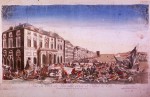

“Vue du Port de Marceille prise de l’Hotel de Ville Dessine du temps de la peste en 1720.” National Library of Medicine.

Disasters permeate the daily news and saturate our consciousness. Hurricane Odile bludgeons Mexico’s Baja peninsula. An Ebola outbreak literally plagues Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone. Ukraine’s eastern regions are torn between Kiev and Moscow. An earthquake rattles Japan’s still-shuttered nuclear plants—and its nervous population. This, as Marie-Hélène Huet notes in The Culture of Disaster (University of Chicago Press, 2012), is the way of the modern world. As she demonstrates in this new, relatively brief, and quick-paced work, what has changed is not the frequency nor the severity of disasters (even if certain kinds, such as nuclear meltdowns, were unimaginable in earlier ages). Rather, what is decidedly modern is our reaction to such events, whether they be human-made or natural. The Culture of Disaster traces not the earth-shattering occurrences themselves but, rather, their aftermaths. The author’s primary concern is thus the experience, rather than the cause, of disaster.

A professor of French at Princeton University, Huet focuses on disasters that either occurred within France or, as in the case of the great Lisbon earthquake of 1755, reverberated within France’s most illustrious circles, primarily during the long eighteenth century. The Lisbon earthquake is often taken as the first great “modern” disaster by historians and eighteenth-century scholars, in part because of the exchange it provoked between Voltaire and Rousseau on the nature of divine providence. Huet argues, however, that we misunderstand why the Lisbon quake opened modernity. It was not important because it inaugurated the rational discourse that would eventually replace fearful reactions governed by religious beliefs or superstition—that trend can be found in earlier periods. Rather, the quake inaugurated the period in which we still live, what we might call the “Long Enlightenment.” Then and now, humans embrace rationality and seek the mastery of the natural world. However, “each natural disaster,” Huet writes, “challenges both the mastery that was our goal and the political system that was put in place to serve such a purpose” (7). The modern world may be disenchanted, but it is still unpredictable and unsafe–as unresponsive to our administrative commands as it was to our prayers.

More frightening even than the Lisbon earthquake were the epidemics that decimated families and destroyed social order, such as the plague that struck Marseilles in 1720. Because the science of disease (its prevention, communication, and treatment) was debated but poorly understood, officials fought over how to police diseased bodies and sick populations. Huet outlines a particularly fascinating clash between those who believed the plague to be an epidemic, spread through the air and thus best avoided by fleeing the city and other susceptible areas, and those who believed it a contagion, requiring its victims to be confined and even condemned to their city block or home in order to limit the disease’s spread. These positions took on liberal and conservative political valences, and Huet draws her reader’s attention to the parallel between this understanding of contagion and later conservatives’ treatment of revolutionary rhetoric as ideas “carried with the speed of winds, spread like thunder and lightning, invading countries, forcibly affecting the people exposed to them – almost subjecting them – to the uncontainable power of new thoughts” (59). This politically informed rhetoric of plague would continue to play out through the cholera epidemics of the nineteenth century in both Europe and the United States.

Central to the culture of disaster that Huet outlines is the increasing interiorization of the catastrophic experience, whereby “the sense of living through disastrous circumstances became interiorized as a unique form of individual destiny” (10). Yet this emphasis on the individual experience of disaster also blurs Huet’s focus, for we tend to believe that we live in world-historical times, and it is only by acknowledging the truth of this ‘fact’ retroactively that the “disastrous circumstances” come to the fore. If the book has a weakness, it is that the disaster topos is occasionally overwhelmed as Huet recounts the details of, for instance, Rousseau’s treatment of negative freedom or Gilbert Romme’s attempts to revise the French calendar and clock. The narratives themselves are so engaging that it can be difficult to see how they connect to Huet’s larger claims about a culture of disaster. These particular cases, grouped with the story of Chateaubriand, sit uneasily in the book’s middle section. Perhaps the argument that “the history of man’s freedom . . . is also one one of disastrous consequences” is simply too complex to be made in a mere fifty pages in which Huet volleys between Rousseau, Kant, Romme, Robespierre, and stoicism (112). Fortunately, The Culture of Disaster quickly regains its focus.

Huet’s treatment of Chateaubriand and the cult of the dead that developed in the wake of the revolution is one of the book’s finest chapters. Though the Victorians’ obsession with death and mourning has been well documented, the post-revolutionary period had its own morbid tendencies. Huet notes in particular the obsession with overflowing graveyards and the burial and reburial of charismatic leaders (133). Chateaubriand, a minor aristocrat who paid his living expenses by selling the rights to his memoirs so that they would be published immediately upon his death, was just the melancholy soul to dwell upon the many tombs to populate his adopted city of Rome. Indeed, he titled his life story Memoirs from Beyond the Tomb. For the conservative loyalist, the execution of Louis XVI meant he would live “through a dead history as a long and fully interiorized disaster” in which the dead continued to speak (145). Chateaubriand’s own disaster was to be more valuable dead than alive and to serve as a voice for a dead political cause for the duration of his life.

The post-mortem life of the dead also characterized one of the most gruesome disasters of the early nineteenth century, the sinking of the Medusa under the command of an incompetent captain. The sinking itself was tragic (and likely avoidable), but what followed was ghoulish: 150 survivors spent two weeks on a rudimentary raft, many dying of dehydration, starvation, or by being crushed under other bodies. Those who did survive to be rescued—a mere fifteen souls—chose to throw the weak overboard and resorted to cannibalism. Five died shortly after their rescue. Using a survivor’s written account, Romantic painter Théodore Géricault produced one of the most powerful and noxious works in the history of art, The Raft of Medusa (Le Radeau de la Méduse). For Huet, the tragedy of the Medusa demonstrates the consequences of the human’s encounter with the inhospitable extremes of the natural world, as do Jules Verne’s novels of polar exploration.

Verne was prompted by Edgar Allan Poe’s tale, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, but perhaps even more so by Captain Sir John Franklin’s lost expedition. (One of Franklin’s two ships was recently discovered on September 7, 2014). Of the 128-man crew, none survived—search parties for Franklin served as the basis for Verne’s own arctic tales. For Huet, Verne’s stories revel in the precarious world of extremes. His emphasis on optical illusions serve to underscore what she perceives as the “fragmenting” effect of disasters, where the senses are unreliable guides to events beyond ordinary comprehension. Yet though we have imperfect tools to do so, Huet persuades us nonetheless that “our culture thinks through disasters” (2). The work of The Culture of Disaster to illuminate “changing conceptual structures” of our disaster-saturated culture suggests both that accounts of modernity’s disenchantment are overstated and that enchantment is perhaps more ominous than generally believed (13).