The Mind Is a Collection is a born-digital museum of early modern cognitive models. For the last decade or so, I have been studying the spaces in which the philosophies of the British Enlightenment were thought, penned, or put into practice. One outcome of this research is a book, The Mind Is a Collection: Case Studies in Eighteenth Century Thought (Penn, 2015). But this book was all along imagined as the catalogue of a museum, a collection of the things that people used to make sense of mental processes. The Mind Is a Collection is that museum, gathering in one place roughly a hundred objects used to model the mind. Some of these objects can be found in private collections or museums around the world, but others have vanished, are fixed in place, or never existed in the first place. In other words, such a virtual space navigates the world in much the same way as an ideal one. It seeks thereby to capture the essential ideality of mind as an emergent property of imaginary objects.

We generally think of the mind as something absolutely different from the rest of the world. There is, on the one side of a bright divide, the world of stuff: intelligible and unintelligible objects, things-in-themselves, perhaps other people, maybe our own bodies. There is, on the other side, the world of the intellect: rational and irrational objects, things as we know them, our sense of others, and some sense of ourselves. This is the bright line of the mind/body divide: there is mind-stuff and matter, consciousness and brute creation. This is what is meant by the catch-all term “dualism.”

The philosophers tell us again and again that dualisms are nonsense–and I’m inclined to agree. There is (they say) no final line in the mind, no screen where ideas pop up or frontier that separates there from here. We are embedded in the world in which we move; “mind” is a category mistake. Yet, there is a catch. Despite the fact that philosophical dualisms have been overwhelmingly, repeatedly, and even routinely discredited, the figures of thought cling on, turning up in philosophy and folk psychology alike. Some of the most powerful voices speaking against these sorts of dualisms have themselves noticed the difficulty of speaking beyond them (see for instance Daniel Dennett, in Consciousness Explained); even if we accept that we are speaking nonsense, it is hard to know how to talk about mental activity without falling back on vocabularies hinging on difference.

The Mind Is a Collection focuses on one dominant instance of this habit, a mainstream cognitive model for the British Enlightenment; it is organized around a related batch of metaphors for mentation, bubbling up repeatedly at the time and place commonly named as the source of modern dualisms. Its crucial intervention is to argue that dualisms name the state of certain forms of networks; it argues that the mind/body distinction, decried as a philosophical fallacy, arises as the proof and function of embedded cognitive systems. Put differently, philosophical dualisms are constructed in working spaces of thought. John Locke calls the mind a cabinet; he was a collector of books. Joseph Addison compares thinking to a walk in a garden; Addison was a planter and an important figure in the development of English gardening. These are metaphors foisted on working spaces of thought.

The usual way to explore this phenomenon would be to write a book about it, posing the argument that “mind” is a name for certain kinds of emplaced relationships. But it seemed just as natural to me to pose this argument through a museum, since collections like museums were the smithies of modern mentation. This, then, is that museum, which contains some of the critical objects of eighteenth-century philosophy. John Locke says that the mind is a cabinet? Well, some of the critical artifacts from his cabinet can be found in the first space of this museum, called “Metaphor.” (The rest can be found in Oxford, at the Bodleian Library.) Joseph Addison compares thinking to walking? The back door of The Mind Is a Collection, located in “Digression,” lets out onto Addison’s favorite walk, the water-walks of Magdalen College. And so on.

Taking these metaphors seriously involves recognizing a reverse vector. We don’t just model our mind on the spaces in which we think. We create gadgets, in turn, based on those mental models. We invent tools that respond to how we understand our minds to work. Call it the feedback loop of cognitive modeling. We are the creatures of our gadgets, just as our gadgets are the creatures thoughts. So, Locke says that the mind is a cabinet, and he becomes a minor pioneer in library science, developing indexing methods based on his library. The pamphlet Locke authored that discusses this method is mentioned in Exhibit 1, “Locke’s Index.” Joseph Addison claims that thinking is like walking, and he becomes a gardener, planting the walks that make his species of thinking possible. The house he built, and walk he planted, is the subject of Exhibit 14, “Addison’s Walk.” We, in other words, shape our environments to match our mental models. This museum collects the traces of this sort of shaping.

Composing The Mind Is a Collection meant producing about 80,000 words of new prose, for the prose of the book is almost completely different than that of the virtual museum. It also meant securing permissions for those handfuls of images not in the public domain—though even the most casual visit to the museum will show you that not many of the images in the museum involve simple photographs of things in the world. Most of what you will find there was painstakingly worked up with architectural modeling software. The process begins with 3-dimensional models built in Sketchup 2015—a museum inspired by multiple iconic C17 and C18 spaces (the old Bodleian, the Ashmolean, Stowe House, and so on), filled with objects modeled from scratch based on my personal viewings of various iconic C17 and C18 objects. I then rendered this space, populated with these things, into photorealistic images, using Thea Render’s engine and studio. Producing these images meant, among other things, developing custom materials, designing virtual “cameras,” and arranging a virtual lighting system. I then cleaned up the resulting images in Photoshop, and built a clickable image map for each. This leads to the final step, when image, image map, and prose are brought together in a single website, hosted by Squarespace. It is here that the virtual museum springs into being. Most of this work I did myself, but some involved work from some very special friends (see for instance Sir Kenelm’s Idea). What results is, I hope, the half compellingly real, half dream-like fantasy of a virtual mind-museum.

Putting together this museum has been a labor of care. But the labor has been about remaining true to the museum’s driving insight: that ideas are things distributed in space. Even a philosophical dualism, so this museum argues, is the name for a certain kind of network—a network that can be seen online. I invite you to visit, to see what I’ve been on about. Admission to The Mind Is a Collection is always free. You’re welcome to browse, to pursue whatever is of interest to you, and to skip what isn’t. Leave for coffee and return. Your ticket is good for multiple entries. The longer, more detailed discussion of anything you find there is available in the book of the same title. Links to places where you can find the book will be found in the gift shop.

As any reader of The 18th-Century Common knows, the last quarter century has witnessed the astonishing digitization of thousands of texts from the past: novels, poems, essays, histories, plays, many of them available for free. For scholars, the creation of this Digital Republic of Learning has (on the whole) been a boon, enabling new modes of inquiry that could barely have been imagined a generation ago. For students, however, the digitization of the archive has been a more mixed blessing. As newcomers to the field, students can very easily find themselves overwhelmed by the sheer abundance of material that shows up in the simple Google search that is likely to be their first means of access. Students are unlikely to know how to judge of the quality or authenticity of what they find, or to be able to recognize the difference between a well-edited text and something with virtually no authority whatsoever. Texts are haphazardly distributed, some behind commercial paywalls such as

As any reader of The 18th-Century Common knows, the last quarter century has witnessed the astonishing digitization of thousands of texts from the past: novels, poems, essays, histories, plays, many of them available for free. For scholars, the creation of this Digital Republic of Learning has (on the whole) been a boon, enabling new modes of inquiry that could barely have been imagined a generation ago. For students, however, the digitization of the archive has been a more mixed blessing. As newcomers to the field, students can very easily find themselves overwhelmed by the sheer abundance of material that shows up in the simple Google search that is likely to be their first means of access. Students are unlikely to know how to judge of the quality or authenticity of what they find, or to be able to recognize the difference between a well-edited text and something with virtually no authority whatsoever. Texts are haphazardly distributed, some behind commercial paywalls such as  Our projects intend to improve the quality of eighteenth-century texts available for students, general readers, and scholars, and to enlist students in the project of producing them.

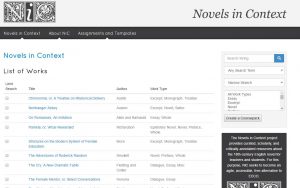

Our projects intend to improve the quality of eighteenth-century texts available for students, general readers, and scholars, and to enlist students in the project of producing them.  Novels in Context

Novels in Context ‘

‘