What would Jane Austen say about Donald Trump? Easy to answer, because she had seen it all before. A Regency girl in a golden age of satire, she attacked the Prince of Wales for his much-lampooned appearance, his lewdness, his licentiousness, his instability, his outrageous spending, his fondness for over-the-top building ventures, his implicit treason, his desire for absolute power, his vanity, his braggadocio, and his love of holidays and sport. Throughout her entire writing career, she kept close watch on the extravagant, dancing prince. At a time when most people were poor, and black lives didn’t matter, she satirized the vulgarian whose wish to become a second Sun King was bringing the country down. In 1813, she would write that she hated him.

Austen was never more than a few degrees of separation away from Prince George. When she was young, he lodged at Kempshot Manor, only three miles from Steventon, and her brother James went hunting with him. At the Wheatsheaf Inn, Basingstoke, where Jane and Cassandra collected the mail, the prince held riotous Hunt Club dinners. As they walked back through those green and leafy lanes, they must have marvelled at the latest excesses of the boorish young man.

At Kempshot, Prince George entertained Mrs. Fitzherbert, and appalled the county with his wild parties; at Kempshot, on honeymoon with Princess Caroline, he reluctantly sired Princess Charlotte. His cohort of “very blackguard companions” were “constantly drunk and filthy, sleeping and snoring in boots on the sofa,” said the Earl of Minto, so that the whole scene “resembled a bad brothel much more than a Palace.” Austen was not prudish, but patriotic, and the prince’s behaviour threatened the nation. She would satirize him through avatars: John Thorpe in Northanger Abbey, Tom Bertram and Henry Crawford in Mansfield Park, Frank Churchill in Emma, and both Sir Walter Elliot and William Walter Elliot in Persuasion.

Like the prince, Thorpe is a “stout young man of middling height,” with a “plain face and ungraceful form.” Like the holiday prince, he lies, boasts, swears, hunts, and talks of nothing but his horses and his rides; like the royal voyeur, he utters “a short decisive sentence of praise or condemnation on the face of every woman they met”; like the prince jeering at his parents, he asks his mother, “where did you get that quiz of a hat, it makes you look like an old witch?” Austen’s lacerating portrait suggests close knowledge of the prince’s vulgar ways.

Even palace insiders said that the heir was unfit to rule. In 1811, just as Austen was revising Pride and Prejudice, he was widely mocked for spraining his ankle while teaching a courtier the Highland Fling. If Austen found that as funny as I do, she may have inserted Mr. Bennet’s exclamation about Mr. Darcy, “For God’s sake, say no more of his partners. Oh! that he had sprained his ancle in the first dance.”

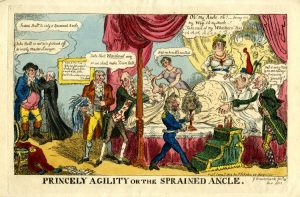

The matter was not trivial. Overweight and overwrought, the regent had gone to bed for ten days. Some said he was avoiding hard political decisions, others that he was going mad like his father. In George Cruikshank’s Princely Agility or the Sprained Ancle (1812), doctors prepare a strait waistcoat; in his Merry Making on the Regents Birthday (August 1812), the regent prances on a petition for the poor. As Austen once wrote, “How much are the Poor to be pitied, & the Rich to be blamed,” and in 1811, at a time of severe economic hardship, he had celebrated the inauguration of his regency in ludicrously opulent style. As Percy Shelley wrote wearily, this entertainment would not be “the last bauble which the nation must buy to amuse this overgrown bantling of Regency.” When the prince became regent, Austen anticipated the king’s death by buying mourning clothes instead.

The prince spent staggering amounts of money on Brighton Pavilion and the Royal Lodge at Windsor. With instability at home and peril abroad, he supported dead Bourbons, hosted exiled French royalty and nobility, bought up their gilded furniture for Carlton House, and planned a second Versailles at Buckingham Palace. Many called his obsession with all things French treasonable; others accused him of coveting the absolute power of Louis XIV, the Sun King.

In newspapers, journals, and cartoons, “the rising sun” went viral as code for the king’s son/sun. Even the title of a scurrilous magazine, The Rising Sun, signalled his obvious impatience for power, and in Persuasion, Charles Musgrove refuses to meet with Sir Walter Elliot’s heir, William Walter, crying out, “Don’t talk to me about heirs and representatives.” As he says to Anne, “I am not one who neglects the reigning power to bow to the rising sun. If I would not go for the sake of your father, I should think it scandalous to go for the sake of his heir.”

Like Thorpe, William Walter resembles the prince, for he is all too keen to claim the titles and privileges he once despised. The sick king was pitied and loved, but not his impatient son. In a bitter jest about her brother James inheriting many beloved possessions before the family left Steventon for Bath, Austen wrote, “My father’s old Ministers are already deserting them to pay their court to his son: the brown Mare, which as well as the black was to devolve on James on our removal, has not had patience to wait for that, & has settled herself even now at Deane.” In Persuasion, Austen would explode the patriarchal hierarchy that privileged her oldest brother and the prince. Snubbed by powerful but ridiculous others, Anne Elliot and Captain Wentworth simply walk away from society’s toxic obsession with “rank, people of rank, and jealousy of rank.”

To judge from Persuasion, Austen was alarmed that the prince, now regent, was spending a large proportion of the national income on high living and ostentatious parade. Beau Brummel had taught him the importance of elegance, just as in Persuasion, “Vanity was the beginning and the end of Sir Walter Elliot’s character; vanity of person and of situation.” Surrounded, like Prince George, by mirrors, he finds it not possible to spend less, “given what Sir Walter Elliott was imperiously called on to do.” His failure to economize gestures to the regent, whose refusal to retrench was threatening the nation.

“Retrench” became another code word for the regent. In Cruikshank’s Economy of 1816, Lord Chancellor Brougham warns him, in an obvious allusion to the French Revolution, “Retrench! Retrench, reflect on the distressed state of your country, & remember the Security of the Throne rests on the happiness of ye People.” In Persuasion, however, Anne and Lady Russell are on “the side of honesty against importance.” To clear Sir Walter’s debts, they urge “a scheme of retrenchment,” and Lady Russell sheets Austen’s satire home by asking, “What will he be doing, in fact, but what very many of our first families have done––or ought to do?”

Personal as well as patriotic reasons fuelled Austen’s loathing of the prince, for he borrowed from the Earl of Moira, who borrowed £6000 from Jane’s brother Henry. Moira defaulted on his debts by becoming Governor-General of India. Thus the regent was partly responsible for Henry’s bankruptcy and consequent heavy losses for other family members, as E. J. Clery explains in Jane Austen: The Banker’s Sister. No wonder that Austen hated him.

In Mansfield Park, Sir Thomas Bertram’s absence in Antigua, like the absence of the sick king, allows his pleasure-loving son to take charge. Like the regent, Tom Bertram wastes both his health and his wealth, and occupies himself mainly with the theatricalities of his position, such as miniature battles in the Serpentine. Henry Crawford provides yet another proxy for the regent, for his “freaks of a cold-blooded vanity” never receive the punishment they deserve, while in Emma, the light-minded Churchill rids himself of his money and his leisure “at the idlest haunts in the kingdom.” The prince’s beloved Brighton, perhaps.

Three days before she died in Winchester on July 17, 1817, Austen wrote an odd little poem about Winchester races. The regent attended them every July. Here St. Swithin accuses “the Lord & the Ladies” all “sattin’d & ermin’d” of being his “rebellious subjects,” rebukes them as “depraved,” and announces that “By vice you’re enslaved/ You have sinn’d & must suffer.” To punish them, he vows to bring down regular rain showers on “these races & revels & dissolute measures/ With which you’re debasing a neighbouring Plain.” It was the satirist’s last fling at a regent who was dissolute, depraved, and a danger to the nation.

Jane Austen’s in-jokes demonstrate her worldliness, her fascination with celebrities, and her relish of rumor. She criticized the Prince of Wales in the only way she could, through her characters and plots. In her resistance to corruption and perversions of power, this savvy, brave, and thoroughly modern woman would have had plenty to say about Mr. Donald Trump.

The Great Forgetting: Women Writers Before Austen

The Great Forgetting: Women Writers Before Austen