrative structures reinforce the implausibility of their claims. These are the secret histories of Queen Elizabeth–the first, not the second. In 1680 The Secret History of Q. Elizabeth and the E. of Essex was anonymously printed in London, while The Secret History of the Duke of Alancon and Q. Elizabeth was first published in 1691. [3] Both continued to be widely reprinted in cheap editions across the eighteenth century, and the accounts they offered were reimagined in chapbook romances, plays, and operatic songs.

Other secret histories, however, do not fit this pattern: they are not overly partisan and they aim to allow readers access to the affective lives of royal figures even while their narrative structures reinforce the implausibility of their claims. These are the secret histories of Queen Elizabeth–the first, not the second. In 1680 The Secret History of Q. Elizabeth and the E. of Essex was anonymously printed in London, while The Secret History of the Duke of Alancon and Q. Elizabeth was first published in 1691. [3] Both continued to be widely reprinted in cheap editions across the eighteenth century, and the accounts they offered were reimagined in chapbook romances, plays, and operatic songs.

Both books call into question the celebrated history of Elizabeth’s reign and her status as an exemplar of Protestant queenship. The Secret History of Elizabeth casts the queen as exceptional but amorous, ruled by her love for Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, reinterpreting his rise, rebellion, and subsequent execution in 1601 as a consequence of the queen’s jealousy and manipulation by courtiers. In The Duke of Alançon, the marriage negotiations that took place between Elizabeth and the French prince in the late 1570s are reimagined to depict the queen as a power-hungry ruler whose love of independence leads her to reject all possible suitors and murder a made-up member of the royal family. Inexpensive and widely available, these stories perhaps invited middling readers to compare themselves favorably to Elizabeth.

Both books call into question the celebrated history of Elizabeth’s reign and her status as an exemplar of Protestant queenship. The Secret History of Elizabeth casts the queen as exceptional but amorous, ruled by her love for Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, reinterpreting his rise, rebellion, and subsequent execution in 1601 as a consequence of the queen’s jealousy and manipulation by courtiers. In The Duke of Alançon, the marriage negotiations that took place between Elizabeth and the French prince in the late 1570s are reimagined to depict the queen as a power-hungry ruler whose love of independence leads her to reject all possible suitors and murder a made-up member of the royal family. Inexpensive and widely available, these stories perhaps invited middling readers to compare themselves favorably to Elizabeth.

But, more importantly, the books commoditize the representation of Elizabeth’s personal life in an attempt to appeal to a public that increasingly desired personal access to and connection with celebrated royal figures. Their plots hinge upon the conflicts between queenship, love, and marriage, and they raise questions about how to distinguish between true affection and artifice, and about the kinds of authority the queen must yield to her husband if she marries. For instance, in The Secret History of Elizabeth, readers are privy to implausible conversations that take place between the queen and the Countess of Nottingham, to whom she divulges her secrets in a long narrative that takes up almost the entire first half of the novel. “You do not yet know Me, the Force I have long put upon My Self, hath made you think with the rest of the World, that the Height of my Spirit, hath raised Me above the Infirmities of Nature; and the Greatness of my Thoughts, secur’d Me from the troubles of Life,” the queen declares, “But, Alas! poor Elizabeth is a Slave to Her Weakness” (4). Her weakness, of course, is love. Similarly, after the French prince proposes to the queen in The Secret History of the Duke of Alançon, the narrator describes that she “began to tremble at the prospect of her condition to which she saw herself reduced, not unlike a Person who unexpectedly finds himself upon the brink of a Precipice” (40-41). At other moments, Alançon has an extended debate with a rival lover about the division of authority in marriage, about whether a husband should be his “Wife’s slave” or her “Tyrant” (47).

These books therefore reach into the domestic realm. They feign to represent the emotional lives of royal subjects in an invitation for readers to work through their own ideas about love and marriage through the sensational history of a queen—an extraordinary but nonetheless ordinary woman. The monarchy is here cemented into the affective history of the family, made central to conversations about emerging ideals of companionate marriage. These texts never claim to be true histories, nor were they seen as such. As one anonymous critic of secret history alleged in 1691, such books were mere romances, full of malice and forgery, contrived to snare “young Gentlemen and Ladies, who are addicted to such kind of Foolish Toys.” [4] Thus, much like other criticism of early novels, secret histories were thought to cause a kind of reading addiction among overly credulous readers, not for the revelation of political plots but for their false and morally suspect content, especially dangerous given their low cost.

The Crown, like the secret histories of Elizabeth that I have been discussing, draws attention to the contradictions between the public image and the private reality of queenship, and in so doing it highlights the enduring sway of emotion in contemporary politics. Much of the series focuses on the struggles within the royal family and tensions within the royal bedchamber. “What kind of marriage is this? What kind of family?,” Prince Phillip, Duke of Edinburgh demands of the queen after she reveals that she will retain her own surname in season one. The new season ends with a contrite Philip confronting a heavily pregnant Elizabeth as she hides away at Balmoral from the unfolding Profumo Affair, which threatens to engulf the prince. “We both know that marriage is a challenge, under any circumstances,” the queen states as the prince moves to rest his head in her lap, before the show suddenly cuts to her giving birth to Prince Edward. No witnesses, aside from viewers, are present at these intimate moments when sovereignty and conjugality collide. Rather than asking us to believe that these conversations actually happened, the show instead spotlights the ways in which the English royal household remains a space for the popular negotiation of domesticity and the affective bonds of the family. By anxiously condemning The Crown for lying and for misleading viewers who are thought to primarily get their history through popular culture, we replicate the same snobbish discourses with which eighteenth-century critics blasted secret historians: audiences are credulous, we worry, and they mistake the spectacle of romance for the truth of history. This attitude seems patronizing at best.

Finally, seeing The Crown as a secret history of monarchy allows us to appreciate how the show self-consciously calls attention to the role of media in the cultural nostalgia of English royalism. The writers repeatedly point out that the magic of regality is a commodity, delicately manufactured through public audiences, radio addresses, and, since the late 1950s, television broadcasts. Elizabeth’s coronation is an exercise in “Smoke and Mirrors,” the title of that particular episode declares, and we follow the camera lens as it reveals (and shields) the spectacle at Westminster Abbey. In the new season, Lord Altrincham criticizes the clipped tone and remoteness of the crown, quoting no less than the Victorian journalist Walter Bagehot’s The English Constitution (1865-67). Bagehot emphasized the constitutional role of monarchy as a kind of innocuous but vital entertainment for the masses. He attributed the sentimental appeal of royal figures to their celebrity status as the public face of the government, allowing subjects to form intimate attachments with individuals they would never meet in real life. “A royal family sweetens politics by the seasonable addition of nice and pretty events,” he wrote, “It introduces irrelevant facts into the business of government, but they are facts which speak to ‘men’s bosoms’ and employ their thoughts” [5]. By exploring how sovereignty is staged for public consumption, by using theatrical drama to unmask royalism as mere theater, and by probing the gap between the public history and fictionalized private lives of Elizabeth II, The Crown presses audiences to consider the political endurance of English monarchy.

Notes:

[1] Rebecca Bullard, The Politics of Disclosure, 1674-1725: Secret History Narratives (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2009). See also Rebecca Bullard and Rachel Carnell, eds. The Secret History in Literature, 1660-1820 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

[2] Michael McKeon, The Secret History of Domesticity: Public, Private, and the Division of Knowledge (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005).

[3] Anon., The Secret History of the Most Renowned Q. Elizabeth and the E. of Essex. By a Person of Quality (Cologne: Printed for the Will of the Wisp, at the Sign of the Moon in the Ecliptick, 1681); Anon., The Secret History of the Duke of Alançon and Q. Elizabeth. A True History (London: Printed for Will of the whisp, at the Sign of the Moon in the Ecliptick, 1691). All quotations from these editions.

[4] N. N. The Blatant Beast Muzzl’d, or, Reflexions on a late libel entituled, The Secret History of the Reigns of K. Charles II and K. James II (London, 1691), “To the Reader” (8).

[5] Walter Bagehot, The English Constitution, ed. Paul Smith (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001). 37.

From a dedicated and, I guess, decent enough scholar to an unabashed and unapologetic novelist, my journey has culminated in a novel employing my previous scholarship and deep interest in one of the most fascinating, yet still generally under-appreciated, periods of English history—the Restoration. The novel The King’s Favorite (published by an independent press in the summer of 2018) is a mystery thriller featuring fictional and factual characters—most notably Lady Castlemaine, Nell Gwynn, and Charles II. The genesis of the novel goes back almost twenty years, when I was mixing my scholarly work with my dormant love of theater, which recommenced in 1986 when I agreed to portray Ernest in Wilde’s memorable comedy. In addition, I wrote thirty-five plays from 1994 to 2011, one of them being “The King’s Favorite,” a play I didn’t intend to cast and present to an audience as I did the others. The following year, at the 2000 SEASECS conference in Savannah, I read a paper on the construction of the drama, which concentrated primarily on four women–two fictional and the other two being Barbara Villiers and Nell Gwynn. Returning home after the conference, I deposited the paper in the archives, assuming I would do nothing more with it.

From a dedicated and, I guess, decent enough scholar to an unabashed and unapologetic novelist, my journey has culminated in a novel employing my previous scholarship and deep interest in one of the most fascinating, yet still generally under-appreciated, periods of English history—the Restoration. The novel The King’s Favorite (published by an independent press in the summer of 2018) is a mystery thriller featuring fictional and factual characters—most notably Lady Castlemaine, Nell Gwynn, and Charles II. The genesis of the novel goes back almost twenty years, when I was mixing my scholarly work with my dormant love of theater, which recommenced in 1986 when I agreed to portray Ernest in Wilde’s memorable comedy. In addition, I wrote thirty-five plays from 1994 to 2011, one of them being “The King’s Favorite,” a play I didn’t intend to cast and present to an audience as I did the others. The following year, at the 2000 SEASECS conference in Savannah, I read a paper on the construction of the drama, which concentrated primarily on four women–two fictional and the other two being Barbara Villiers and Nell Gwynn. Returning home after the conference, I deposited the paper in the archives, assuming I would do nothing more with it.

In addition to publishing work on Wycherley, Dryden, Pepys, Cibber, Garrick, and Sheridan, my love of and experiences in the theater demanded that I write into the novel a number of scenes set at the Kings Theatre. Here I was forced to give Tom Killigrew the old heave-ho and replace him with a fictional character involved in the comings and goings of the plots. But actual actors and actresses are mentioned and/or discussed (some substantially) by the characters, as are some forty other historical persons—from Peter Lely and the Duke of York to Queen Catherine and Louise de Kérouaille.

In addition to publishing work on Wycherley, Dryden, Pepys, Cibber, Garrick, and Sheridan, my love of and experiences in the theater demanded that I write into the novel a number of scenes set at the Kings Theatre. Here I was forced to give Tom Killigrew the old heave-ho and replace him with a fictional character involved in the comings and goings of the plots. But actual actors and actresses are mentioned and/or discussed (some substantially) by the characters, as are some forty other historical persons—from Peter Lely and the Duke of York to Queen Catherine and Louise de Kérouaille.

Other secret histories, however, do not fit this pattern: they are not overly partisan and they aim to allow readers access to the affective lives of royal figures even while their narrative structures reinforce the implausibility of their claims. These are the secret histories of Queen Elizabeth–the first, not the second. In 1680 The Secret History of Q. Elizabeth and the E. of Essex was anonymously printed in London, while The Secret History of the Duke of Alancon and Q. Elizabeth was first published in 1691. [3] Both continued to be widely reprinted in cheap editions across the eighteenth century, and the accounts they offered were reimagined in chapbook romances, plays, and operatic songs.

Other secret histories, however, do not fit this pattern: they are not overly partisan and they aim to allow readers access to the affective lives of royal figures even while their narrative structures reinforce the implausibility of their claims. These are the secret histories of Queen Elizabeth–the first, not the second. In 1680 The Secret History of Q. Elizabeth and the E. of Essex was anonymously printed in London, while The Secret History of the Duke of Alancon and Q. Elizabeth was first published in 1691. [3] Both continued to be widely reprinted in cheap editions across the eighteenth century, and the accounts they offered were reimagined in chapbook romances, plays, and operatic songs. Both books call into question the celebrated history of Elizabeth’s reign and her status as an exemplar of Protestant queenship. The Secret History of Elizabeth casts the queen as exceptional but amorous, ruled by her love for Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, reinterpreting his rise, rebellion, and subsequent execution in 1601 as a consequence of the queen’s jealousy and manipulation by courtiers. In The Duke of Alançon, the marriage negotiations that took place between Elizabeth and the French prince in the late 1570s are reimagined to depict the queen as a power-hungry ruler whose love of independence leads her to reject all possible suitors and murder a made-up member of the royal family. Inexpensive and widely available, these stories perhaps invited middling readers to compare themselves favorably to Elizabeth.

Both books call into question the celebrated history of Elizabeth’s reign and her status as an exemplar of Protestant queenship. The Secret History of Elizabeth casts the queen as exceptional but amorous, ruled by her love for Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, reinterpreting his rise, rebellion, and subsequent execution in 1601 as a consequence of the queen’s jealousy and manipulation by courtiers. In The Duke of Alançon, the marriage negotiations that took place between Elizabeth and the French prince in the late 1570s are reimagined to depict the queen as a power-hungry ruler whose love of independence leads her to reject all possible suitors and murder a made-up member of the royal family. Inexpensive and widely available, these stories perhaps invited middling readers to compare themselves favorably to Elizabeth.