Slaves in the Hold of the Albanoz (1846) by Lt. Francis Meynell © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

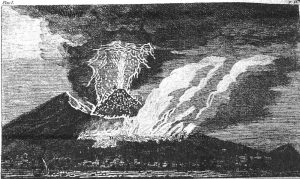

Shortly after midnight on March 18, 1973, the Zoe Colocotroni, an oil tanker commissioned by Mobil Oil Company, ran aground off the southwest coast of Puerto Rico near Bahía Sucia. Before seeking outside help, the ship’s captain, Anastacios Michalopaulos, frantically ordered the crew to jettison over 37,000 barrels of crude oil—approximately 1.5 million gallons—into the ocean. Dumping the oil lightened the ship enough to free it from the sand and allowed Michalopaulos successfully to deliver the payload, while absorbing only a partial loss (the Colocotroni had been transporting 187,670 barrels altogether). The surrounding environment experienced more than a partial loss and the resulting disaster is part of a long history of environmental degradation in the Caribbean; one that dates back to the “ecological maelstrom” unleashed on the region in the eighteenth century amid the heyday of sugar cultivation and the dawning of the Anthropocene [1]. Flora and fauna from the reef and nearby mangrove swamps suffered extensive damage as the oil slick quickly spread, eventually covering a four-mile stretch of coastal waters. Puerto Rico’s Environmental Quality Board established that in total the spill cost approximately $6 million (equivalent to roughly $35 million in 2019) in damage and clean-up efforts and resulted in the deaths of over 92 million marine organisms [2].

Oil from the Deepwater Horizon explosion washing up on Bon Secour National Wildlife Refuge (2010) by Jereme Phillips

Like many man-made environmental disasters, the Colocotroni spill is remembered today as a freak accident aggravated by human error; an exception rather than the rule of oceanic commerce. It would be more appropriate, however, to locate in this incident something emblematic about maritime trade in the Anthropocene; the proposed geological epoch in which human activity has emerged as a “geophysical force on a planetary scale” [3]. Indeed, that it was petroleum—the cornerstone resource of the industrialized world—washing over the beaches and forests of a Caribbean island, ground zero for European imperial expansion, alerts us to the intersecting legacies of colonialism, capitalism, and ecological destruction underpinning Michalopaulos’s actions. To label the Colocotroni spill as a mere externality, then, would be to ignore the ways in which the indiscriminate dumping of cargo into the sea has historically been employed in the service of modern political and economic regimes. Tempting as it may be to attribute the disaster in Bahía Sucia to a simple miscalculation made in a moment of panic, we ought instead to identify in Michalopaulos’s decision to jettison the ship’s crude oil stores a specific, historically situated strategy of Anthropocene colonialism [4].

One of the major contributions of social scientists and humanists working in waste studies has been their recognition that the things we throw away say as much about who we are as the things we preserve [5]. This insight invites us to study the flotsam and jetsam cast off ships like the Colocotroni not as unfortunate byproducts of maritime trade but as tools enabling capital accumulation and colonial expansion. Given how voluminous marine debris has become in the world’s oceans, a new approach that takes flotsam and jetsam more seriously as material actors is surely needed. Cargo dumped from seafaring vessels—both intentionally and unintentionally—has in fact become so common that it now amounts to a stratigraphically legible form of human activity. While industrial manufacturing, nuclear testing, and factory farming have become the de facto symbols of the Anthropocene, numerous geologists, paleontologists, and environmental historians have stressed the importance of commercial shipping (and ballast shipping in particular) in producing the stratigraphic signature of this human age [6]. In addition to the lifeforms jettisoned by ballast tanks, the plastic, metallic, and organic flotsam and jetsam routinely cast off cargo ships, cruise liners, and sailboats are now visible in the fossil record in and around busy ports and heavily trafficked shipping lanes throughout the world.

Jonah Cast into the Sea (17th Century) by Dominicus Custos

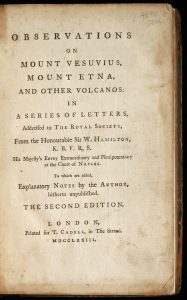

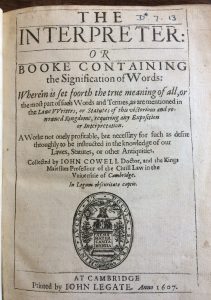

Flotsam, jetsam, and lagan have existed for as long as people have been sailing. Before the practice appeared in the stratigraphic record, accounts of sailors dumping cargo in order to save ships in distress or in danger of sinking appear in the written record dating back to the Book of Jonah. It is within the lexicon of colonialism, though, that these concepts take on their modern character. Heightened interest in these terms was due in large part to the massive expansion of commercial shipping between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, when the extraction and transportation of resources from colonial outposts back to Europe increased exponentially. As more and more ships began transporting commodities to and from Europe’s colonies, there was a corresponding increase in shipwrecks, attacks, and other accidents, filling the Caribbean with commodities, raw materials, and trash lost from these vessels and necessitating clearer parameters regarding how to define these objects and to whom they belonged. Unsurprisingly, then, the Oxford English Dictionary dates the first recorded use of “jetsam” to 1491, on the eve of American colonization, while “flotsam and jetsam” first appear alongside one another in The Interpreter (1607), John Cowell’s early law dictionary [7]. Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, flotsam and jetsam appeared frequently in legal treatises, dictionaries, and pamphlets, emerging as concepts of immense social consequence within contemporary debates on property, ownership, and appropriation that would support the advancement of colonialism.

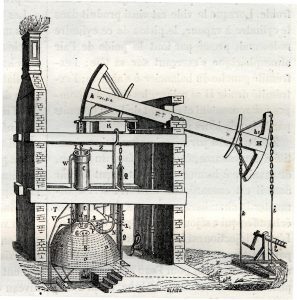

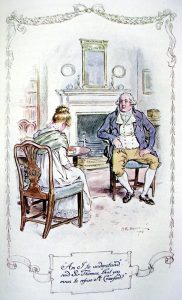

Implicitly included in these debates on property were the enslaved Africans whose bodies occupied a position as prime movers of the colonial economy. Throughout the nearly four centuries of the transatlantic slave trade, the millions of men, women, and children subjected to the horrors of the Middle Passage were as expendable as any other commodity. This became increasingly true at the turn of the eighteenth century when a “pricing revolution” in the marine insurance markets resulted in increasingly widespread use of insurance underwriters on commercial voyages [8]. Whereas flotsam and jetsam had long symbolized outright losses for stakeholders, lost cargo that had been properly insured could now be written off, leaving sailors more inclined to part with their commodities—human beings notwithstanding—if circumstances required.

Frontispiece of The Interpreter (1607) by John Cowell

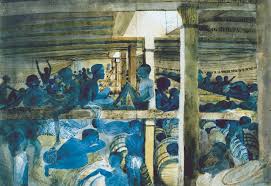

When it comes to the jettison of insured cargo, there is no more shocking case than the events that unfolded aboard the slave ship Zong some two hundred years prior to the Colocotroni’s spill in Bahía Sucia. The Zong, another cargo ship—this one transporting 442 enslaved Africans—was en route to Jamaica from Accra (in what is now Ghana) when it mistakenly overshot its destination, adding nearly two weeks to the voyage. Overcrowded and running low on drinking water, the crew convened and determined that “part of the slaves should be destroyed to save the rest” [9]. Beginning on the night of November 29, 1781, the ship’s captain, Luke Collingwood, ordered the crew to jettison a total of 132 men, women, and children over the course of two weeks, while an additional 10 jumped overboard in an act of courageous defiance. Having insured the slaves for £30 each, the crew claimed to have determined that the best option was to ensure that the majority of the slaves onboard made it to market by “destroy[ing]” all but whom their rations could support, and then filing insurance claims on those losses. However, dating back to the abolitionist Granville Sharp, critics of the Zong massacre have noted that the ship may in fact have had enough water to make it to port, leading to speculation that the crew simply jettisoned the sick and dying because their deaths on board would not be covered by the voyage’s insurance policy. The massacre, then, was carried out, according to Sharp, in an effort to “throw the loss upon the insurers, as in the case of Jetsam” [10]. A well-publicized court case followed, but at stake in the case was only the validity of the insurance claims made by the ship’s owners. The murdered were, as Christina Sharpe has noted, merely committed to the official historical record as lost property—as jetsam [11].

“The Slave Ship” (1840) by J. M. W. Turner

In her reading of “The Slave Ship,” J. M. W. Turner’s painting inspired by the Zong massacre, Sharpe notes that Turner’s decision to leave the ship unnamed “refuses to collapse a singularity into a ship named the Zong; that is, Turner’s unnamed ship stands in for the entire enterprise” [12]. The generic quality of the painting Sharpe identifies is important in the context of this piece, for while the Zong is often invoked as a disturbing outlier, the jettison of enslaved passengers was standard operating procedure in the transatlantic slave trade. Like the Colocotroni, the massacre that took place aboard the Zong was no mere accident, nor was it simply the act of a psychopathic crew. Rather, both events present us with instances of the same deliberate strategy of the colonial economy; in each case, a manufactured loss that ultimately engendered a profitable return.

Separated by two centuries, the incidents that occurred aboard the Colocotroni and the Zong might appear unrelated if not for their shared production of oceanic waste in the form of the petroleum and human cargo jettisoned from their respective holds. It is possible to imagine the sea floor along the heavily trafficked shipping routes of the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea littered with a combination of human and nonhuman remains jettisoned from the countless slave brigs, container ships, and oil tankers that have passed through those waters. That this emblematic form of human activity in the Anthropocene was also employed as a deliberate strategy of the transatlantic slave trade calls to mind the notion of a “Plantationocene” popularized by Anna Tsing and Donna Haraway; a term used to highlight the radical transformation of land into “extractive and enclosed” plantations through the use of “slave labor and other forms of exploited, alienated, and usually spatially transported labor” [13]. The pairing, moreover, affirms Kathryn Yusoff’s contention that the onset of the Anthropocene cannot be distinguished from the institution of slavery. Yusoff focuses on the “grammars” of extraction that enable industries like slavery and surface mining–and colonialism and geology more generally–but these entwined logics also remained in place when it came to disposing of the commodities produced by these systems [14]. The intersecting histories of environmental degradation and racial violence that have come into focus in the work of environmental justice scholars and activists come together yet again when we consider how, why, and under what conditions flotsam and jetsam are produced; when we interrogate what or who is expendable within the extractive logics of the Anthropocene.

Notes

[1] Philip D. Morgan, “The Caribbean Islands in Atlantic Context, circa 1500-1800.” The Global Eighteenth Century. Ed. Felicity Nussbaum. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. 57.

[2] Commonwealth of Puerto Rico vs. The SS Zoe Colocotroni, 456 F. 1327 (District of Puerto Rico 1978).

[3] Timothy Morton, Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016. 20.

[4] My use of “strategy” here is borrowed from Raj Patel and Jason W. Moore, A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017.

[5] See Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and its Outcasts. Cambridge: Polity, 2004; Vittoria di Palma, Wasteland: A History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015; Sophie Gee, Making Waste: Leftovers in the Eighteenth-Century Imagination. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010; William Viney, Waste: A Philosophy of Things. London: Bloomsbury, 2004; Traci Brynne Voyles, Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

[6] For a discussion of the relationship between commercial shipping and the onset of the Anthropocene, see J. R. McNeill and Peter Engelke, The Great Acceleration: An Environmental History of the Anthropocene since 1945. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016; N. Neeman, J. A. Servis, and E. Naro-Maciel, “Conservation Issues: Oceanic Systems.” Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene. Vol. 2. Ed. Dominick A. DellaSala and Michael I. Goldstein. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2017. 193-200; James Syvitski, Jan Zalasiewicz, and Colin P. Summerhayes, “Changes to Holocene/Anthropocene Patterns of Sedimentation from Terrestrial to Marine.” The Anthropocene as a Geological Time Unit: A Guide to the Scientific Evidence and Current Debate. Ed. Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N. Waters, Mark Williams, and Colin Summerhayes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019. 107.

[7] “flotsam, n.” OED Online. March 2019. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com.ezproxy.rice.edu/view/Entry/71946?redirectedFrom=flotsam (accessed March 28, 2019); “jetsam, n.” OED Online. March 2019. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com.ezproxy.rice.edu/view/Entry/101177?redirectedFrom=jetsam (accessed March 28, 2019).

[8] See A. B. Leonard, “The Pricing Revolution in Marine Insurance,” working paper presented to the Economic History Association, Sept. 2012, http://eh.net.eha.system/files/Leonard.pdf (accessed 3 June 2019).

[9] Testimony of James Kelsall, National Maritime Museum (NMM) REC/19 (formerly MS 66/069); quoted in Andrew Lewis, “Martin Dockray and the Zong: a Tribute in the Form of a Chronology.” Journal of Legal History 28.3 (2007): 364.

[10] Granville Sharp, Memoirs of Granville Sharp. Ed. Prince Hoare. London: Colburn, 1820. Appendix viii.

[11] Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Donna Haraway, “Anthropocene, Capitolocene, Plantationocene, Cthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6 (2015): 162.

[14] Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes Or None. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019.