This is a collaborative piece that has emerged out of interviews between Peter Brathwaite and Kerry Sinanan in response to Brathwaite’s Rediscovering Black Portraiture project, 2020. [1]

. . . (And whose boy am I, and what is

my name?). Black erasing blackness,

body and backdrop: you are not permitted to enter

the question light asks of his skin as if it were

a field, a mind, a word inclined to be

entered.

–From “Vanitas with Negro Boy”, Rickey Laurentiis[2]

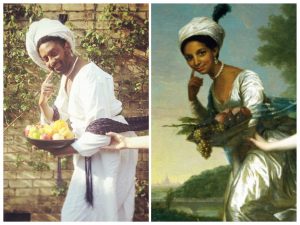

Black Servant, England. Unknown artist (1760-1770).

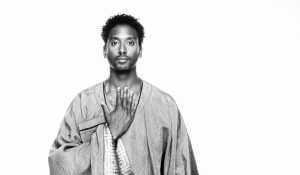

In 10 April 2020, in response to the Getty Museum Challenge to recreate famous works of art on social media during COVID lockdown, Peter Brathwaite, the internationally renowned opera singer, offered Twitter what he thought would be a sole contribution to the project, namely a reworking of an anonymous and not very well-known portrait, Black Servant, ca. 1760-1770.[3] On 29 May, Brathwaite reached 50 reworkings and is continuing now with the work in order, as he says, to “amplify marginalized voices” from the past. In this first painting a smiling Black boy holds aloft a large glass in one hand, and a silver charger in the other, with a small spaniel looking up at him adoringly. This is a classic eighteenth-century scene: enslavement is veiled with civility, materially by the boy’s white shirt and genteel clothes, and ideologically by the presentation of this as a somehow “natural”, unquestioned scene of servitude. The coupling of the Black boy with a pet is common for the period, as Catherine Molineaux writes: “acquiring pets, black slaves and fashionable animals became a form of social currency; they became objects consumed and displayed in a semiotic system of status”.[4] In this system of displayed “objects” the roemer glass, prized for its greenish tint, is notably large and copiously filled, and, alongside the enslaved boy and silverware, works to construct a politeness that is both British and white. As Sinanan has recently argued, displaying glass objects alongside enslaved people is central to the construction of politeness. Many eighteenth-century paintings juxtapose blackness with more modern, transparent, lead glass to do this work in an even more explicit way: “blackness, alongside . . . glass that is prized for its ‘purity,’ intensifies the rhetorical construction of whiteness”.[5] In this image, though, whiteness is constructed through a painterly focus on colour: the boy’s blackness becomes fetishized beside the tints of the wine, the greenish glass and the silver. The boy’s “colour”, rather than his personhood, makes him suitable as an artistic subject. As the eighteenth-century aesthetic theorist, Uvedale Price writes in his Dialogue on the Distinct Characters of the Picturesque and the Beautiful (1801), “blackness . . . has a richness, which, in the painter’s eye, may compensate its comparative monotony, and may, therefore . . . be called beautiful”. Price continues to discuss Joshua Reynold’s painting of Samuel Johnson’s servant, Francis Barber, to emphasize the focus on blackness as being on “tint”, “tone” and “colouring”.[6] While we see a Black servant smiling, he is the subject of a portrait composed by white ideals of the picturesque that racialized skin tone to present the boy for a white gaze.

In Brathwaite’s re-presentation, though, we do not see this portrait alone: alongside it is Brathwaite’s reworking that immediately challenges the eighteenth-century dynamics at work. Brathwaite’s emphasis of the boy’s smile, a more open and slightly freer expression, highlights what is already apparent: this Black boy is a person, not merely a subject of artistic interest, with a real history and life, but one that is erased and not accessible beyond the frame of the painting. The re-portrait prompts questions we may not as readily ask of an artefact located at an historical distance. A free Black man, now, joining his own history and personhood to the boy’s through this reworking, disrupts the naturalization of the eighteenth-century composition to reveal the picturesque scene, using colour, tint, and servitude to forge politeness, as in fact comprising oppression and barbarity. That such a corrective is needed is evidenced by the description of the painting in the Philip Mould Historical Portraits Image Gallery which currently describes the boy as being “a favoured companion” with an “intimate position in his master or more probably mistress’s household . . .trusted and loved by their lapdog”.[7] Such a reading accepts as natural the racialized hierarchies of the boy’s position, and dismisses the realities of Black servitude and enslavement in Britain and its colonies in the mid-eighteenth century to prioritize white affection. As Peter Erickson asserts, “Inclusion of the black servant does not represent benign inclusiveness but is rather keyed to incorporation into a visual regime structured in white dominance”.[8] While in the original portrait the Black boy already disrupts the desired display of objects for consumption with his inevitable personhood, this is much more forcefully felt in the re-portrait. Brathwaite’s free, Black, present personhood, combined with his satire of the spaniel with a stuffed sheep, emphasizes the violence of fetishization and objectification required by eighteenth-century white politeness to construct itself. 250 years after the original portrait, Brathwaite’s re-portrait, with his free smile, offers a “subversive” judgement on the consuming vulgarity of a declined slave-owning culture.

Such a reading – more attentive to the sacrifices required of Black people to make whiteness – has become impossible to avoid in the present context of COVID in which we see significantly higher rates of death and infection among Black people both in the UK and in the US. Since March it has become clear that COVID is wreaking disaster on Black people precisely because systemic racism has left them most vulnerable to its ravages.[9] And within this context, Brathwaite’s portraits give life to figures from the long eighteenth century whose histories and identities were seized by the racist forces that defined the period.

The new venue for their viewing is Twitter, which allows Brathwaite to present both the original painting and his own reworking simultaneously in a Tweet thus visually embedding the latter’s disruptive reworking in the former. Brathwaite names his acts of re-creation as “re-imaginings, disruptions and a re-empowering” and describes his research to find portraits as an “archaeology” a “digging things up”: we are presented with what has been occluded by white canons of art and asked to look at these images in a radical new way. The term “re-portrait” describes the complete image created by Brathwaite that captures both the original painting or photograph, and his own reworking simultaneously, with the hyphen registering both the splice and join of the new image allowed for by social media.[10] The reaction that Brathwaite received to this first re-portrait spurred him on to do more as he realized the “open-ended, wide platform” offered for this vital work of curation and re-creation. The urgency of such a project is even more clear during the rise of BLM 2020 which, in response to the murders of Breonna Taylor, Nina Pop, Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and, during the period of protest itself, of Tony McDade, David McAtee, and Rayshard Brooks, has become a global movement for Black liberation. At the time of writing, the protests are in their sixth week and continue to take place all over the world: tragically, so do police brutality and hate crimes against Black people. In this context, Brathwaite’s re-imaginings inevitably become another crucial way to assert, not just the importance of Black life, but the vitality, creative energy, variety, and resistant thriving of it in the face of overwhelming odds.

In Aberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of Color Critique, Roderick Ferguson emphasizes the “social heterogeneity that characterizes African American culture” due to its inherent queerness which, he argues, is embodied in the “estrangements” of the Black drag-queen prostitute. This figure, Ferguson argues, “allegorizes and symbolizes” how

African American culture indexes a social heterogeneity that oversteps the boundaries of gender propriety and sexual normativity. That social heterogeneity also indexes formations that are seemingly outside the spatial and temporal bounds of African American culture.[11]

Brathwaite’s work produces beyondness and extraneousness that, interfusing with Brathwaite’s own Bajan roots, presents us with a global sense of Black heterogeneity across centuries, disrupting the raced and gendered norms that encoded Black enslavement and servitude. Encompassing artworks from the 15th century to the present day, Brathwaite has curated portraits of gondoliers, ambassadors, menagerie keepers, flower sellers, street artists, chimney sweeps, soldiers, actors, noble women and more. These figures cross gender, class, and national boundaries, creating a powerful representation of global, heterogeneous Blackness that exceeds the static, foundational image of the enchained Black person as chattel, while also disrupting the libidinal economies of slave culture. As James Edward Ford asserts, “Whiteness takes shape partly through financial economy and partly through libidinal economy”.[12] Brathwaite’s mode of re-portrait on the Twitter platform wrests the Black subject from white libidinal framing to re-present it in Black repossession, creativity and ownership: his re-portraits are forged by a Black gaze. As an opera singer, Brathwaite also regards each re-portrait as a performance complete with set, costume, and his embodiment of the person whom he is re-presenting. In many of the re-portraits Brathwaite uses personal belongings and artefacts of his Bajan culture and such heterogenous, Caribbean Blackness presents a powerful riposte to slavery’s legacy of racist violence.

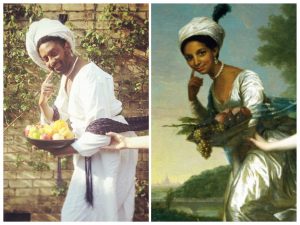

Dido Elizabeth Belle and Elizabeth Murray, by David Martin (c.1778)

We can see such heterogeneity in one of the most striking 18th-century images in his curation, that of Portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle (1761-1804) and her cousin Elizabeth Murray (1760-1825), by David Martin (ca. 1778).[13] In his re-portrait, the original double portrait is cropped, taking Elizabeth Murray out and leaving only Dido. In this powerful move, Brathwaite reverses the dynamics of racist exclusion to center Dido as the main figure alongside his reinterpretation. While most of the re-portraits Brathwaite has made are of men and boys, here, we clearly see the relevance of Ferguson’s idea of Black culture as figured by the heterogeneity of drag. Brathwaite did not explicitly have this idea in mind when he produced his Dido, but acknowledges the potential for radical heterogeneity in his “cross-dressing” image. This particular representation of Blackness, already transgressive in Martin’s painting, is accentuated by Brathwaite “to subvert” as the re-portrait crosses gender and raced norms. Arguably, Brathwaite’s beard is not the most disruptive aspect of the re-portrait: rather it is his smile and, as he asserts, the “cheeky expression” he deliberately creates to accentuate his Dido’s freedom and independence. Brathwaite consciously infuses his performance and posing for the reworkings with new, subtle interpretations of the figures’ looks, postures and positions that force questions about the dynamics of oppression and emancipation at work. Here, Brathwaite reads the original painting of Elizabeth Murray’s hand on Dido as perhaps “a push” away, out of the space and thus in the re-portrait the hand is more of a grip, either of welcome or of possession, registering the libidinal economies of white/Black relations.

As Gretchen H. Gerzina discusses, how to read the women’s poses in the original double portrait remains contested and she argues that “the two cousins exhibit a closeness and ease”, “like sisters”, that they are comfortable to express to the painter.[14] Yet, such sisterliness cannot transcend the raced dynamics within the portrait as we read the contrast of Dido’s white silk dress against her skin and the luminous whiteness of Elizabeth’s body. Elizabeth is to the fore, albeit the running Dido somewhat decenters her. The bond the women had cannot escape these dynamics, imbricated, as it was, materially in the fact that Dido’s own mother was an enslaved woman and in the fact of Dido’s blackness.[15] Reading intimacies within such economies is fraught. In his reworking, Brathwaite deliberately presents Dido as “delighting” in her movement away, and as more mischievously rejecting the claim of whiteness upon her as she runs into the light, refusing her role as “bearer” even to a loving cousin. While these disruptions are apparent in the original painting, the drag dynamic of Brathwaite’s re-portrait registers the productive heterogeneity of Dido and accentuates the emancipatory potential to make Dido both “more comfortable and powerful”, and, crucially, uncoupled from the white femininity of her cousin.

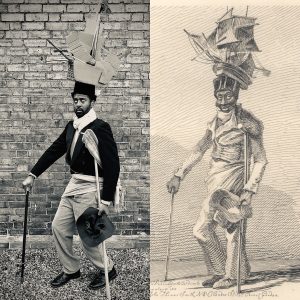

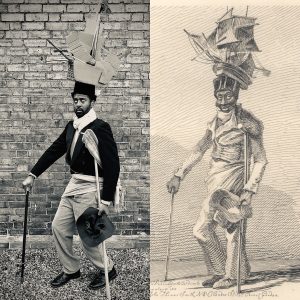

Joseph Johnson, by John Thomas Smith (1815).

Brathwaite’s re-portraits also present Black heterogeneity in terms of class. On the point of completing fifty re-portraits, Brathwaite launched an online vote for the public’s favourite and an image from the long eighteenth century won, an etching of Joseph Johnson by John Thomas Smith (1815). Johnson was a former Merchant Navy seaman who had been reduced to homelessness in London after the Napoleonic Wars. He devised an act of street art in which he built and wore a large wooden model of the HMS Nelson to busk for money. On a very basic level, it is remarkable that Brathwaite’s work has brought this image of a free but poor Black man in nineteenth-century Britain to public attention, especially in the current moment. The original print first appeared in a set, originally entitled, Etchings of Remarkable Beggars, Itinerant Traders and Other Persons of Notoriety In London and Its Environs (1815). As Eddie Chambers writes:

Within a year or so, the prints appeared in book form, the publication having been given the equally extravagant title Vagabondiana or, Anecdotes of Mendicant Wanderers through the Streets of London; with Portraits of the Most Remarkable, Drawn From the Life by John Thomas Smith (Keeper of the Prints in the British Museum) produced etchings that were amongst the earliest attempts to depict the poor of London in ways that sought to avoid caricature, and relied to some extent on the artist’s quest to capture the personalities of his subjects as well as the hardships they reflected.[16]

Chambers’ detailed account of Johnson emphasizes how he was able to create a novel and effective act of street art to survive. The subversive potential of Johnson’s act was considerable: his choice of the Nelson immediately located him in a British narrative of heroism, the Battle of Trafalgar, familiar to all, to counteract his precarious status. Johnson’s act affirms that he, too, is a Briton. Chambers asserts that this print is also “one of the first documented examples of a Black-British artist (in this case a sculptor) in London”.[17] The original print certainly registers the carnivalesque potential of Johnson, further accentuated by Brathwaite’s re-portrait which displays the multi-faceted skill it would have taken accomplish such an act from sculpting to busking. As we think of Brathwaite preparing for his performance, we simultaneously think of Johnson preparing for his and become more aware of the artistry involved. Brathwaite’s crafting of his ship from cardboard highlights the self-made aspect of Johnson’s much more accomplished sculpture, and Brathwaite’s outfit and selected props all intensify the deliberate performance elements of Johnson, showing him to be in charge of his own art as protest. As Brathwaite notes on his online gallery, the sight of a ship on a Black man’s head would also have likely reminded his audience and passers-by of the slave ship: Johnson is physically “below deck” having placed the ship on his own head but now as a free man who has reinterpreted the ship as a sign, not just of white liberty, but of Black emancipation. While the transatlantic slave trade had been abolished in 1807, emancipation was still a long way off. Johnson’s performance was also, then, an anti-slavery disruption of the libidinal economies of consuming sugar and other goods from the Caribbean, redirecting pleasure into subversive laughter. The sense of the Black person as “carrying” a culture dependent on slavery is captured by Brathwaite’s re-portrait in which his more serious expression as he looks up at this ship, registers a sense of judgement and weariness. That the public on Twitter selected Johnson as their favourite re-portrait speaks to the current rise in an awareness of transatlantic slavery’s role in the present and of how this re-portrait has reframed Johnson as an abolitionist precursor to Black Lives Matter protest in the eighteenth century.

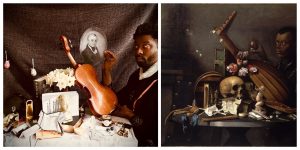

Still Life with Moor and Parrot by Jan Davidz. de Heem (1641).

The heterogeneity of global Blackness is visible in the props Brathwaite uses to replace objects in the original paintings. Thus, in Jan Davidsz De Heem, Still life with Moor and Parrot (1641), Brathwaite replaces the mirror, a sign of vanity, with an African print, and the luxurious lobster with Caribbean saltfish and pepper sauce. The props of white power, already critiqued in the original vanitas genre, are now replaced by productive Black lives and cultures that have survived enslavement. These supplantings are also critiques, mocking the object-fixation that drove consumption in the long eighteenth century. That this consumption depended on the subjugation of colonized others is made clear by the Black boy to the right, peeking in on this display of artefacts, to become another “object” in the display. However, in Brathwaite’s re-portrait, the figure’s gaze falls mockingly on a copy of Richard Ligon’s A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes (1657), instead of on the monkey he is visually twinned with in the original. As Molineaux argues, the “association of blacks and monkeys as common products of the African continent” was prevalent in the period that regarded both as exotic accoutrements of fashionable life.[18] Ligon could simply not have imagined the Black lives that would emerge from the practices of plantation slavery that he witnessed being tried and tested in mid 17th-century Barbados: in Brathwaite’s display Ligon’s History, in which enslaved people are listed as “stock” along with “Horses, Cattle, Camels” becomes a piece of old bric à brac, debunked and looked on with appropriate mockery.[19]

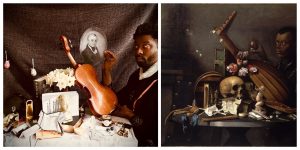

Vanitas with Negro Boy by David Bailly (1650).

The challenge to white patriarchal slave culture is challenged in many re-portraits. In his reworking of David Bailly’s Vanitas with Negro Boy (ca.1650), Brathwaite replaces the miniature portrait of the white patron held by the Black boy, with “a picture of my ancestor Miles Brathwaite and the will of a Planter great-grandfather”. At the other end of slavery’s long history, the manumission papers of Brathwaite’s great, great, great, great-grandmother, Peggy, are held by him in his re-portrait of H.L. Stephens’ Man Reading Headline: Presidential Proclamation, Slavery (1863). Working with a researcher, and in the Barbados archives, Brathwaite was able to recover these vital documents of his own family’s emancipation on his mother’s side. As Hortense Spillers tells us, the scene of slavery’s capture of African people, “marked a theft of the body—a willful and violent (and unimaginable from this distance), severing of the captive body from its motive will, its active desire”. This captive body, separated from a more liberated pre-captive flesh, is for Spillers “as a category of otherness . . . embodies sheer physical powerlessness that slides into a more general ‘powerlessness,’ resonating through various centers of human and social meaning”.[20] Brathwaite’s re-portraits seize Black people from the art of the long 18th-century in which they have been objectified as bodies. In Brathwaite’s re-portrait Peggy’s papers, held in the hands of her descendant smiling with glee, symbolically moves Peggy back into the flesh and blood of her free grandson. He holds her physically in his radical act of curation. Brathwaite’s Caribbean and Black British artefacts, along with his body that is able to perform and recreate these many moments, are signs of a global Black resistance movement for emancipation which, while still not fulfilled, remains a creative site of persistence.

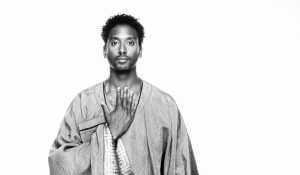

Brathwaite’s grandmother’s Bajan quilt hangs in many of the re-portraits as perhaps the most visually striking creative artefact, representing a new Caribbean culture of matriarchal materiality that replaces the materiality of patriarchal white power in the originals. This representation of Bajan folk art is vital for Brathwaite, not just as a riposte to the past, but also as a critique of current cultures of consumption in present-day tourism. Barbados remains in the British imagination as “Little England”, and British tourism a form of neo-colonial possession. In this economy of tourism in which Caribbean culture is commodified, as Brathwaite notes, older, Bajan “folk songs are now a dying culture”. Brathwaite places a book of Bajan folk songs in several re-portraits as he feels “an urgency to preserve them”.

The Paston Treasure, by unknown painter (1665).

In the painting, The Paston Treasure (ca. 1663) commissioned either by Sir William or his son Robert Paston, the plush red velvet hanging backdrop to the dizzying display of luxurious objects is replaced by his grandmother’s quilt, alongside a large swathe of fabric printed with repeating Union Jack flags. The drapings fuse Caribbean and Black Britishness, which claims the Union Jack, to represent the people who came to post-war Britain at the government’s invitation, to help rebuild the country. Brathwaite’s mother came to England from Barbados in the wake of the Windrush generation as a nurse and so both drapings can be read as matriarchal reclamations of the middle passage: the voyage of Caribbean people undertaken in the push for a better life, a self-determined step along the path to emancipation. Such a statement at a time when the British government continues its illegal deporting of Windrush generation British citizens to the Caribbean is even more vital. The quilt and the Union Jack, both repositioned and displayed in Brathwaite’s re-portrait, offer a powerful corrective to the histories of Black people in Britain as projected by colonial power.

In his reworking of The Paston Treasure, Brathwaite’s smiling figure replaces the Black boy as he looks up, once more, at a toy, stuffed-monkey. In the original, the racist twinning of the monkey on the boy’s shoulder again signifies the semiotic association in the long eighteenth century of monkeys with Black people, both reduced to consumable, exotic objects in this world of material wealth. Brathwaite’s figure, clothed in Côte d’Ivoire prints, has been reclaimed by African culture and sits among a range of Black cultural products that are not for white consumption. Brathwaite feels that such “standing in” for the original Black people in the paintings is a powerful act of curation which brings them back into Black ownership and into our present line of vision. That such a correction is vital is evidenced by the fact that a collaborative project on the painting in 2018 between Yale Center for British Art and Norwich Castle focuses on the painting as an object and on the history of the Paston family. In the specially commissioned short film about it, A Painting Like No Other, narrated by Stephen Fry, he describes the glittering objects and the painterly techniques that created them. The dimmed colours around the boy are noted: the “dazzling yellows have now faded to muted brown and the vibrant reds, are now grey”, Fry tells us. In contrast, Brathwaite’s re-presencing of the boy makes him the most notable aspect of the re-portrait which, while it imbues the original person with respect and visibility, also offers an important perspective on both a past and present fascination with material culture and its shiny things that can often obscure Black people, their lives, and their labour.[21] We see Brathwaite himself as an descendant of the boy, free and able to re-make The Paston Treasure with his perspective and creativity. Brathwaite displaces the objects in the vanitas, signs of dissolution and corrupt indulgence, with his and his family’s belongings, as the re-portrait title lists: “Reworked with – Afro hair products, Côte d’Ivoire prints, granny’s patchwork, Jessye Norman, Leontyne Price and family luggage from their arrival in the UK”. This is the new bric-à-brac, a living, creative culture of exchange, created by those who have come after the boy in the painting.

In his Nobel Prize for literature speech, ‘The Antilles: Fragments of Epic Memory’, Derek Walcott describes Antillean culture as comprised of “shards” and “pieces”:

Break a vase, and the love that reassembles the fragments is stronger than that love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole. The glue that fits the pieces is the sealing of its original shape. It is such a love that reassembles our African and Asiatic fragments, the cracked heirlooms whose restoration shows its white scars. This gathering of broken pieces is the care and pain of the Antilles, and if the pieces are disparate, ill-fitting, they contain more pain than their original sculpture, those icons and sacred vessels taken for granted in their ancestral places. Antillean art is this restoration of our shattered histories, our shards of vocabulary, our archipelago becoming a synonym for pieces broken off from the original continent.[22]

Brathwaite’s Black re-portraiture, like his grandmother’s colourful quilt, is composed of such lovingly gathered pieces, “restored” to presence in his new images. The word “curation” has its etymological roots in the word “cura”, meaning “to take care of”, and Brathwaite has taken great care to rediscover these paintings and images and refocus on the forgotten Black people within them. The “white scars” are visible in the spliced frames that both join and separate the pieces of the new work of art, like a quilt. His grandmother’s quilt, too, comprises gathered and kept “shards” of fabric, crafting the worn textiles into something vibrant to be passed on in an act of matrilinear continuity to heal the fragmentation of Antillean history that was underpinned by the separation of mothers from their children. In her essay “Odes to the Mountains of Jamaica”, Jacqueline Bishop writes about her Jamaican great grandmother and her last visit to her “maternal ancestral home”, Nonsuch, Portland. During her visit, Bishop ponders the quilts her great grandmother has made that she will inherit:

Spectacular quilts. Bold in colour, composition and design. . . I loved the piecing of things together, of trying to make something whole out of pieces, of something old taking on new life, of one thing becoming another; of making so much beauty out of the scraps of life.[23]

Like the quilts of Caribbean women, Brathwaite’s re-portraits gather and relocate eighteenth-century Black people into a new, Antillean art, rescuing them, reclaiming them from the possession of white culture back into the presence of Black inheritance.

Peter Brathwaite is a British opera singer. After his degree at Newcastle University he trained at the Royal College of Music, London and Flanders Opera Studio, Belgium. Recent and future engagements include performances with the Royal Opera House, English National Opera, Glyndebourne, La Monnaie, Nederlandse Reisopera, Opéra de Lyon and Opera North. He has written for The Guardian and The Independent. Documentary work includes BBC Radio 4’s Black Music in Europe 2, presented by Clarke Peters. He currently writes and presents features for BBC Radio 3’s Essential Classics. Peter is a Churchill Fellow, Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, and a Trustee of the Gate Theatre, London.

Peter Brathwaite is a British opera singer. After his degree at Newcastle University he trained at the Royal College of Music, London and Flanders Opera Studio, Belgium. Recent and future engagements include performances with the Royal Opera House, English National Opera, Glyndebourne, La Monnaie, Nederlandse Reisopera, Opéra de Lyon and Opera North. He has written for The Guardian and The Independent. Documentary work includes BBC Radio 4’s Black Music in Europe 2, presented by Clarke Peters. He currently writes and presents features for BBC Radio 3’s Essential Classics. Peter is a Churchill Fellow, Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, and a Trustee of the Gate Theatre, London.

Notes

[1] http://peterbrathwaitebaritone.com/rediscoveringblackportraiture Go to this website to see the re-portraits.

Direct quotations from Peter Brathwaite, taken from interviews conducted in May and June 2020 are in quotation marks.

[2] Rickey Laurentiis, Boy with Thorn (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015).

[3] Philip Mould names the painting as: A Servant ca. 1770. http://historicalportraits.com/Gallery.asp?Page=Item&ItemID=618&Desc=Black-servant,-Colonial-School-%7C-School–Colonial

[4] Catherine Molineaux, ‘Hogarth’s Fashionable Slaves: Moral Corruption in Eighteenth-Century London’. English Literary History, Volume 72, Number 2, Summer 2005, pp.495-520. 498.

[5] Kerry Sinanan, ‘Slavery and Glass: Tropes of Race and Reflection’. In In Sparkling Company: Reflections on Glass in the Eighteenth-Century World, ed. Christopher Maxwell (Corning: Corning Museum of Glass, 2020), 10.

[6] Uvedale Price, A Dialogue on the Distinct Characters of the Picturesque and the Beautiful, in Answer to the Objections of Mr Knight. Prefaced by an Introductory Essay on Beauty; with Remarks on the Ideas of Sir Joshua Reynolds and Mr Burke Upon the Subject (London: J. Robson, 1801), 53. See Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of a Man, probably Francis Barber, ca. 1770.

[7] Philip Mould, ‘Historical Portraits Image Gallery’, ‘A Servant c.1770’ http://www.historicalportraits.com/Gallery.asp?Page=Item&ItemID=618&Desc=A-Servant-%7C-Colonial-School Accessed on 22 June, 2020.

[8] Peter Erickson, ‘Invisibility Speaks: Servants and Portraits in Early Modern Visual Culture’. Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies, Spring-Summer, 2009, Vol. 9, No, 1, pp. 23-61. 34.

[9] See Orlando Patterson’s definition of slavery as ‘social death’ , now part of Afropessimism. See Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1982). And, Frank Wilderson, Red, White, and Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2010). And, Joy James, “Black Suffering in Search of the ‘Beloved Community’: Political Imprisonment and Self-Defence.” Trans-scripts: An Intersdisciplinary Online Journal in the Humanities and Social Sciences at UC Irvine 1 (2011).

[10] Brathwaite’s re-portraits can be viewed as part of a larger Caribbean culture of writing back, often undertaken by those in exile. Writers and poets including Louise Bennet, Jean Rhys, Derek Walcott, Kamau Brathwaite, George Lamming and Sam Selvon participate in this intertextual, corrective approach to Western literature. Alison Donnell describes this as ‘a counter-discursive (writing back) approach’. See, Alison Donnell and Sarah Lawson Welsh eds., The Routledge Reader in Caribbean Literature (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), 116.

[11] Roderick Ferguson, Aberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of Color Critique (London and Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 2-3. Ferguson mobilizes the figure of the Black drag queen prostitute to point out the ways in which she challenges the fixed categories of “identity” and difference, produced by sociology, that work to conceal intersectionality. His queer of colour critique offers ways to disrupt categories of racialized and sexualized difference to enable a more heterogeneous mode of critique that avoids curtailing disruptive, emancipatory cultural possibilities.

[12] James Edward Ford, Thinking through Crisis: Depression-Era Black Literature, Theory, and Politics (Fordham University Press, 2019), 183. Understanding the libidinal as interwoven with the material economies of slavery is fundamental to Afropessimism. As Frank B. Wilderson notes: “Jared Sexton describes libidinal economy as ‘the economy, or distribution and arrangement, of desire and identification (their condensation and displacement), and the complex relationship between sexuality and the unconscious.’ Needless to say, libidinal economy functions variously across scales and is as ‘objective’ as political economy. Importantly, it is linked not only to forms of attraction, affection and alliance, but also to aggression, destruction, and the violence of lethal consumption. Sexton emphasizes that it is ‘the whole structure of psychic and emotional life,’ something more than, but inclusive of or traversed by, what Gramsci and other Marxists call a ‘structure of feeling’; it is ‘a dispensation of energies, concerns, points of attention, anxieties, pleasures, appetites, revulsions, and phobias capable of both great mobility and tenacious fixation.’” In Red, White and Black. Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 7.

[13] As Gretchen H. Gerzina tells us, the attribution of the original double portrait has been contested. “Although long attributed to Johann Zoffany, there are now a number of reasons to suspect that the double portrait was painted by someone else. . . Most recent attributions settle upon David Martin, a fellow Sot who had painted the magnificent portrait of Lord Mansfield in his robes and was a protégé of the famous painter Allan Ramsay.” 171. Gerzina seems persuaded by the idea that both painters ‘had a hand in the painting’”. ‘The Georgian Life and Modern Afterlife of Dido Elizabeth Belle’. In Britain’s Black Past ed. Gretchen H. Gerzina (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2020), 172. The painting is now at Scone Palace, Perth, Scotland.

[14] Gerzina, 172.

[15] Gerzina’s work on Dido Belle is also based on the archival research undertaken by Sarah Murden and Joanne Major in their Blopost, All Things Georgian. See, “Dido Elizabeth Belle”, Joanne Major, June 26 2018. https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2018/06/26/revealing-new-information-about-dido-elizabeth-belles-siblings/?fbclid=IwAR3fcUm6bi2D_FIVaT2Ts1KIxXWr0C2yvIT3AXVUW1-K3j623Lv4VbJAcy4

See, “Dido Elizabeth Belle, her Portrait”, Sarah Murden, September 13, 2018. https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2018/09/13/dido-elizabeth-belle-her-portrait/

And, see Gerzina’s historical account of Maria Belle and Sir John Lindsay, Dido’s parents, pp. 163-166. “Speculation has always suggested that Maria was taken as a prize from a Spanish ship and was an enslaved person when she was ‘acquired’ by Lindsay, who freed her at some point before 1772”, 164.

[16] Eddie Chambers, Black Artists in British Art. A History since the 1950s (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), xii.

[17] Chambers, xv.

[18] Molineaux, 511.

[19] Richard Ligon, A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes (London: Humphrey Moseley, 1657), 108.

[20] Hortense J. Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Diacritics 17, No. 2, 1987: 65-81. 67.

[21] The urgent need to address this history of the erasure of slavery and Black people from British cultural history has recently been described by Sally-Anne Huxtable in Addressing the Histories of Slavery and Colonialism at the National Trust (National Trust, 2020). https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/addressing-the-histories-of-slavery-and-colonialism-at-the-national-trust Accessed on 24 June, 2020.

[22] Derek Walcott, ‘The Antilles: Fragments of Epic Memory’, Nobel Lecture, December 7, 1992. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1992/walcott/lecture/ Accessed on 24 June, 2020.

[23] Jacqueline Bishop, “Odes to the Mountains of Jamaica”, Woman Speak. A Journal of Writing and Art by Caribbean Women (WomenSpeak Books, 2016). Vol. 8, 2016. Ed. Lynn Sweeting, 98.

Peter Brathwaite is a British opera singer. After his degree at Newcastle University he trained at the Royal College of Music, London and Flanders Opera Studio, Belgium. Recent and future engagements include performances with the Royal Opera House, English National Opera, Glyndebourne, La Monnaie, Nederlandse Reisopera, Opéra de Lyon and Opera North. He has written for The Guardian and The Independent. Documentary work includes BBC Radio 4’s Black Music in Europe 2, presented by Clarke Peters. He currently writes and presents features for BBC Radio 3’s Essential Classics. Peter is a Churchill Fellow, Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, and a Trustee of the Gate Theatre, London.

Peter Brathwaite is a British opera singer. After his degree at Newcastle University he trained at the Royal College of Music, London and Flanders Opera Studio, Belgium. Recent and future engagements include performances with the Royal Opera House, English National Opera, Glyndebourne, La Monnaie, Nederlandse Reisopera, Opéra de Lyon and Opera North. He has written for The Guardian and The Independent. Documentary work includes BBC Radio 4’s Black Music in Europe 2, presented by Clarke Peters. He currently writes and presents features for BBC Radio 3’s Essential Classics. Peter is a Churchill Fellow, Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, and a Trustee of the Gate Theatre, London. Since January 2019, the S

Since January 2019, the S

Anne and William’s wedding was held in March at St. James’s Chapel, which had been richly decorated for the occasion by the celebrated architect and painter William Kent. A contemporary engraving of the ceremony captures the prince and princess with hands clasped in the act of exchanging vows before the Archbishop of Canterbury, while ostentatiously dressed courtiers fill the chapel, gossiping and fanning themselves flirtatiously. [9] The wedding was thoroughly documented in almost every London newspaper, and writers emphasized the size of the crowds at the palace, the rich appearance of the nobility, and the voluntary festivities of London’s citizenry, which included the illumination of the Monument and Ludgate with glass lamps, plentiful bonfires, and fireworks. The Daily Journal published a laboriously detailed narrative of the entire wedding procession to and from the chapel, concluding with a public dinner in the State Ballroom, before the nobility filed through the prince and princess’s bedchamber to view them sitting up in their marriage bed “in rich undress.” The London Evening Post and the Penny London Post offered rambling descriptions of the wedding costumes and other finery observed at court. The bride wore diaphanous “Virgin Robes of Silver Tissue, having a train six Yards long, laced around with a massy Lace, adorn’ed with Fringe and Tassels; on the Sleeves were several Bars of Diamonds of great value; the Habit was likewise enrich’d with several Rows of oriental Pearl.” The women of the beau monde donned “fine laced Heads, dress’d English,” and their dresses featured “treble Ruffles, one tack’d up to their Shifts in quil’d Pleats and two hanging down; the newest fashion’d Silkes were white Paduasoys, with large Flowers of Tulips, Peonies, Emmonies, Carnations, &c. in their proper Colours, some wove in Silk, and some embroidered.” Other papers claimed that the “Embroidery and Beauty” of the princess’s wedding clothes “exceed any thing that has been ever seen here, tho’ all of Manufactures of this Kingdom.” [10] These lengthy and exacting descriptions of fashionable and fine court costume as reproduced in metropolitan newspapers broadcast important political messages. Expensive and newly purchased court attire was used to demonstrate allegiance to the crown and respect for the person of the monarch, while careful accounts of hairstyles, dress cuts, and fabric patterns portrayed the court and royal family as taste leaders who followed fashion trends and encouraged native industry. [11] At the same time, the wedding inspired the production of a whole range of commemorative commercial objects for consumers in Britain and the Netherlands, including medals, highly ornamental engraved paper fans, and enameled porcelain bowls decorated with the portraits of Anne and William, who seem to gaze into each other’s eyes. [12]

Anne and William’s wedding was held in March at St. James’s Chapel, which had been richly decorated for the occasion by the celebrated architect and painter William Kent. A contemporary engraving of the ceremony captures the prince and princess with hands clasped in the act of exchanging vows before the Archbishop of Canterbury, while ostentatiously dressed courtiers fill the chapel, gossiping and fanning themselves flirtatiously. [9] The wedding was thoroughly documented in almost every London newspaper, and writers emphasized the size of the crowds at the palace, the rich appearance of the nobility, and the voluntary festivities of London’s citizenry, which included the illumination of the Monument and Ludgate with glass lamps, plentiful bonfires, and fireworks. The Daily Journal published a laboriously detailed narrative of the entire wedding procession to and from the chapel, concluding with a public dinner in the State Ballroom, before the nobility filed through the prince and princess’s bedchamber to view them sitting up in their marriage bed “in rich undress.” The London Evening Post and the Penny London Post offered rambling descriptions of the wedding costumes and other finery observed at court. The bride wore diaphanous “Virgin Robes of Silver Tissue, having a train six Yards long, laced around with a massy Lace, adorn’ed with Fringe and Tassels; on the Sleeves were several Bars of Diamonds of great value; the Habit was likewise enrich’d with several Rows of oriental Pearl.” The women of the beau monde donned “fine laced Heads, dress’d English,” and their dresses featured “treble Ruffles, one tack’d up to their Shifts in quil’d Pleats and two hanging down; the newest fashion’d Silkes were white Paduasoys, with large Flowers of Tulips, Peonies, Emmonies, Carnations, &c. in their proper Colours, some wove in Silk, and some embroidered.” Other papers claimed that the “Embroidery and Beauty” of the princess’s wedding clothes “exceed any thing that has been ever seen here, tho’ all of Manufactures of this Kingdom.” [10] These lengthy and exacting descriptions of fashionable and fine court costume as reproduced in metropolitan newspapers broadcast important political messages. Expensive and newly purchased court attire was used to demonstrate allegiance to the crown and respect for the person of the monarch, while careful accounts of hairstyles, dress cuts, and fabric patterns portrayed the court and royal family as taste leaders who followed fashion trends and encouraged native industry. [11] At the same time, the wedding inspired the production of a whole range of commemorative commercial objects for consumers in Britain and the Netherlands, including medals, highly ornamental engraved paper fans, and enameled porcelain bowls decorated with the portraits of Anne and William, who seem to gaze into each other’s eyes. [12]

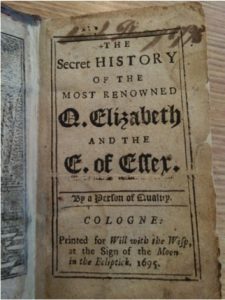

Other secret histories, however, do not fit this pattern: they are not overly partisan and they aim to allow readers access to the affective lives of royal figures even while their narrative structures reinforce the implausibility of their claims. These are the secret histories of Queen Elizabeth–the first, not the second. In 1680 The Secret History of Q. Elizabeth and the E. of Essex was anonymously printed in London, while The Secret History of the Duke of Alancon and Q. Elizabeth was first published in 1691. [3] Both continued to be widely reprinted in cheap editions across the eighteenth century, and the accounts they offered were reimagined in chapbook romances, plays, and operatic songs.

Other secret histories, however, do not fit this pattern: they are not overly partisan and they aim to allow readers access to the affective lives of royal figures even while their narrative structures reinforce the implausibility of their claims. These are the secret histories of Queen Elizabeth–the first, not the second. In 1680 The Secret History of Q. Elizabeth and the E. of Essex was anonymously printed in London, while The Secret History of the Duke of Alancon and Q. Elizabeth was first published in 1691. [3] Both continued to be widely reprinted in cheap editions across the eighteenth century, and the accounts they offered were reimagined in chapbook romances, plays, and operatic songs. Both books call into question the celebrated history of Elizabeth’s reign and her status as an exemplar of Protestant queenship. The Secret History of Elizabeth casts the queen as exceptional but amorous, ruled by her love for Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, reinterpreting his rise, rebellion, and subsequent execution in 1601 as a consequence of the queen’s jealousy and manipulation by courtiers. In The Duke of Alançon, the marriage negotiations that took place between Elizabeth and the French prince in the late 1570s are reimagined to depict the queen as a power-hungry ruler whose love of independence leads her to reject all possible suitors and murder a made-up member of the royal family. Inexpensive and widely available, these stories perhaps invited middling readers to compare themselves favorably to Elizabeth.

Both books call into question the celebrated history of Elizabeth’s reign and her status as an exemplar of Protestant queenship. The Secret History of Elizabeth casts the queen as exceptional but amorous, ruled by her love for Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, reinterpreting his rise, rebellion, and subsequent execution in 1601 as a consequence of the queen’s jealousy and manipulation by courtiers. In The Duke of Alançon, the marriage negotiations that took place between Elizabeth and the French prince in the late 1570s are reimagined to depict the queen as a power-hungry ruler whose love of independence leads her to reject all possible suitors and murder a made-up member of the royal family. Inexpensive and widely available, these stories perhaps invited middling readers to compare themselves favorably to Elizabeth. The 18th-Century Common was developed with substantial support from the Wake Forest University

The 18th-Century Common was developed with substantial support from the Wake Forest University  The Great Forgetting: Women Writers Before Austen

The Great Forgetting: Women Writers Before Austen The Marquis d’Argens (1704-1772) is mainly famous for a book he did not write, Thérèse Philosophe. That is a great pity, as the books he did actually write are far more fascinating and entertaining than that unfortunate misattribution. D’Argens was a sceptic, a thorn in the side of the Catholic Church, whose books were denounced by the Inquisition; one of them, La Philosophie du Bon-Sens, was burnt in Paris. He was also a close friend of Voltaire, and he belonged to the generation that is often overshadowed by that towering genius. Voltaire greatly admired d’Argens’ Lettres Juives, an epistolary work in which he wrote from the point of view of learned Jews discussing and often mocking the beliefs and customs of the Christian world. The book manages to combine the subtly intellectual with the entertaining in a remarkable manner. As a novelist, philosopher, translator, classical scholar, and art critic, d’Argens’ works are so divers that he is difficult to categorize; he was notorious in his own time for his scandalous Memoirs, in which he recalled his youth and love affairs in Paris and Italy in the 1720s and 30s. A wild elopement, a brief army career, and an ongoing battle with his father, who wanted him to study law, provided the main subject-matter. Those who read these Memoirs sometimes formed the opinion that he was merely a libertine and a lightweight, but that is not borne out by a careful study of his work. The mind that emerges from them is deeply reflective, and the philosopher is always apparent in the novels, just as the imagination of a novelist lurks in his works on philosophy.

The Marquis d’Argens (1704-1772) is mainly famous for a book he did not write, Thérèse Philosophe. That is a great pity, as the books he did actually write are far more fascinating and entertaining than that unfortunate misattribution. D’Argens was a sceptic, a thorn in the side of the Catholic Church, whose books were denounced by the Inquisition; one of them, La Philosophie du Bon-Sens, was burnt in Paris. He was also a close friend of Voltaire, and he belonged to the generation that is often overshadowed by that towering genius. Voltaire greatly admired d’Argens’ Lettres Juives, an epistolary work in which he wrote from the point of view of learned Jews discussing and often mocking the beliefs and customs of the Christian world. The book manages to combine the subtly intellectual with the entertaining in a remarkable manner. As a novelist, philosopher, translator, classical scholar, and art critic, d’Argens’ works are so divers that he is difficult to categorize; he was notorious in his own time for his scandalous Memoirs, in which he recalled his youth and love affairs in Paris and Italy in the 1720s and 30s. A wild elopement, a brief army career, and an ongoing battle with his father, who wanted him to study law, provided the main subject-matter. Those who read these Memoirs sometimes formed the opinion that he was merely a libertine and a lightweight, but that is not borne out by a careful study of his work. The mind that emerges from them is deeply reflective, and the philosopher is always apparent in the novels, just as the imagination of a novelist lurks in his works on philosophy.