Since January 2019, the Scottish Opera has been holding interactive performances of a Jacobite-themed production entitled 1719! in dozens of primary schools across Scotland. The opera addresses the Jacobite wars, in particular, the minor rising of 1719, which the Scottish Opera’s press release calls “a key moment in Scottish history” (“Scottish Opera’s”). Clearly the Scottish Opera chose the 1719 rising as subject matter in part due to its tercentenary, but there is additional significance in reviving this rising as a part of Scottish cultural memory at all, let alone at this exact moment. I argue that 1719! echoes many of the culturally-centered interests of the so-called Jacobite ballads circulating around the time of the rising. Though 1719! does not necessarily draw from such ballads, it demonstrates shared patterns of thought: both 1719! and Jacobite ballads instrumentalize the past to cultivate a unique Scottish identity and sense of a cyclical history that resonates with contemporary cultural and political aspirations.

Since January 2019, the Scottish Opera has been holding interactive performances of a Jacobite-themed production entitled 1719! in dozens of primary schools across Scotland. The opera addresses the Jacobite wars, in particular, the minor rising of 1719, which the Scottish Opera’s press release calls “a key moment in Scottish history” (“Scottish Opera’s”). Clearly the Scottish Opera chose the 1719 rising as subject matter in part due to its tercentenary, but there is additional significance in reviving this rising as a part of Scottish cultural memory at all, let alone at this exact moment. I argue that 1719! echoes many of the culturally-centered interests of the so-called Jacobite ballads circulating around the time of the rising. Though 1719! does not necessarily draw from such ballads, it demonstrates shared patterns of thought: both 1719! and Jacobite ballads instrumentalize the past to cultivate a unique Scottish identity and sense of a cyclical history that resonates with contemporary cultural and political aspirations.

While its more famous predecessor, the Jacobite Rising of 1715, or the Fifteen, was inconclusive on the battlefield in the Battle of Sheriffmuir, the 1719 attempt to restore the Stuart line to the British throne was, for all intents and purposes, a short-lived and failed endeavor. Yet, the rising was unique in terms of its foreign involvement: hoping to “cripple England” or, at least, distract the nation from its mercantile competition with Spain in the Mediterranean (Sinclair-Stevenson 168), Spanish Chief Minister Giulio Alberoni arranged for thousands of Spanish troops to partake in the rising. In reality, only about 300 Spanish forces would arrive in Britain due to poor weather (Worton 115). The small Spanish contingent along with Scottish Jacobites nonetheless undertook the rising and suffered a decisive defeat. 1719! provides an overview of these events and then some, first establishing the rivalry between James Stuart and George of Hanover and then referring to the 1692 Massacre at Glencoe. The opera goes on to offer a rendition of the Battle of Sheriffmuir, which is framed as an attempt by the Jacobites to avenge the massacre. Finally, the opera dramatizes its namesake, drawing particular attention to Spain’s involvement in the rising. It concludes with James’s reference to the birth of Charles Edward Stuart, or Bonnie Prince Charlie, and the promise that, “This is not the end!” (11).

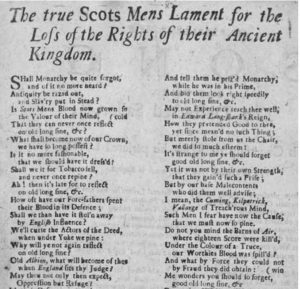

In a sense, eighteenth-century broadside ballads act as analogues to 1719!: though perhaps not direct sources, examination of Jacobite ballads printed around 1719 in relation to 1719! reveals similar cultural and political sentiments articulated by similar methods, namely through a re-imagined Scottish history. To this end, I will first discuss the Jacobite ballad “The True Scots Mens Lament for the Loss of the Rights of their Ancient Kingdom,”[1] written before the 1707 Act of Union between England and Scotland and reprinted in 1718, and its strategic appeal to the past both in its content and in its 1718 re-distribution. I will then proceed to investigate resonances in 1719!

“The True Scots Mens Lament” repudiates the encroaching Act of Union between Scotland and England, shown in lines such as “The Union will thy [Britain’s] Ruine be” (45). While confronting the imminent union, the ballad also speaks both implicitly and explicitly to Jacobitism. In part, it is inevitable that discussion of the union be tied with Jacobitism: after all, the proposal of the union emerged in part as a way for the English government to persuade the “Scottish Parliament to accept the Hanoverian succession, and… stop it backing the Stewarts” (Bambery 55). However, it is the ballad’s recurring appeal to Scotland’s “old long sine” (8), also called “Guid Auld Lang Syne” or “good times long past,” that clearly aligns with Jacobite interests. According to William Donaldson, the concept of Guid Auld Lang Syne—imbued with the “doctrine of the Divine Right of Kings”—served as an “alternative history” for eighteenth-century Scotsmen: “it was made up of a tissue of myth and legend stretching back into the remotest antiquity, and provided a heroic backdrop against which they viewed themselves, a frame for their thinking, and the driving force behind their politics” (5). The use of Scotland’s glorious history in “The True Scots Mens Lament” reflects Donaldson’s assessment: appealing to the past, the ballad functions as an ideological tool for self-identification and, for some, a catalyst for political action.

Besides taking on “old long sine” as its refrain, the ballad reflects this theme in its portrayal of a valorous Scottish history: it memorializes Scottish victories against foes such as Caesar, idealizes heroes who resisted English domination such as William Wallace and Robert the Bruce, and glorifies “our Nation sometime brave, / invincible and stout” (49-50). By establishing a distinctly Scottish history of bravery, pursuit of freedom, and struggle—against England specifically in many cases—the ballad not only fosters a distinctive Scottish identity but one defined by resistance and opposition to England. Furthermore, in chronicling struggle after struggle, “The True Scots Mens Lament” can also been seen as reflecting the “Jacobite commitment to typological/cyclical history” (Harol 55). More than a marker of Scottishness, rebellion appears as a natural and inevitable pattern in Scottish history. The ballad seems to validate the continuance of this cycle. Reflections such as “How oft have our Fore-fathers / spent their Blood in its [Scotland’s] Defence” (17-8) underscore such a reading: the ballad contributes to an imagined Scottish community with shared “Fore-fathers” and a shared history of resistance, which, ostensibly, should be channeled through further struggle against English domination.

The ballad also signals Jacobitical, political concerns by drawing attention to issues of dynastic reign. For example, queries such as “Shall Monarchy be quite forgot” (1) and “What shall become now of our Crown, / we have so long possest?” (9-10) clearly allude to the Stuart line, who had claim to the Scottish—and English—“Crown.” Significantly, no Scottish king reigned since James II’s deposal in 1689, making these questions less relevant to the impending union itself than to the restoration of the Stuart dynasty. Furthermore, the ballad also addresses the Stuart line through its appeal to the “Auld Alliance,” an agreement between France and Scotland in the thirteenth through sixteenth centuries that if one nation had a military dispute with England, the other would engage. After showing dissatisfaction at the encroaching union with England, the ballad entreats, “Why did you thy Union break / thou had of late with France” (105-6). As Murray G. H. Pittock argues, the ballad’s allusion to this alliance “refers to the dream of sixteenth-century Scottish Catholic monarchy: that Mary Stuart, Mary of Guise’s daughter, should be queen (as she briefly was) of France and Scots” (139). Though framed as a nostalgic view of the Scottish past, the ballad is in fact coded with nostalgia for the Stuart dynasty and what could have been. Furthermore, by glorifying Scotland’s relationship with France, a Catholic nation that was currently sheltering the exiled James Francis Edward Stuart and had assisted his father in the Williamite War, the ballad could also covertly show praise for France’s sympathy to the Jacobite cause and express persistent allegiance to the Stuart line. Under the guise of promoting a sense of nostalgia and lament—of remembering “old long sine”—the ballad urges the Scottish people to recognize their historical and cultural difference from England, reaffirm their dynastic allegiance, and, perhaps, perpetuate acts of resistance.

While the content of “The True Scots Mens Lament” demonstrates instrumentalization of the past for cultural and political purposes, its reprinting in Edinburgh in 1718—over a decade after the Act of Union—served a similar aim. In response to the Fifteen and the stirrings of the 1719 rising, government officials cracked down on seditious language: singing or possessing seditious ballads could result in imprisonment and, in rare cases, even execution, though the latter was generally reserved for ballad printers (McDowell 158-159). This compelled ballad-makers to use covert methods to express any Jacobite sentiment. Some ballads such as “The True Lovers Knot Untied” (circa 1687-1732) and “A New Song, Commemorating the Birth Day of her Late Majesty Queen Ann” (circa 1718) portrayed more distant and innocuous members of the Stuart line, such as Lady Arbella and Queen Ann, in a favorable light to show Jacobite allegiance. Another coded strategy was to portray the Jacobite identity and interests “as both de-activated and anachronistic (that is, both passive and in the past)” within ballads (Harol 584). By reviving old Jacobite ballads such as “The True Scots Mens Lament,” ballad distributors and their clientele could not only monopolize on the national consciousness-raising and Jacobitical themes inherent in the ballad, but appeal to contemporary political aspirations with impunity.

Like other Jacobite ballads circulating at this time, “The True Scots Mens Lament” functioned as “an ideological counter-core for those who wished to preserve Scottish cultural and political identity” post-Union (Pittock 134): its redistribution was, in effect, a reassertion of Scotland’s cultural and political difference from England, despite the its lack of governmental representation. Beyond reinforcing a shared Scottish cultural consciousness, however, the ballad’s reprint validated rebellion as an intrinsic, if not necessary, part of Scottish culture.[2] By disseminating a pre-Union ballad that established a trend of Scottish resistance in the aftermath of the Fifteen, ballad-distributors implied that this rebellion offered yet another episode in Scotland’s cyclical history. In other words, it attested to a pattern of struggle in Scotland’s past that continued—and would continue—unabated until the Stuart line was restored and the union with England broken. It also covertly suggested that future rebellions—such as the imminent 1719 rising—were inevitable, if not “providential” (Harol 588).

While “The True Scots Mens Lament” documented, and approbated, a Scottish culture of resistance through historical events, it is worth noting that contemporary ballads likewise reflected the perpetual fight for Scottish liberty through domestic, “individuated” subject matter (Pittock 139). The ballad “A New Song, To the Tune of Lochaber No more” (circa 1723), for instance, features a young man compelled to leave his love and land to fight “Since Honour commands me” (18). Though the ballad does not specify that he fights for the Jacobite cause, for obvious reasons, the fact that its “air at an earlier period is said to have been called ‘King James’s march to Ireland’” implies this (Whitelaw 137).[3] In any case, the lover’s almost natural imperative to fight and his hopeful conclusion, “And if I should luck to come gloriously Hame, / I’ll bring a Heart to thee with Love running o’er, / And then I’ll leave thee and Lochaber no more” (22-4), can be read as mirroring Scotland’s undying hope and unending struggle for liberty.

To return to “The True Scots Mens Lament” not only did the reprint—like many other contemporary works—covertly endorse Scottish resistance, but it also served to reaffirm Scotland’s continental ties and Jacobite allegiance. As stated, the ballad’s nostalgic gesture to the “Auld Alliance” engages in Jacobite coding as well as displays a preference for Scotland’s past alliance with France over a union with England. This reference had further, and slightly altered, significance in 1718. At this time, France’s focus had shifted from its Jacobite sympathies towards a fruitful alliance with England (Worton 31). That being said, the Jacobite cause still had links to France both because of its previous decades of support and the exiled Jacobites that still resided there. While the reference could continue to resonate in terms of Scotland’s connection to France—and in terms of its nostalgia for a shared Catholic sovereign—it could have also resonated with another continental nation: Spain. Though a tiny fraction arrived in Britain due to storms, there were plans for 5,000 Spaniards to take part in the 1719 rising (Sinclair-Stevenson 169). The ballad’s sentiments of idealizing Scotland’s continental relationships—and distancing Scotland from England in the process—would have thus had continued significance, and additional implications, at this time.

Interestingly, despite Britain’s in-roads with France, contemporary anti-Jacobite ballads also aligned these foreign nations with the Jacobite cause. One ballad “A New Song, Concerning Two Games at Cards, Playd Betwixt the King of England, King of France, and Queen of Spain; Shewing the true Honour and Honesty of Old England against the Pretender” (circa 1719), as its title implies, directly links Spain and France with the “Pretender,” or James Francis Edward Stuart. It also specifies “Old England” rather than Britain, purposefully disassociating England from Scotland. Another anti-Jacobite ballad, “A Hymn, to the Victory in Scotland,” similarly creates this division. Describing the 1719 Battle of Glen Shiel as “Battle, sharp and bloody, / Beyond the reach of humane study…‘Gainst study Scots and Spaniards proud” (252), the ballad makes a point of portraying Scotland as in league with Spain. Rather than calling the rebels Jacobites, throughout the ballad they are referred to by their Scottish identities only. Such ballads purposefully highlight the distinction, and opposition, between Scotland and England.

Examination of early-eighteenth-century Jacobite ballads reveals the promotion of a Scottish national consciousness defined by its distinction from England, its association with continental Europe, and its cyclical history of resistance. As suggested, similar patterns of thinking reverberate in the Scottish Opera’s 1719! show. An educational production, the opera teaches primary school students about the Jacobite risings and engages them directly: while members of the Scottish Opera take the larger roles of James Stuart, George of Hanover, and King Phillip of Spain, students sing along as groups of Jacobites, Hanoverians, and Spaniards. Far from a replication of the ballads that circulated around 1719, the opera nonetheless establishes a distinctive Scottish identity and perpetuates the notion of a cyclical Scottish history steeped in adversity and resistance. Coming as it does in the wake of the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, which failed by a small margin, Brexit, which threatens Scotland’s continental relationships, and consequent appeals for another referendum, this cultural cultivation arguably has political resonance.

1719! opens with initial disputes between George of Hanover and James Stuart, during which it establishes the idea of Scotland’s perpetual desire for freedom: “Everybody dreams of a night / When we need no longer to fight / Happy we’d be: blessed and free” (3). Immediately, the opera characterizes Scotland’s history—and, implicitly, Scottishness itself—in terms of rebellion and liberty. The remainder of the opera follows this theme, chronicling cycles of Scottish struggle in the Massacre of Glencoe, the Fifteen, and the 1719 rising. Most likely, 1719! did not directly build off ballad tradition but is influenced by national poets like Robert Burns and Lady Nairne, who themselves “derived one imperative injunction from the Jacobites… to define resistance as the ground of Scottish national consciousness” (McGuirk 253). Nevertheless, in principle, the opera is reminiscent of “The True Scots Mens Lament” both in its memorialization of “old long sine” and its cultivation of a history of rebellion. The opera fosters a unique Scottish identity defined by resistance, which “is related to an entrenched sense of a distinctive national past, buttressed by successive generations of Scottish history writing” (Smith xi).

1719! not only validates this Scottish identity and documents a cyclical Scottish past but implies that Scotland’s “typological or providential history” lives on (Harol 588). This is shown when James Francis Edward Stuart proclaims towards the opera’s end, “now we place our hopes upon this bonnie new prince Charlie” (11). Within the circumstances of the opera, this allusion to the 1745 rising—undertaken by James’s son Charles Edward Stuart—implies that the fight will, must, or is even fated to continue. Perhaps even more interesting in this respect is the opera’s address to its audience:

Is there a just war?

What would you fight for?

Fight if you choose—you might lose.

Hands we extend—friend unto friend

Shall we contend—is this the end? (10)

The opera’s last words provide an answer: “This is not the end!” (11). After establishing an inevitable trend of Scottish resistance, 1719! concludes with the assurance that Scotland’s struggle for liberty will persist. While on one level it does refer to Bonnie Prince Charlie continuing the fight, given the opera’s direct address of its audience and the fact that Charles was obviously unsuccessful, one can assume that 1719! also speaks to current circumstances. Of course, the opera does not advocate violence—a fact underscored by its anxieties over whether “just war” is possible and its peaceful sentiment of “friend unto friend / Hands we extend.” Yet,

in the context of calls for a second referendum on Scottish independence, the opera implies Scotland’s contemporary desire for sovereignty follows a historical pattern or imperative.

The portrayal of foreign involvement in Scottish history also takes on renewed significance in this context. Just as the Jacobite ballad’s reference to the Auld Alliance aligned Scotland with continental nations and established its “antiquity as a nation apart from England” (Ichijo x), 1719!’s depiction of Scotland’s alliance with Spain in the Battle of Glen Shiel works to a similar effect. The opera foregrounds Spain’s participation in the rising. Given that few Spanish forces actually arrived in Scotland to assist in the rising, 1719! is obviously more concerned with the larger implications of the nation’s participation—of its connection to Scotland—than its practical impact.[4] Interest in highlighting this relationship is evident in the opera’s press release when Scottish Opera’s Director of Outreach and Education, Jane Davidson, notes that the Battle of Glen Shiel “is still recalled in the name Sgurr nan Spainteach (The Peak of the Spaniards) in recognition of the Spanish troops who fought there” (“Scottish Opera’s”). While the opera amplifies Scotland’s continental ties with Spain, it distances Scotland from England in the process. True, in 1719!, “England” is only referred to by the Spanish. However, the antagonism of the Hanoverians—seen in proclamations such as “We’ll whack ‘em and crack ‘em till they stop trying / We’ll shoot ‘em and loot ‘em the dead and dying” (9)—clearly magnifies their separation from the Jacobites—who are portrayed as Scottish—and the Spaniards and also pronounces the contrasting unity of the other nations.

Scholars such as Ichijo Atsuko have noted that uses of history in relation to the creation of a separate Scottish Parliament in late-twentieth-century Scotland reveal connections between Scottish “nationalism and European integration” (6). The instrumentalization of history within 1719! arguably demonstrates such connections: in the context of Brexit and renewed appeals for another referendum for Scottish independence, 1719! promotes a uniquely Scottish identity and culture while also foregrounding Scotland’s European associations. In echoing the distinctive national consciousness and unyielding cycle of Scottish resistance imagined by its eighteenth-century analogues, at its most political reading, the opera suggests that a break with the United Kingdom is a necessary, inevitable, and attractive option that would allow Scotland access to its historically-preferred continental ties. While the opera may not necessarily advocate Scotland’s shift away from the United Kingdom and towards the European Union in this manner, it arguably reflects this emerging transition ideologically.

Notes

[1] Going forward, “The True Scots Mens Lament for the Loss of the Rights of their Ancient Kingdom” will be referred to as “The True Scots Mens Lament” in this essay.

[2] Arguably, contemporary ballads regarding individual outlaws such as Rob Roy—who was involved in the Jacobite risings of 1689, 1715, and 1719—worked to a similar effect. For example, in “The Supplication and Lamentation of George Fachney, an Officer in Caldwells Regiment of Robbers, To Rob Roy in the Highlands, with Rob Roys Answer” (circa 1722), Roy is portrayed as engaging in the ‘right kind’ of resistance, breaking the law as a wronged party, not wronging others.

[3] After all, as Murray G. H. Pittock has suggested, “Airs…seem to have been used to indicate Jacobite support within a ballad tradition” (6).

[4] The opera references the storms but does not make clear the extent of their impact on the Spanish troops.

Works Cited

1719! Lyrics by Allan Dunn, music by David Munro, Scottish Opera, 2019, https://www.scottishopera.org.uk/media/3119/1719-lyrics.pdf.

“A New Song, Concerning Two Games at Cards, Playd Betwixt the King of England, King of France, and Queen of Spain; Shewing the True Honour and Honesty of Old England against the Pretender,” circa 1719. British Library – Roxburghe, EBBA 31099. English Broadside Ballad Archive, https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/31099.

Bambery, Chris. A People’s History of Scotland. London: Verso, 2014.

Donaldson, William. The Jacobite Song: Political Myth and National Identity. Aberdeen: Aberdeen UP, 1988.

Harol, Corrinne. “Whig Ballads and the Past Passive Jacobite.” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 35, no. 4, 2012, pp. 581-595.

“A Hymn, to the Victory in Scotland.” The Roxburghe Ballads: Illustrating the Last Years of the Stuarts, edited by J. Woodfall Ebsworth, vol. 8, Hertford, Ballad Society, 1897, pp. 252-253.

Ichijo, Atsuko. Scottish Nationalism and the Idea of Europe: Concepts of Europe and the Nation. London: Routledge, 2004.

McDowell, Paula. “The Manufacture and Lingua-facture of Ballad-Making”: Broadside Ballads in Long Eighteenth-Century Ballad Discourse.” The Eighteenth Century, vol. 47, no. 2/3, Ballads and Songs in the Eighteenth Century, 2006, pp. 151-178.

McGuirk, Carol. “Jacobite History to National Song: Robert Burns and Carolina Oliphant (Baroness Nairne).” The Eighteenth Century, vol. 47 no. 2/3, Ballads and Songs in the Eighteenth Century, 2006, pp. 253-287.

“New Song to the Tune of Lochaber No More,” circa 1723. National Library of Scotland – Rosebery 37, EBBA 34263. English Broadside Ballad Archive, http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/34263.

Pittock, Murray G. H. Poetry and Jacobite Politics in Eighteenth-Century Britain and Ireland. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1994.

“Scottish Opera’s New Primary Schools Show 1719! Commemorates the Jacobite Risings.” Press Release. Scottish Opera, 19 Nov. 2018, https://www.scottishopera.org.uk/press/#scottish-opera-s-new-primary-schools-show-1719-commemorates-the-jacobite-risings-7885.

Sinclair-Stevenson, Christopher. Inglorious Rebellion: The Jacobite Risings of 1708, 1715, and 1719. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1971.

Smith, Anthony D. Foreword. Scottish Nationalism and the Idea of Europe: Concepts of Europe and the Nation. By Atsuko Ichijo. London: Routledge, 2004, pp. ix-xi.

“The Supplication and Lamentation of George Fachney, an Officer in Caldwell’s Regiment of Robbers, To Rob Roy in the Highlands, with Rob Roy’s Answer,” circa 1722. Huntington Library – Miscellaneous 180197, EBBA 32426. English Broadside Ballad Archive, https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/32426.

“The True Scots Mens Lament for the Loss of the Rights of their Ancient Kingdom.” Edinburgh: John Reid in Pearson’s-Closs, 1718. National Library of Scotland – Rosebery 117, EBBA 34350. English Broadside Ballad Archive, https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/34350.

Whitelaw, Alex. The Book of Scottish Song. London: Blackie and Son, 1844.

Worton, Jon. The Battle of Glenshiel – the Jacobite Rising in 1719. Warwick: Helion & Company, 2018.

From a dedicated and, I guess, decent enough scholar to an

From a dedicated and, I guess, decent enough scholar to an

In addition to publishing work on Wycherley, Dryden, Pepys, Cibber, Garrick, and Sheridan, my love of and experiences in the theater demanded that I write into the novel a number of scenes set at the Kings Theatre. Here I was forced to give Tom Killigrew the old heave-ho and replace him with a fictional character involved in the comings and goings of the plots. But actual actors and actresses are mentioned and/or discussed (some substantially) by the characters, as are some forty other historical persons—from Peter Lely and the Duke of York to Queen Catherine and Louise de Kérouaille.

In addition to publishing work on Wycherley, Dryden, Pepys, Cibber, Garrick, and Sheridan, my love of and experiences in the theater demanded that I write into the novel a number of scenes set at the Kings Theatre. Here I was forced to give Tom Killigrew the old heave-ho and replace him with a fictional character involved in the comings and goings of the plots. But actual actors and actresses are mentioned and/or discussed (some substantially) by the characters, as are some forty other historical persons—from Peter Lely and the Duke of York to Queen Catherine and Louise de Kérouaille.

The Hollow Tree is set in New England at the beginning of the Revolutionary War. The rupture in familial and social relationships caused by competing loyalties to the Crown and the nascent United States are depicted through the experiences of Phoebe Olcott, the daughter of a Patriot, who, after his death, goes to live with her Loyalist relatives, the Robinsons, in a small town in Vermont, where the Loyalists are in the minority. Deborah Williams, whose husband, John, is rumored to be fighting on the British side, and her four children are dragged from their house in the early hours of the morning, forced into their oxcart, and sent away with a few possessions; a prized family clock is stolen from the cart. When Deborah protests, “Where will we go? We’ll starve!” the ringleader replies, “Starve if you must…that ain’t no never mind of ourn” (22). Meanwhile, Phoebe learns that her beloved cousin, Gideon, is a spy for the British. The next morning, his body is found hanging from the “Liberty Tree”: “On his shirt a note was pinned. It read ‘Death to all Traitors and Spies’” (32). Her cousin Anne attacks her: “You did this. You and your father and his rebel friends!” (33). Bereft, she visits the place where she, Gideon, and Anne used to meet. Reaching into a hollow tree where they had left messages to each other, she finds a packet “addressed to Brigadier-General Watson Powell, at Fort Ticonderoga.” The packet is wrapped in a paper directing that, should Gideon be captured, it should be delivered to the Mohawk leader, Elias Brant (35-36). The text is in code, but it contains an uncoded request for safe passage for three New York families, the Collivers, the Andersons, and the Morrisays.

The Hollow Tree is set in New England at the beginning of the Revolutionary War. The rupture in familial and social relationships caused by competing loyalties to the Crown and the nascent United States are depicted through the experiences of Phoebe Olcott, the daughter of a Patriot, who, after his death, goes to live with her Loyalist relatives, the Robinsons, in a small town in Vermont, where the Loyalists are in the minority. Deborah Williams, whose husband, John, is rumored to be fighting on the British side, and her four children are dragged from their house in the early hours of the morning, forced into their oxcart, and sent away with a few possessions; a prized family clock is stolen from the cart. When Deborah protests, “Where will we go? We’ll starve!” the ringleader replies, “Starve if you must…that ain’t no never mind of ourn” (22). Meanwhile, Phoebe learns that her beloved cousin, Gideon, is a spy for the British. The next morning, his body is found hanging from the “Liberty Tree”: “On his shirt a note was pinned. It read ‘Death to all Traitors and Spies’” (32). Her cousin Anne attacks her: “You did this. You and your father and his rebel friends!” (33). Bereft, she visits the place where she, Gideon, and Anne used to meet. Reaching into a hollow tree where they had left messages to each other, she finds a packet “addressed to Brigadier-General Watson Powell, at Fort Ticonderoga.” The packet is wrapped in a paper directing that, should Gideon be captured, it should be delivered to the Mohawk leader, Elias Brant (35-36). The text is in code, but it contains an uncoded request for safe passage for three New York families, the Collivers, the Andersons, and the Morrisays. Shadow in Hawthorn Bay pulls together three of the dominant cultures in the settlement of Upper Canada: the First Nations, the Loyalists, and the Scottish immigrants. It takes place in 1815-1816, three years after the War of 1812. In her brief biography, Laura Secord: A Story of Courage, Lunn explains, “Neither the British nor the Americans won the war. The only people who really won were the Canadians. The boundary lines between British North America and the United States remained unchanged” (n.p.). One of the characters in Shadow in Hawthorn Bay, who arrived there as a child, describes it more personally: “Then, when we hadn’t more than just gotten ourselves settled into these backwoods—not quite thirty years later—didn’t those old Yankee neighbours come along and start another war! They thought they’d kick us out of here too. Well, I guess they got a surprise!” (105-106).

Shadow in Hawthorn Bay pulls together three of the dominant cultures in the settlement of Upper Canada: the First Nations, the Loyalists, and the Scottish immigrants. It takes place in 1815-1816, three years after the War of 1812. In her brief biography, Laura Secord: A Story of Courage, Lunn explains, “Neither the British nor the Americans won the war. The only people who really won were the Canadians. The boundary lines between British North America and the United States remained unchanged” (n.p.). One of the characters in Shadow in Hawthorn Bay, who arrived there as a child, describes it more personally: “Then, when we hadn’t more than just gotten ourselves settled into these backwoods—not quite thirty years later—didn’t those old Yankee neighbours come along and start another war! They thought they’d kick us out of here too. Well, I guess they got a surprise!” (105-106).

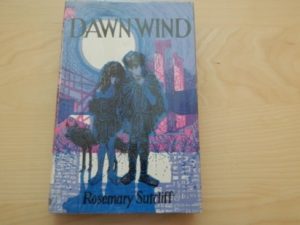

Writing this book was a great pleasure because it allowed me to investigate one of my favorite forms of fiction while employing my scholarly interest in the development of the novel. I realized that I have been reading historical fiction for most of my life; the first playground reading recommendation that I remember was from a classmate who loved Elizabeth Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond. In the young adult fiction section I return to another early love, Rosemary Sutcliff, whose books I first discovered on those magical shelves of books at the back of my elementary and middle school classrooms. The Dawn Wind is the one I remember most clearly from those days; this book allowed me to discover more of her work. The good news is that, even after years of scholarly investigation, I still read historical fiction for pleasure.

Writing this book was a great pleasure because it allowed me to investigate one of my favorite forms of fiction while employing my scholarly interest in the development of the novel. I realized that I have been reading historical fiction for most of my life; the first playground reading recommendation that I remember was from a classmate who loved Elizabeth Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond. In the young adult fiction section I return to another early love, Rosemary Sutcliff, whose books I first discovered on those magical shelves of books at the back of my elementary and middle school classrooms. The Dawn Wind is the one I remember most clearly from those days; this book allowed me to discover more of her work. The good news is that, even after years of scholarly investigation, I still read historical fiction for pleasure. Humanities Viewpoints

Humanities Viewpoints